Reframing the “Chardin” portrait

Researching the provenance of this portrait and its frame in the museums across Oxford

Camille Leadbetter continues her investigation of the Chardin portrait, and shares her quest to bring the story of the young boy — and thousands like him — into the foreground.

The issue of negative representations of minority ethnic figures is especially poignant at this time, with the recent protests for the Black Lives Matter movement, and the issues surrounding the statue of Cecil Rhodes in Oxford.

Perhaps in light of these current events, now is an apt time to think about the images we have on portraits and those we have on display in public places — measuring with contemporary eyes whether they are still appropriate and the sort of attitudes they are promoting.

Bringing the boy into the foreground

When I started my research on the portrait of Sir John Chardin, I had two clear missions.

The first was to identify why Chardin’s portrait was chosen to be on display in the History of Science Museum.

The second was to distinguish the boy in the background and try to find out who he might have been.

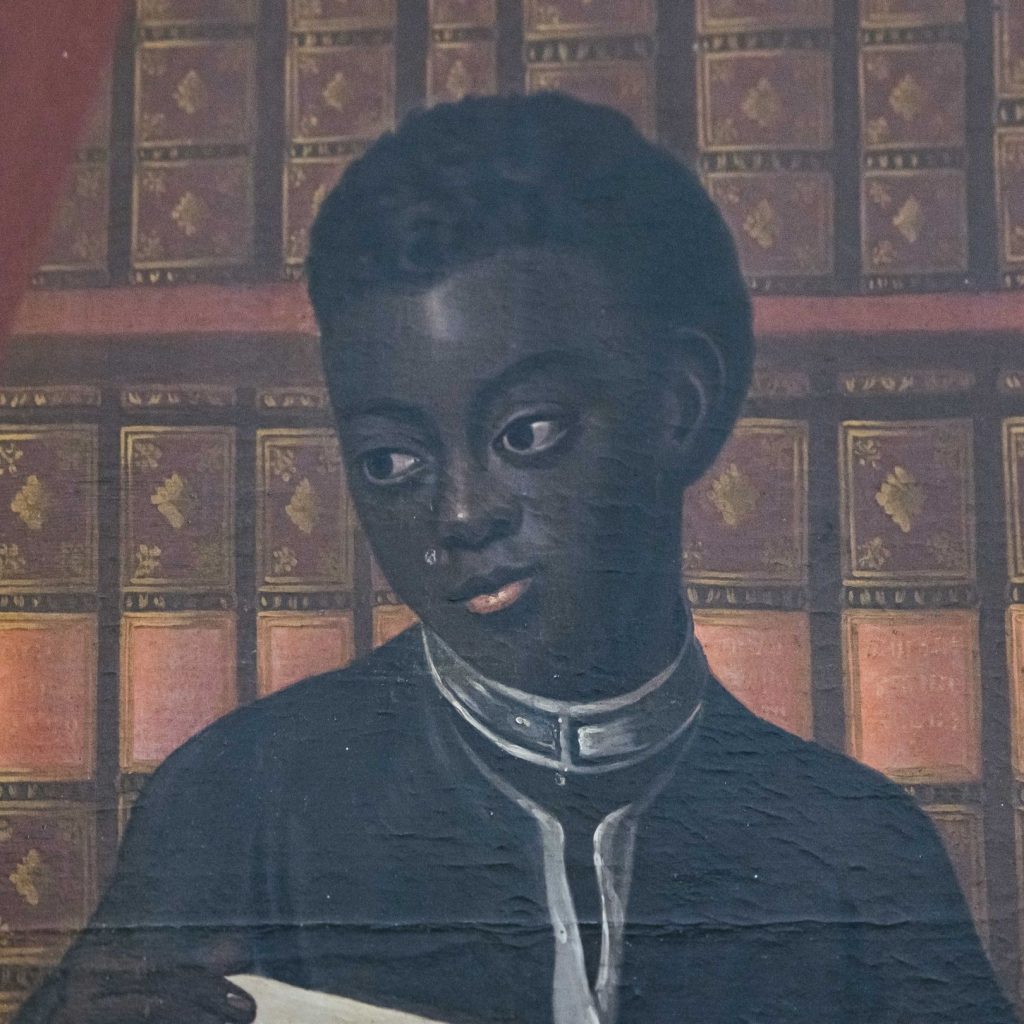

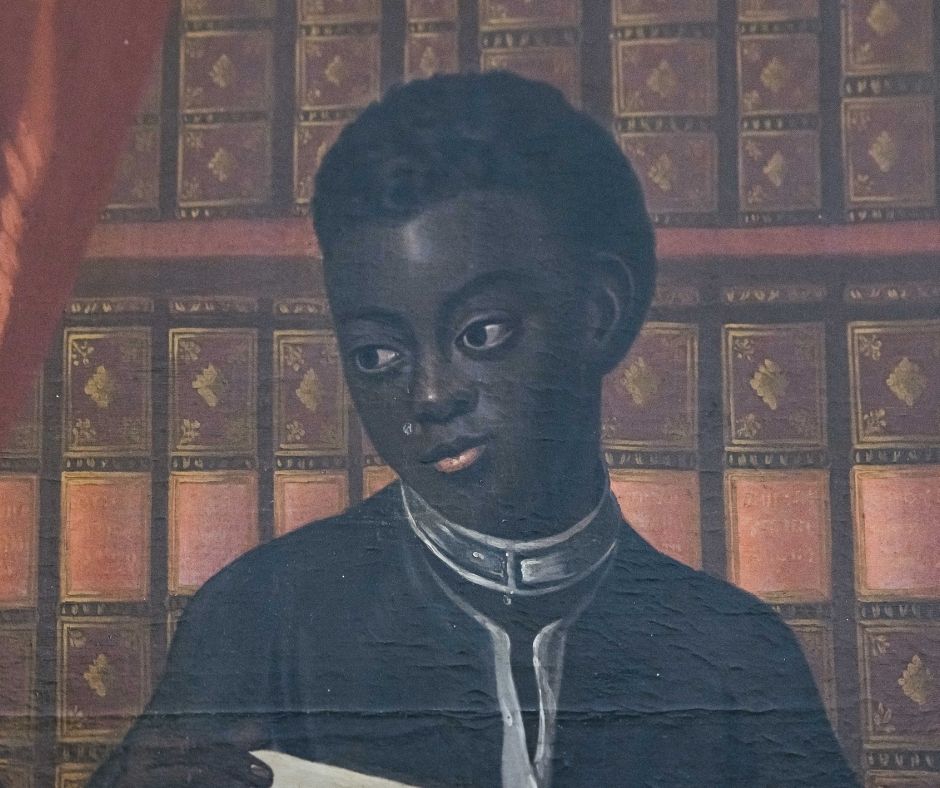

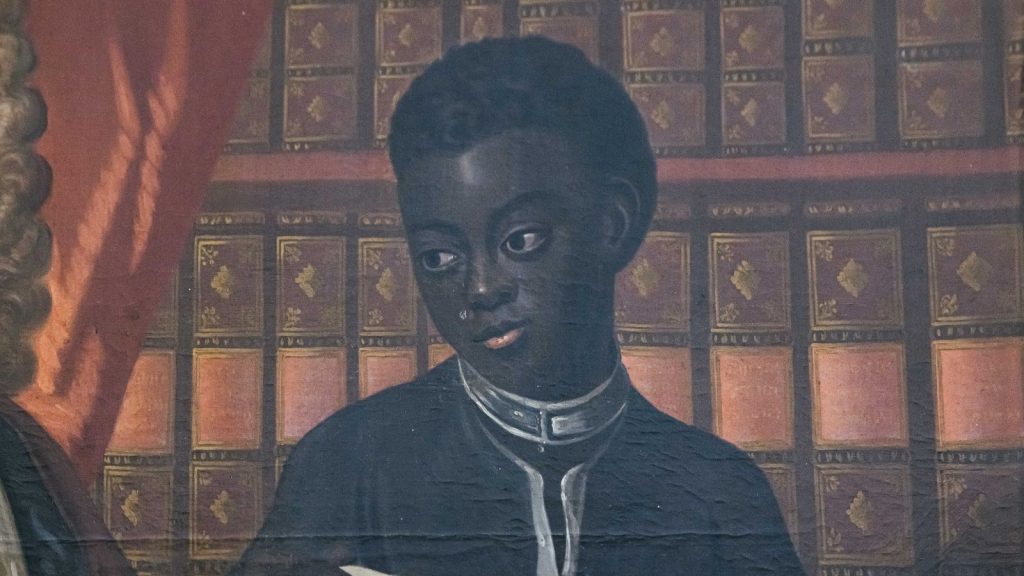

In the portrait, Chardin is staring out at the viewer with a confident, enigmatic smile. He looks reputable and intelligent, and perhaps this is why his portrait has been undisputed in the museum setting for so long.

