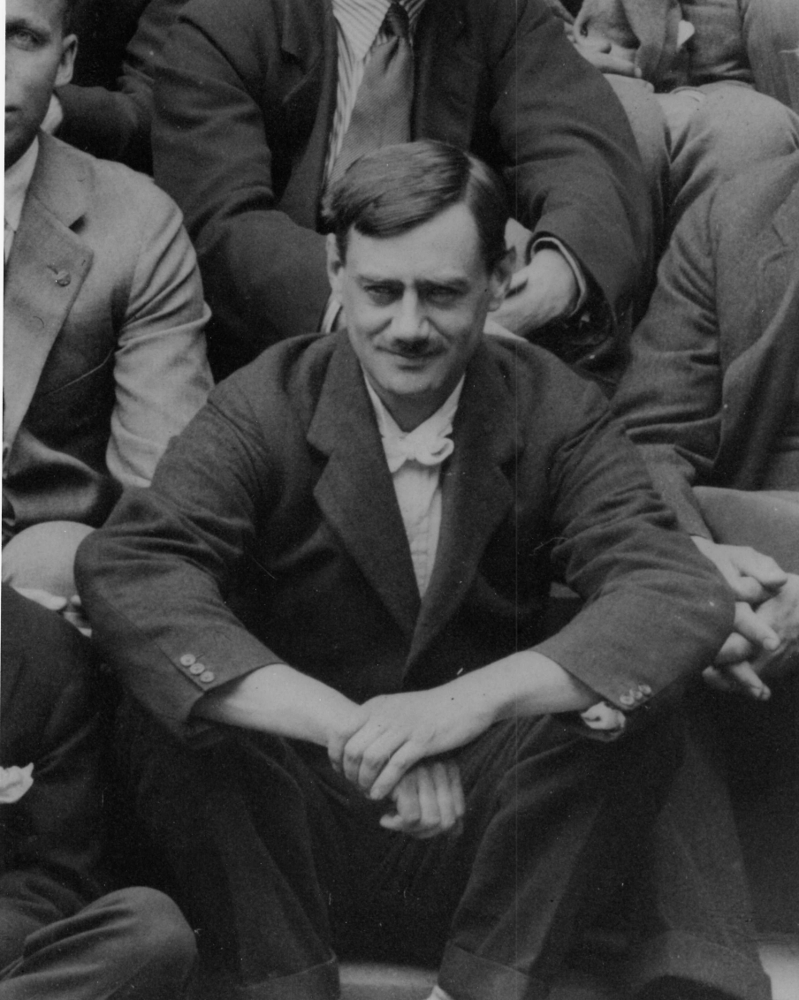

Walter Gill (1883 – 1959) was an Oxford physicist and a specialist in electromagnetic phenomena. He was also a man with an incisive mind – though well-balanced by a ready sense of the absurd. A likely candidate, one would have thought when war broke out in August 1914, for some useful position in the Army then assembling with much urgency. But Gill was too old, so he was told, to be commissioned as an officer and so he took himself to the recruiting office and volunteered as a private.

Following a short spell digging trenches on the Isle of Wight, Gill received a letter from the War Office reconsidering its earlier decision. He was offered a commission in the heavy artillery – his knowledge of trigonometry had clearly helped – and told to report to Woolwich. But the arsenal had no guns so, to keep its newly-created officers busy, they were lectured on the art of grooming horses, incessantly. During the time he spent there, much of which involved such seemingly pointless activities, the not-so-young Second Lieutenant Gill became acquainted with many strange military practices not least of which was the need to salute almost anything that moved.

But the war was itself moving on and soon it was realised that there was need for officers well-versed in the wireless art and especially its use for intelligence purposes. Gill was immediately transferred to the Royal Engineers in whose parish wireless had found itself. This appealed to him for many and obvious reasons: his physics background equipped him rather better than most for such a technical task and his natural scepticism, when confronted by extravagant claims, made him the ideal intelligence analyst.

