By Elizabeth Bruton

Update on 23/03/15: Hippisley Hut is now available for sale via Bedfords & Co at http://www.bedfords.co.uk/SearchPropertyDetails.aspx?propid=35329_BUR130028 and in the meantime is available to rent as a holiday home at http://www.kettcountrycottages.co.uk/cottage/hippisley-hut/

Update on 29/07/14: Much thanks to Brian Austin for clarifying the details of Richard L. Hippisley and Richard John Bayntun Hippisley; the article has now been amended accordingly.

Hippisley Hut, Hunstanton, as it looks today. Image courtesy of Sowerby’s.

Hippisley Hut in Hunstanton, Norfolk is now up for sale by Sowerby’s. This ordinary wooden house near Hunstanton on the Norfolk coast is of historic interest being the birthplace of wireless interception during World War One. So who was Hippisley and what was his role in development of wireless interception during World War One? Why did he choose Hunstanton for his wireless interception “hut”?

Hippisley’s background and role in wireless interception at the outbreak of war

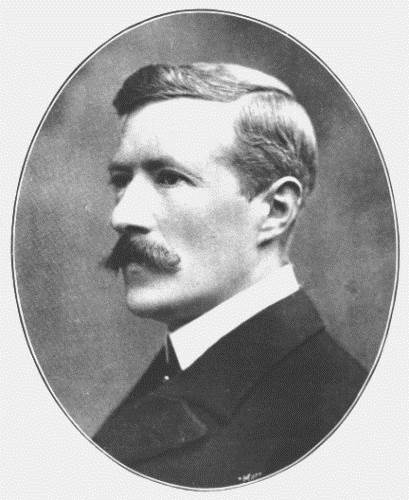

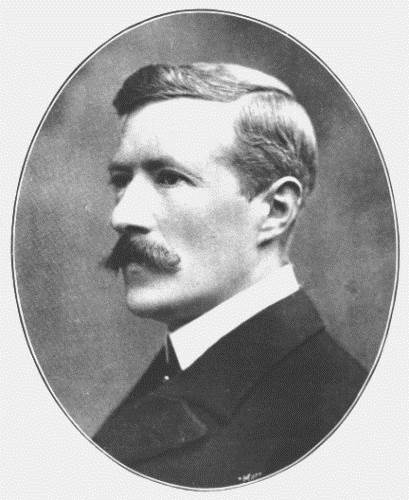

Richard John Bayntun Hippisley (1865-1956). Image from Mate’s County Series (1908) and available in the public domain.

Richard John Bayntun Hippisley (1865-1956) (known as Bayntun and referred to as such throughout this article) was born in Somerset in 1865 and was educated and trained in electrical and mechanical engineering: he was trained at Hammond College (later Faraday House), London and apprenticed at Thorn Engineering Company. In July 1888, Bayntun was gazetted as a 2nd Lieutenant in the North Somerset Yeomanry.

Bayntun Hippisley’s interest in science and technology was very much following in a family tradition. His grandfather, known as the “Old Squire”, was a member of many of Europe’s leading scientific societies and a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS), and Bayntun inherited this interest in science. Bayntun Hippisley’s specific interest in electrical engineering and telecommunications may have been sparked by the earlier work of a relative (a half-Uncle, by my reckoning), Richard Lionel (R.L.) Hippisley (1853-1936). R.L. Hippisley was a member of the Royal Engineers and served as Director of Telegraphs in South Africa during the Second Boer War (1899-1902). In 1902, Colonel Hippisley returned to England and served as Chief Engineer (Scottish Command) of the Royal Engineers until 1910 when he retired. In 1903, Colonel Hippisley wrote History of Telegraph Operations during the South African War, 1899 – 1902 and in 1903 and 1906 he served as one of the British representatives at the International Conferences on Wireless Telegraphy held in Berlin.

In 1908, Bayntun followed his elder relative’s path in the armed services, becoming an honorary Lieutenant Colonel of the North Somerset Yeomanry. It was also around this time, and possibly due to his relative’s interest in wireless telegraphy, that Bayntun too began to develop an interest in wireless. Soon Bayntun acquired a wireless license from the Post Office to operate his own wireless station, operating under the callsign HLX (later 2CW). In 1912, he operated a wireless station in the Lizard, Cornwall and picked up messages from the Titanic. In 1913, Hippisley was appointed a member of the War Office Committee on Wireless Telegraphy.

At the outbreak of war, many pre-war wireless amateurs including Bayntun approached the Admiralty about setting up a network of wireless stations to intercept enemy wireless traffic. Lacking the resources and manpower to establish this network themselves, the Admiralty gladly accepted and many pre-war wireless amateurs became naval “voluntary interceptors”.

Two of these wireless amateurs who joined up had already been logging intercepts of German traffic at their amateur stations in London and Wales respectively, despite the official call to confiscate all privately-owned wireless receivers. These two men were friends and wireless amateurs Edward Russell Clarke, (callsign THX) a barrister and automotive pioneer, and Bayntun Hippisley.