Meanwhile, the young boy has a metal cuff around his neck and is depicted gazing downwards, as though in shame or perhaps to show that he is in awe of Chardin.

The label accompanying the painting did not reference the boy and I wondered whether this representation of a slave should gather more attention.

Indeed, it seems troubling to have this image on public display in the contemporary age.

I couldn’t help wondering what this portrait could potentially communicate to someone seeing it on display in the museum. And furthermore could it convey and identify a certain set of undesirable values to the museum?

I knew that I wanted to find out more about this portrait and find out why exactly it had been chosen by the museum to be placed at the top of the stairs — in the direct eyeline of everyone ascending to the second floor collections.

I began my journey of tracing the provenance of the portrait — and identified a series of questions that I wanted answers to.

Who was Sir John Chardin?

Firstly, I wanted to figure out what exactly was Chardin’s connection to the History of Science Museum?

To me, Chardin was not an instantly recognisable figure to many and I struggled to recall any connection between him and any particular scientific endeavours or innovations.

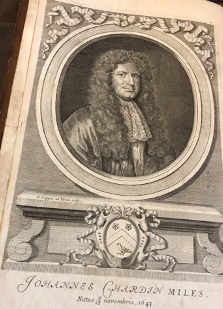

The label in the HSM had already informed me that Sir John Chardin (16 November 1643 – 5 January 1713) was a French Huguenot refugee, jeweller, traveller, diarist, and agent of the Dutch East India Company.

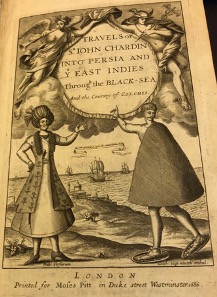

Picture of Sir John Chardin from

The Travels of Sir John Chardin into Persia

and the East Indies: the first volume,

containing the author’s voyage from Paris to Isfahan

He was also chief jeweller to Shah Abbas II of Persia, some of whose astrolabes are held in the museum.

Finding the original portrait

Some initial online research brought me to the National Portrait Gallery’s (NPG) website, which had a file on the Portrait of Sir John Chardin.

To my surprise, I discovered that the portrait in the History of Science Museum (HSM) is actually a copy, and that the NPG archives hold the original portrait of Chardin.

Here, I also discovered that the copy in the HSM is on loan from the Ashmolean, who acquired it from the Bodleian.

This further brings attention to my earlier question; why has the painting been chosen and why in that particular spot?

The quality of the painting is noticeably not high, yet it is framed and positioned as though it is an immensely powerful piece of high art.

Further reading

I also found these online sources particularly useful for my research:

- One of Chardin’s most notable travel journals is titled of A Journey to Persia: Jean Chardin’s portrait of a Seventeenth Century Empire (of which the Oriental Institute library in Oxford has a copy).

- Another useful record of his travels is The Travels of Sir John Chardin into Persia and the East Indies: the first volume, containing the author’s voyage from Paris to Isfahan (an original seventeenth-century copy of which is held in the Christ Church library’s special collections).

- The NPG website listed Later Stuart Portraits 1685-1714 by John Ingamells as further reading surrounding the portrait. I was able to access it from the Sackler Library in Oxford.

This book is a record of various influential seventeenth-century gentlemen and their portraits. I found that the original portrait once belonged to the Grenville Family and was sold by Christies in 1977 as Portrait of a Gentleman, possibly of the Grenville family and so was assumed to be of another sitter.

- Also, a fictive narrative has been written by the author Danielle Digne based around the life of Sir John Chardin entitled Le Joaillier d’Ispahan (The Jeweller of Isfahan).

