By Elizabeth Bruton

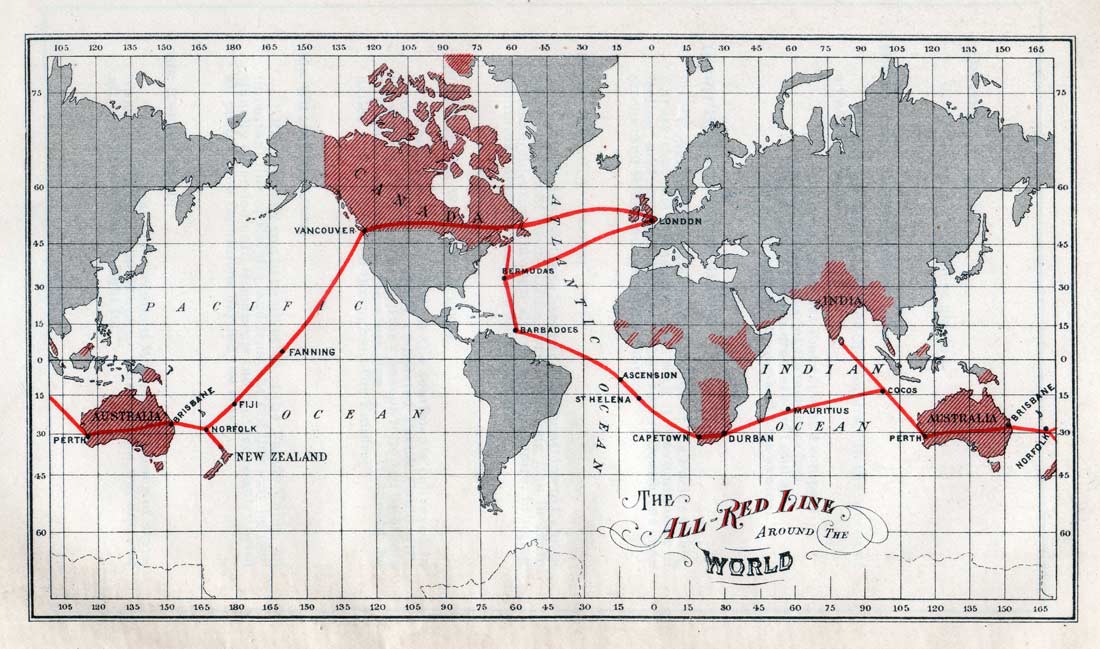

1902 British All Red Line map, from Johnson’s The All Red Line – The Annals and Aims of the Pacific Cable Project (1903). Image available in the public domain.

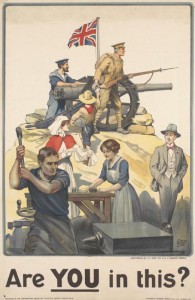

In a previous article, we’ve discussed German cable telegraphy in World War One, and now it is time to examine British cable telegraphy in the conflict. Much, if not all, British long-distance telecommunication relied on the “All-Red Line”, the network of British-controlled and operated electric telegraph cables stretching around the globe and so called due to the colour red (or sometimes pink) being used to designate British territories and colonies in the atlases of the period.

The origins and early history of the “All-Red Line”

The “All-Red Line” was operated through a mixture of public and private enterprise with the Eastern Telegraph Company (ETC) operating many of the telegraph cables in Asia, Africa, and beyond. By the late nineteenth century, telegraphy cables from Britain stretched to all corners of the globe forming a massive international communications network of around 100,000 miles of undersea cables.

News which had previously taken up to six months to reach distant parts of the world could now be relayed in a matter of hours. In 1902 the “All Red Line” route was completed with the final stages of constuction of the trans-Pacific route and connected all parts of the British empire.

This telegraph network consisted of a series of cable links across the Pacific Ocean, connecting New Zealand and Australia with Vancouver and through the Trans-Canada and Atlantic lines to Europe. Submarine telegraph cables remained the only fast means of international communication for 75 years until the development of wireless telegraphy at the end of the nineteenth century.

Security and telegraph cables

Security and reliability were an important part of this vast international telecommunications network: there were multiple redundancies so that even if one cable was cut, a message could be sent through many other routes, operating a bit like the modern day Internet (which actually has far more redundancies built in). Further security was added in the location of telegraph line landfall: the “All-Red Line” was designed to only made landfall in British colonies or British-controlled territories although this may have compromised on occasionally.

In 1902 and around the time that the All-Red Line was completed, the Committee of Imperial Defence was established by the then British Prime Minister Arthur Balfour and was made responsible for research and some coordination of British military strategy. In 1911 and with the possibility of a war in Europe looming, the committee analysed the All-Red Line and concluded that it would be essentially impossible for Britain to be isolated from her telegraph network due to the redundancy built into the network: 49 cables would need to be cut for Britain to be cut off, 15 for Canada, and 5 for South Africa. Further to this, Britain and British telegraph companies owned and controlled most of the apparatus needed to cut or repair telegraph cables and also had a superior navy to control the seas.

British telegraph cables at the outbreak of war

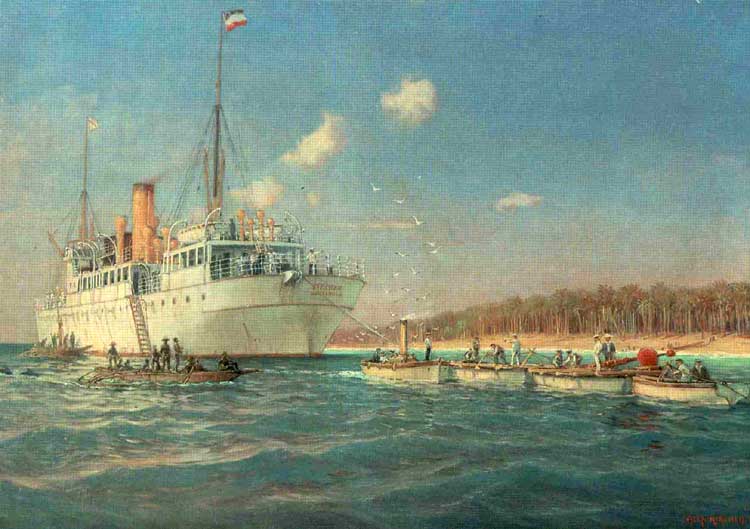

As a resullt, when war broke out in August 1914 and some isolated telegraph stations such as the one at Cocos Islands asked for further security and military protection due to the risk of German attack, they got none and were left to their own devices in terms of protection. Some of the staff on the Cocos Island station constructed a fake telegraph cable and this was one that was cut by the Germans in their attack on the island in November 1914 and so telegraph communication via this telegraph station was able to continue.

Indeed, as a result of the redundancies built into the system and British naval superiority, the “All-Red Line” – a network which was strategically important to businesses, government, and military and a keystone in British imperial activities – remained robust, secure, and essentially uninterrupted for the duration of the war.

Sources and further information

A Short History of Submarine Cables

Johnson, George. The All Red Line; the annals and aims of the Pacific Cable project. Ottowa: James Hope & Sons, 1903. Available via Internet Archive.

Kenndy, P.M. Imperial Cable Communications and Strategy, 1870-1914, The English Historical Review, Vol. 86, No. 341 (Oct, 1971), pp. 728-752. Available via JSTOR.

About the author: Dr Elizabeth Bruton is postdoctoral researcher for “Innovating in Combat”. See her Academia.edu profile for further details.