From their wireless stations in Wales and London respectively, Bayntun and Russell Clarke were receiving German naval signals from the German Navy on a lower wavelength than was currently being received by the existing Marconi stations. They had isolated and reported a number of regular signals they believed to be from German naval wireless stations at Neumunster and Norddeich. Their report was passed onto the Admiralty’s Intelligence Division and so, along with many other such amateurs, they were sent to work for Naval Intelligence as ‘voluntary interceptors’ (VIs) and reported their signals intelligence back to Room 40. Bayntun was appointed Commander RNVR for service with the Naval Intelligence Division.

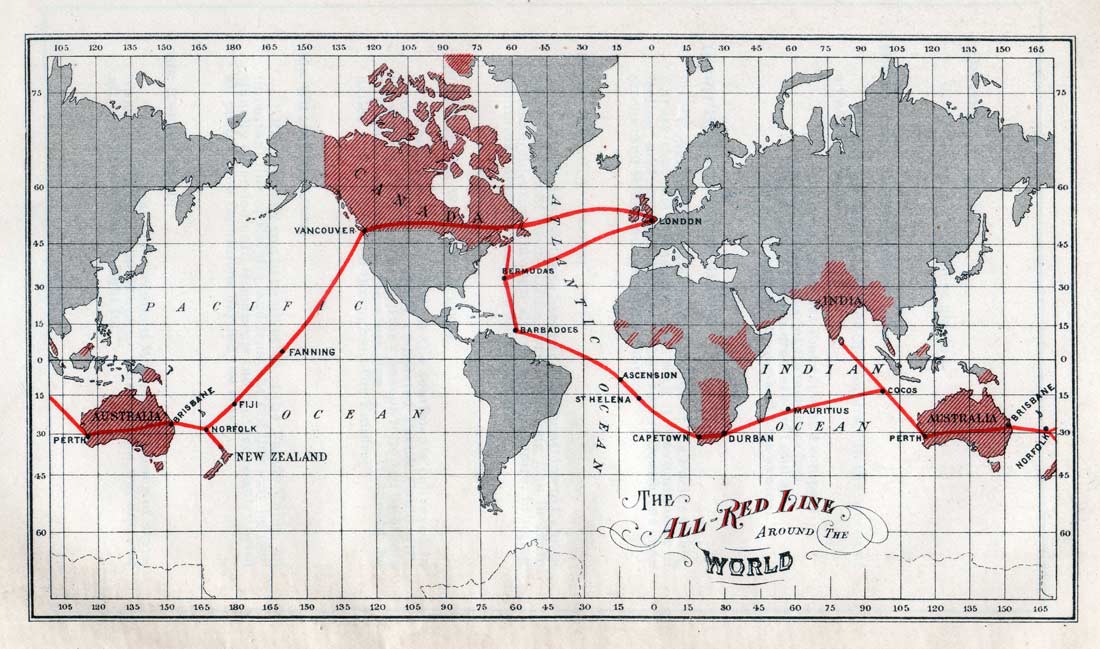

In late 1914, Bayntun and Russell Clarke were sent to Hunstanton on the Norfolk coast to setup a listening post in a former coastguard station in what became known as ‘Hippisley’s Hut’. Hunstanton was chosen because it was the highest point nearest the German coast and was also home to an existing Marconi wireless station.

Marconi wireless station at Hunstanton

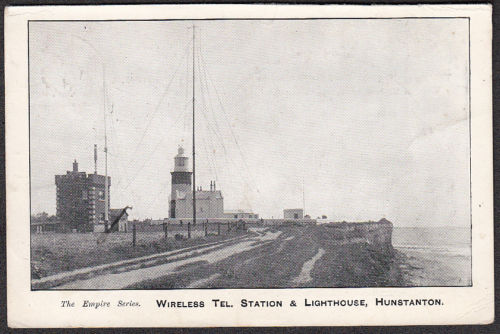

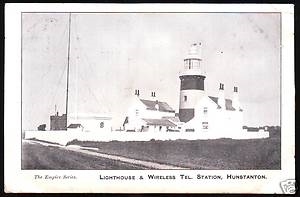

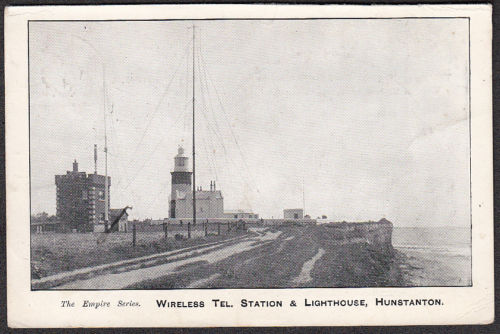

The Marconi wireless station at Hunstanton was established about 1909 and the former power station is still in place today.

