Camille Leadbetter tells the story of her first encounter with the portrait of Sir John Chardin, currently hanging at the top of the stairs in the History of Science Museum in Oxford.

Hello! My name is Camille and I’m a History of Art Undergraduate at the University of Oxford.

Since the start of 2020, I have been researching the provenance and connotations of the portrait of Sir John Chardin that is currently placed at the top of the stairs in the History of Science Museum.

In this blog series, I will guide you through the process of my research and present you with the tools to reimagine this portrait and what it means in the contemporary age.

I will also encourage you to develop and share your own thoughts about the portrait.

I hope you enjoy!

My first encounter with Chardin

I first came across this portrait during a trip to the History of Science Museum in Oxford with my cohort in the History of Art department.

It did not strike me as a particularly stunning or well executed work of art but its dominant positioning and frame demanded my attention as I ascended the stairs to the second floor of the museum.

The eccentric frame that accompanies the portrait, complete with astronomical and navigational devices and spherical globe on the top, is carved in wood and painted bronze.

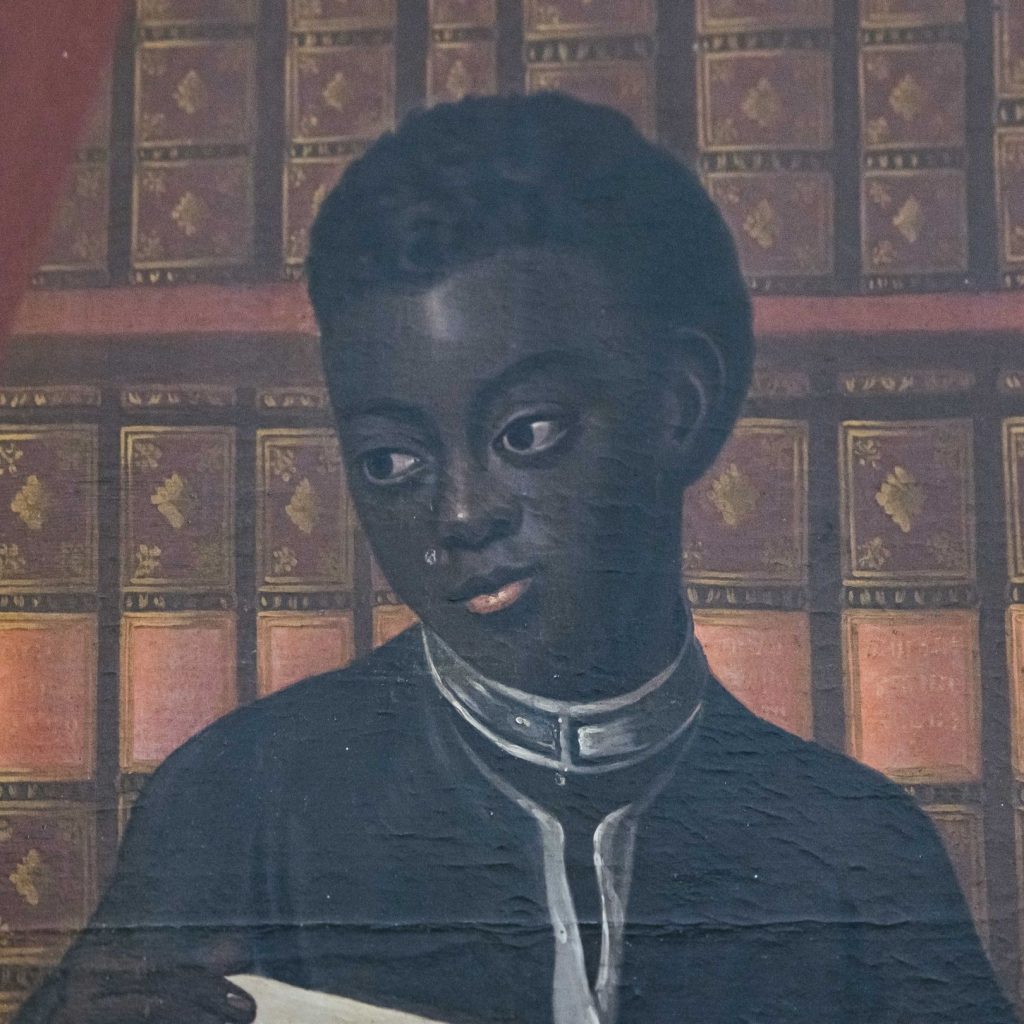

I did not recognise the man in the portrait, seated and staring out towards his audience with confidence, nor did I recognise the young black boy standing meekly behind him and holding up a 17th century map of the Middle East to which the seated figure points.

There is no reference to the boy in the accompanying label.

The Museum as a frame

As part of my Art History degree, I have studied the concept of the museum being as much a frame of an image as its physical frame. The art historian Paul Duro established that the positioning and whereabouts of a painting hold ‘institutional, ideological and perceptual’ connotations, all of which contribute to how a work of art is received by its viewer.

Therefore, the museum and what it chooses to display can often have underlying effects on how its core values are characterised in the public eye.

Especially for a museum not specialising in art, choosing to show this as one of the only paintings on display to the public could be misleading about its curatorial mission.

This project has involved giving the boy the thought and consideration he has not been afforded in the past — which is all the more crucial now in an age when the traditional museum role of gathering and displaying collections to be consumed and interpreted by viewers and conservators is now being reframed in the light of an evolving relationship between the institution and the contemporary public.

Camille Leadbetter is a History of Art student at the University of Oxford.

Other posts in this series:

Beginning the Process of Decolonising the History of Science Museum’s Collection