Searching the archives

I contacted the National Portrait Gallery and arranged a visit to their archives (this was scheduled for April 2020 but unfortunately due to the Covid-19 pandemic was not able to go ahead).

As the copy was gifted by the Ashmolean, I thought the next place to look should be the Ashmolean archives, so I contacted them and arranged to visit the Western Art Print Room on 19th February 2020.

The Ashmolean had a number of useful documents and files on the portrait. I found that the portrait of Chardin held in the History of Science Museum is attributed to the artist Bartholomew Dandridge. I also found that another copy was made and is held in the Rosenbach Museum in Philadelphia, USA.

Before the copy was gifted to the History of Science Museum by the Ashmolean, it belonged to the Bodleian library in Oxford. It came to be in the Bodleian, it is suspected, after being gifted by Chardin’s eldest son in 1746. It was transferred to the History of Science museum in 1951.

This is an interesting topic for further research, as the motives for the erection of this portrait at this time are unknown to me, and not easily deciphered by the portrait itself or its frame.

Image from The Travels of Sir John Chardin

into Persia and the East Indies: the first volume,

containing the author’s voyage from Paris to Isfahan

In addition, I am intrigued that the decision to place this colonial portrait in the gallery was made within the last 70 years.

The visible and the invisible in Dandridge’s painting

As my quest to find out more about the young child in the painting seemed to be coming to few solid conclusions, I decided to research more on the broader topic of black figures in eighteenth century European artworks.

I visited the British Baroque exhibition at Tate Britain to examine their method of representing portraits with colonial underpinnings and those which featured representations of slaves.

Studying the labels used to accompany these portraits, I found that they included posters warning people before entering that the exhibition contained images of slaves. I wondered whether the History of Science Museum would benefit from altering its label to be more transparent about the colonial underpinnings of this work of art.