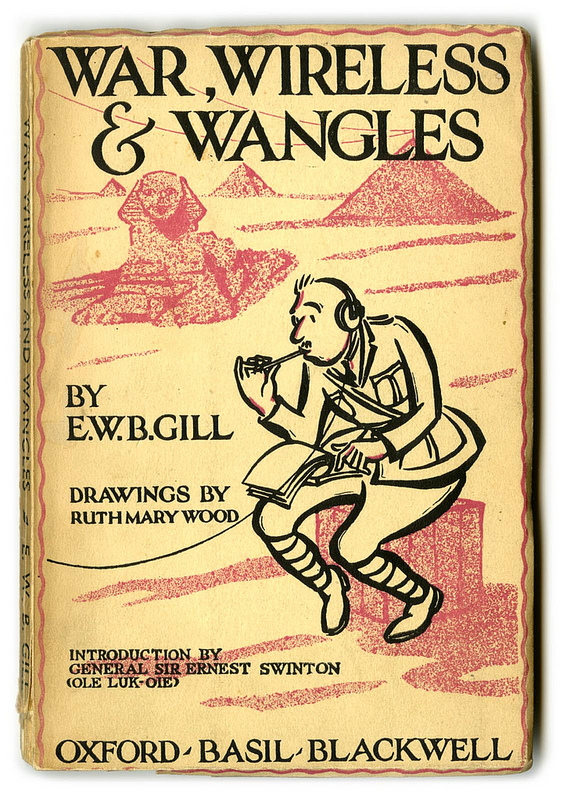

After the war, in 1934 in fact, Gill published a delightful book describing his wartime experiences. Called War, Wireless and Wangles, and illustrated with some wonderful cartoons, the book recounted, in often hilarious detail, the contest between the “Teutonic mind”, as he saw the German obsession with organisation of the most methodical and precise kind and the, at times, almost shambolic British response. As just one example, he described how the Zeppelins, those cumbersome predecessors of the bombers of the next war, were all equipped with wireless and each had a call sign beginning, shall we say, with the letter L followed by another, thus LA, LB, LC and so on. It took little intelligence, in both senses of the word, on the British side to soon deduce that this grouping of letters was reserved for the German Zeppelin fleet and, from that, considerable operational advantage flowed. Some time later, realising this weakness in their system, the German planners changed their call signs but, in well ordered fashion, so LA became MB and so on. More was to follow.

Every hour, and almost on the hour, those Zeppelins would report their position to the High Seas Fleet under whose command they fell. These regular wireless transmissions were a bonanza of the highest order for the listening British wireless stations with their associated direction-finding facilities. Not only was warning given of an impending attack, several hours before they crossed the British coast, but their positions and courses were plotted as they lumbered on.

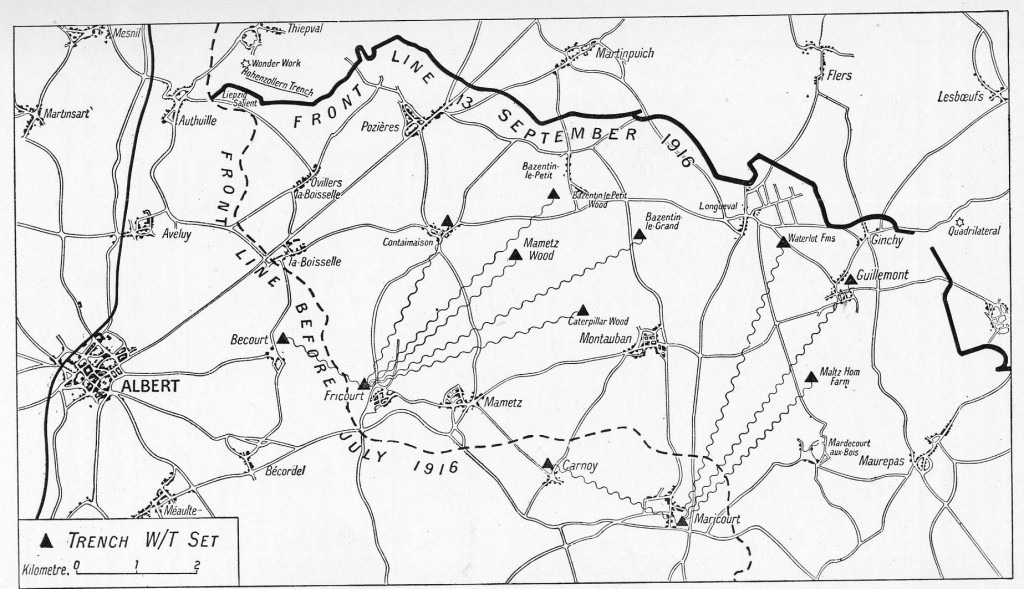

But behind the humour was much of historical value too, particularly of a technical nature. The art of direction finding by radio came into its own during the war owing to the work of two brilliant engineers at the Marconi Company: H.J. Round and C.S. Franklin. By means of the infant valve technology of the time that provided unprecedented amplification, and arrays of antennas that produced controlled directivity, these two men gave the Army a formidable intelligence tool. But it was the Royal Navy, initially highly sceptical until they changed their view on seeing the performance of that equipment when deployed in France, that took great advantage of the technology. In May 1916, a 1.5 degree shift in a DF bearing indicated that the German High Seas Fleet was on the move from its anchorage at Wilhelmshaven and this intelligence enabled the Navy to position its Grand Fleet for the Battle of Jutland that took place the next day.