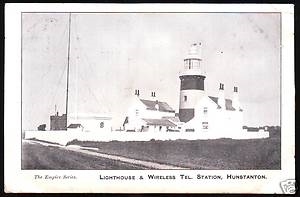

“The Empire Series”: Lighthouse & Wireless Telegraph Station Hunstanton postcard, c. 1909. Image courtesy of Gavin Fuller.

“The Empire Series”: Lighthouse & Wireless Telegraph Station Hunstanton postcard, c. 1909.

Two of the contemporary images of the Marconi wireless station at Hunstanton come from the Empire series. The “Empire Series” (or sometimes “E.S.”) was published by the Pictorial Post Card Company which operated from Red Lion Square, London between 1904 and 1909. They also printed view-cards, novelty cards, actors and actresses, and comic cards by Donald McGill as well as the Empire Series postcards.

Wireless interception at Hunstanton

When Bayntun and Russell Clarke arrived at the coastguard station at Hunstanton in late 1914, they found a wooden mast with no aerial but they were soon intercepting signals. The station was very successful, intercepting German naval and airship wireless signals, and led to a series of 14 wireless intercept (Y stations) being setup along the British coast as well as station in Italy and Malta.

As a result of his wartime service and successes, Bayntun was awarded an OBE (military) in 1918; this was promoted to a CBE (civil) in 1937.

Wireless Direction-Finding Station on the cliffs near Hunstanton, c. 1915.

Image available in the public domain.

Hunstanton was also home, at least temporarily, to a wireless direction-finding station (B station) which was used to locate the position of German naval vessels and airships by triangulating their wireless signals.

Utilising this combination of signal interception and direction-finding, the resulting intelligence came to the fore in 1916 with notable successes during the First Blitz by Zeppelins and the Battle of Jutland. By 1917 a turning point had been reached with more U-boats sunk and Zeppelins downed than any previous years mostly in thanks to wireless interception and decryption. Wireless was also successfully employed with the clearing of the Western Approaches in late 1917, a development which was credit to Bayntun himself. By 1918 the Admiralty signals intelligence (or ‘SIGINT’) guaranteed complete control of the airwaves and during the first four months of the year four Zeppelins were shot down over England and twenty-four U-boats sunk.

After the war

After the war, Bayntun returned to his family’s estate Ston Easton in Somerset and resumed his pre-war life. In 1931 he was elected a County Alderman for Somerset, and appointed Traffic Commissioner for the Western Counties. He was awarded the CBE (Civil) in 1937. Bayntun died in April 1956 at the age of 90 and his life was remembered with an obituary in the Journal of the Institution of Electrical Engineers as well as letter in The Times from his friend Lieutenant-Colonel H.W. Kettlewell. Kettlewell’s letter in The Times praised Bayntun as “an almost unique personality … [who possessed] a most remarkable mechnical and scientific gift…” In particular, Kettlewell highlighted Bayntun’s contribution to the war effort during the First World War:

[Bayntun was] given carte blanche to select, organize and maintain throughout the war the wireless stations round these [British] isles; so secret and of such importance was his work that he could then only be communicated with through the Admiralty. Some 20 years or more I happened to meet a well-known admiral, who, when I mentioned Bayntun Hippisley as among my friends, remarked: “He was one of the men who really won the war.”

Bayntun Hippisley’s vital role in World War One was further highlighted in a 1995 article in The Times by William Rees-Mogg, “Tradition and the innovate talent”:

In Somerset we believe that Bayntun Hippisley personally won the First World War. He came from a family with an engineering and scientific talent; his grandfather had been a Fellow of the Royal Society. Bayntun was an early pioneer of radio research; in 1913 he was appointed a member of the Parliamentary Commission of Wireless for the Army . When war broke out in 1914 he joined Naval Intelligence and was made a commander. He was the man who solved the problem of listening to U-boats when they were talking to each on the radio by devising a double-tuning device which simultaneously identified the waveband and precise wavelength. That, it is said, was essential to clearing the Western Approaches in late 1917, when American troops were coming over. Bayntun Hippisley sat in Goonhilly listening to the U-boat captains as they chatted happily to each other in clear German; he told the destroyers where to find them; the food and the Americans got through.

Sources and further information

A Brief History of the Hippisley Family by Mike Matthews

Auto Biography & History Michael John Hippisley Born 18th July 1934

Grace’s Guide: Baynton_Hippisley

h2g2: Richard John Bayntun Hippisley (1865-1956)

JHRB, Obituary: Richard John Bayntun Hippisley in Journal of the Institution of Electrical Engineers, Vol 3 No 26 (1957), 111.

Kettlewell, Lieutenant-Colonel H.W. Cmdr. R. J. B. Hippisley. The Times, 11 April 1956, p13.

Rees-Mogg, William. Tradition and the innovative talent. The Times, 5 June 1995, p5.

West, Nigel. GCHQ: The Secret Wireless War, 1900-86. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1986, 33, 54.

About the author: Dr Elizabeth Bruton is postdoctoral researcher for “Innovating in Combat”. See her Academia.edu profile for further details.