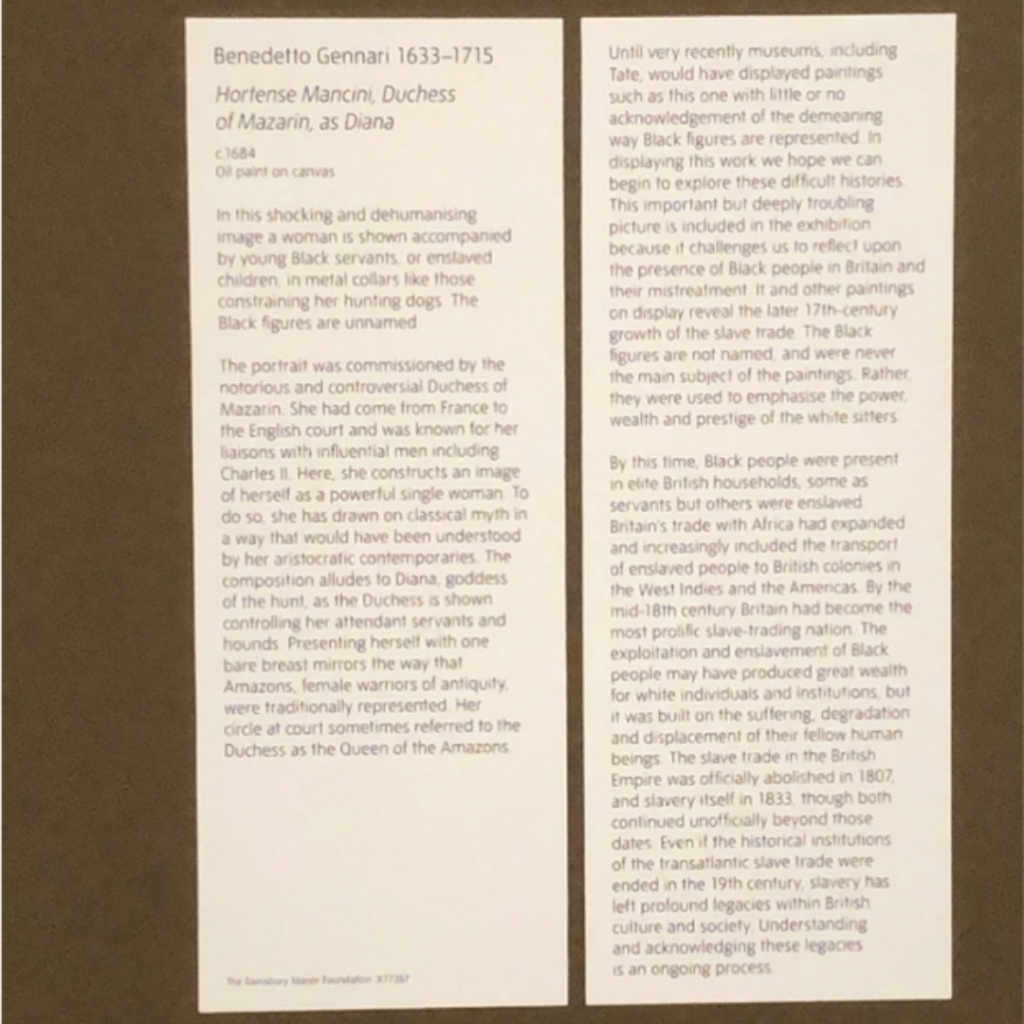

A particular painting which stood out to me in this exhibition was ‘Hortense Mancini, Duchess of Mazarin, as Diana’ (1684) by Benedetto Gennari.

This painting features a wealthy and prominent white woman, surrounding by young black children, who seem to be positioned in the same manner as dogs or creatures who, in the period, were seen as lower than humans (of course, white humans).

Interestingly, the plaque accompanying this piece actually condemns the depictions of the black figures as ‘shocking and dehumanising’.

This acknowledgement of these representations as negative demonstrates the desire of the gallery to approach the tricky and unfortunate depictions of black figures in historical art.

Portrait of Hortense Mancini, Duchess of Mazarin, as Diana (c. 1688) by Benedetto Gennari

I asked myself, ‘Is this the way forward for historical artworks depicting these slave figures?’.

Some useful books and articles on the black figure in historical art

- The article Finding Context for a 17th-Century Enslaved Servant in a Painting by Largillierre from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

I found it interesting to read about how the writer was captured by the figure of the black boy in a painting by Largillierre and inspired to explore his background. The research undertaken by the author of the article seemed close my own.

The conclusions in the article were that the boy’s presence serves to add metaphorical connotations to the white female sitter and the artist essentially used him to compliment her.

- The article Invisibility Speaks: Servants and Portraits in Early Modern Visual Culture by Peter Erickson.

Here, Erickson regards the tendency to invisibility of the black figure in art.

They are so often depicted in background or subservient positions to a supposedly more important ‘main’ sitter, just as the young boy in Dandridge’s piece stands behind Chardin, carrying out a service to him and staring at him — as we as an audience are also guided to do.

Seeing the lost faces in European art

Erickson’s work particularly stood out to me as he implied that a lot of European artworks from around this period employed the black or ‘ethnic’ figure as a symbol of the exotic, or to emphasise how culturally knowledgeable and well-travelled the main sitter is. In Chardin’s case, based off his career, this may well be the case.

All these interesting finds about depictions of black people in historical art made me all the more determined to find out who the boy in the portrait was, and why he was there. I felt disheartened to think he could be a fictive instrument employed by the artist to serve Chardin’s appearance.

The Art Historian Shearer West has stated that portraits and their frames often enclose ‘timeless values and heritage’. By this, she is suggesting that they often subliminally present ideologies on behalf of whoever erected them and those who position them in certain areas.

Therefore we cannot ignore the potential of this portrait for inflicting messages steeped in prejudice on its viewers. To explore and fully address these broader racial matters, we must reconsider the role of this boy.

Bringing the boy to the foreground

Although it has been hard to trace him, we can do better by him at least by reframing how we interpret this portrait. We can choose not to overlook his presence and instead see him as a representative of all those forced into servitude before and after the seventeenth century. Although their voices have been lost and quietened for so long, they have a chance to be heard (and seen) now. We can show our allegiance by bringing this boy from the background, to the foreground of our mind’s eye.

In my next Blog, I explore how I opened up the issues surrounding this portrait to the public.

Camille Leadbetter is a History of Art student at the University of Oxford.

Other posts in this series:

Beginning the Process of Decolonising the History of Science Museum’s Collection