Gill himself was soon on his way to Egypt. He was posted to what would become a wireless intercept station but his first task was to assemble another one on Cyprus so he proceeded thither with the four tall masts of a Bellini-Tosi DF antenna. That they fell down during the erection process was merely part of the Army’s day but all was soon well once the guys had been correctly set. By now Gill had become something of an antenna expert and his next contribution followed in short order. Back in Egypt and charged with setting up another intercept station he astounded his commanding officer when he announced that he’d found the ideal very tall supporting structure for its aerial. Since nature had provided nothing taller than palm trees in the region, the CO was naturally sceptical until Gill pointed out the Great Pyramid at Giza with a wire affixed to its pinnacle. This aerial proved itself to be very effective: a Zeppelin, on its mission over England, was heard on the single-valve receiver of the station. No mean feat!

After encounters with Egyptian princes and British Army officers who kept pet chameleons, Gill began to acclimatise to the rather exotic way of life common, or so it seemed, at the eastern end of the Mediterranean. From Cyprus he went to Salonika to take charge of one of the intelligence wireless stations in that region. This was the place, it was alleged, that St Paul only visited once. Afterwards he contented himself by writing epistles to its inhabitants. It turned out that malaria was rife in the country and, as might be expected, the Army took this very seriously. Various deterrents were either to be swallowed or applied as medical science evolved. One day he noted that the latest approved substance bore an uncanny resemblance to gearbox grease. It was claimed to be lethal to mosquitoes. However, Gill was confronted by the regimental sergeant major just before he was due to order all his men apply the stuff to themselves. Should he first remove the mosquitoes from the tin where they appeared to be eating the grease?

By the war’s end, the now Major Gill had become one of the British Army’s experts in the art of wireless intelligence both technically and operationally. The latter skill he acquired without benefit of formal instruction. When in Egypt, and the flow of intercepted German wireless traffic became a daily occurrence, the standard procedure was to send it all, by cable, to London where it would be deciphered by experts, perhaps at “Room 40” the centre where such dark arts were practised. But to a man of Gill’s intelligence and curiosity, and with the collaboration of a similarly endowed colleague, it seemed only natural to “have a go” themselves. And soon, based on little more than common sense plus the application of a logical mind, they did indeed “crack” the code. It should be said at this stage that it was by no means a high-grade cipher; more like something based on a “child’s first cipher-book”, as Gill put it. German cipher policy, it would seem, differentiated between theatres of war and clearly the further east those happened to be the lower the quality of the cipher required.

They duly sent the deciphered ciphers to London in the approved way and fully expected to be soundly reprimanded for their unauthorised efforts. However, the reaction forthcoming was precisely the opposite: their action was approved and the War Office said they would send one of their experts to Egypt to give Gill and his colleague instruction in the latest cipher-solving devices. This story has interesting repercussions soon after the outbreak of the next World War when, once again, Gill offered his services to the military. And again he found himself at the very sharp end of the intelligence war. However, this time, his indiscretion by once again breaking the German code (emanating from the Abwehr no less) had a very different outcome. That story, though, has been told elsewhere and will not intrude upon this account of his First World War service.

Walter Gill’s war ended in 1918 with him back in England and in command of the Army’s intelligence wireless stations as well as a training school. For his service he was awarded the OBE (mil.) and was twice mentioned in despatches. One of Gill’s many remarkable characteristics was his modesty. He sought no honour for himself nor even any publicity. Finding a single photograph of the man proved a major task and when accomplished it shows Walter Gill, back at Merton College, Oxford, in 1922 where he resumed his academic career until the next encounter with the Germans when he again offered his services.

This blog post is based on Dr Austin’s full-length article on EWB Gill published in The Journal of the Royal Signals Institution vol.29, No.2, Winter 2010 [pdf].

About the author

Dr Brian Austin is a retired engineering academic from the University of Liverpool’s Department of Electrical Engineering and Electronics. Before that he spent some years on the academic staff of his alma mater, the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa. He also had a spell, a decade in fact, in industry where he led the team that developed an underground radio system for use in South Africa’s very deep gold mines.

He also has a great interest in the history of his subject and especially the military applications of radio and electronics. This has seen him publish a number of articles on topics from the first use of wireless in warfare during the Boer War (1899 – 1902) and South Africa’s wartime radar in WW2, to others dealing with the communications problems during the Battle of Arnhem and, most recently, on wireless in the trenches in WW1. He is also the author of the biography of Sir Basil Schonland, the South African pioneer in the study of lightning, scientific adviser to Field Marshall Mongomery’s 21 Army Group and director of the Atomic Energy Research Establishment at Harwell.

Brian Austin lives on the Wirral.