The class gain hands-on experience of history with replica Galilean telescopes.

Guest post by Dr Michael Bycroft, whose University of Warwick undergraduate history class visited the Museum for an afternoon of talks and hands-on experience with instruments of the 17th and 18th centuries.

**

As every historian of 18th-century experimental philosophy knows, lectures and instruments are an excellent couple. It’s all very well to hold forth in front of a powerpoint presentation, but there’s nothing like a real-life orrery or electric machine to pull in the punters. It was with this philosophy in mind that I approached the curators at MHS about the possibility of putting on some rational entertainment for the second-year undergraduates who are taking my 20-lecture course on early modern science (get in quick! only 7 lectures left this year! free with a £9000 subscription to the University of Warwick!).

Unlike figures from the period such as Francis Hauksbee and Benjamin Martin, I do not make my own scientific instruments and have no shop in which to demonstrate them. However I did have the help of two MHS curators (Stephen Johnston and Sophie Waring), and this turned out to be more than enough. With a bit of information from me about the content of the lectures, including an outrageously ambitious list of desiderata, they put together a 3-hour programme of displays and demonstrations that worked in its own right and yet tied in nicely with the course.

Beginning the visit

Assistant Keeper Dr Stephen Johnston invites the students to handle and use instruments of navigation and astronomy.

The visit began on a Monday afternoon at 2:30pm, with the drawing of the chunky steampunk lock that sits on the front door of the Museum and that is on its own worth the trip to Oxford. The students were handed an A4 piece of paper with the programme on one side and a list of essay questions cunningly printed on the other. Thanks to the flexibility of the curators, the visit was timed to coincide not only with two lectures on experimental philosophy and natural history, but also with the publication of the list of questions that students will answer in their next two assignments.

We began in the Entrance Gallery with two pairs of armillary spheres, showing both the ancient Ptolemaic theory of the universe, with a stationary earth at the centre, and the Copernican, with the earth a planet orbiting a central sun. Some were complete spheres and some were cut away to more clearly reveal the position of the planets — a nice illustration of the pedagogical power of inanimate objects. A nearby set of telescopes and microscopes gave us a chance to reflect on different kinds of instrument — the mathematical, the optical, and even the philosophical. A microscope with its own specimen slides, little pieces of pre-packaged nature, was an introduction to science as a commodity.

More object lessons awaited us in the basement. The students knew from one of the lectures that the Museum building contained a chemical laboratory as well as a natural history collection when it opened in 1683, and that the first curator, Robert Plot, used the laboratory to search for the universal solvent (and also, presumably, an indestructible vessel to hold it in). A display of 17th-century chemical vessels brought this story to life. So did Stephen’s description of the encrustations of 17th-century soot discovered in the ceiling of the room during renovations in the years around 2000. There was a labelled skull alongside the vessels. It reminded us that this was once an anatomy theatre as well as a chemical laboratory and a school of natural history. Three domains of nature, all being taught in a university building in the 17th century — clearly there was more to early modern science than the Academies and Societies we have heard about in the lectures!

Spreading 18th century science

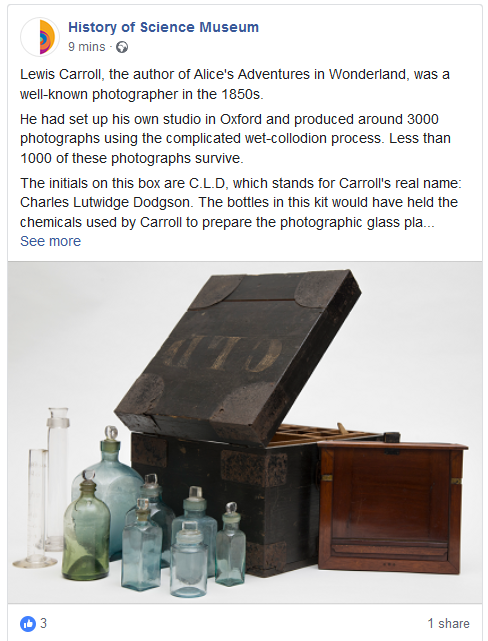

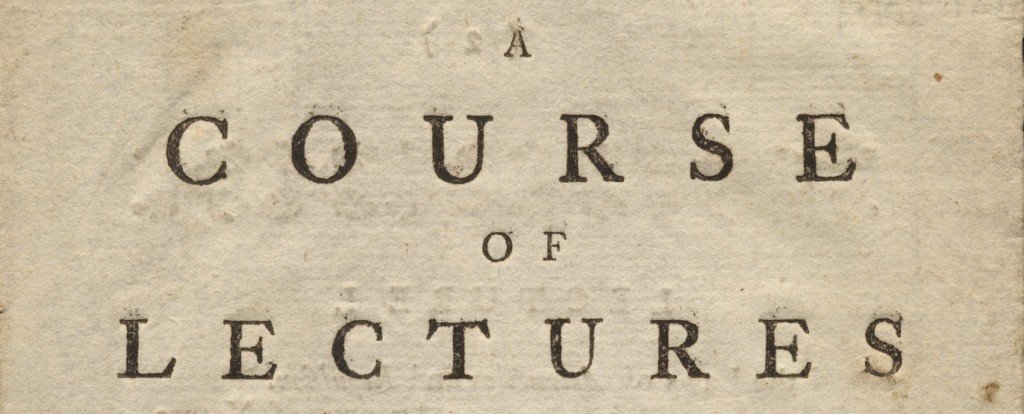

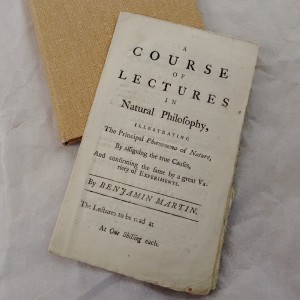

After a brief encounter with an orrery and an air pump, we moved on to the Seminar Room under the cobbles to feast our eyes on the literary and instrumental remains of Benjamin Martin, itinerant lecturer, author, publisher, instrument maker and all-round impresario of science in the mid-18th century. This was something new for the students. They knew about Boyle’s air pump and Hooke’s microscope, but had not yet heard my harangue about the rise of public science in the 18th century. The question arises naturally, though—the new science existed, so how did it spread? The first thing we learned is that it did not spread by itself. It relied on a whole economy of instruments and handbooks and magazines and polemical tracts, much of it represented, in all its concreteness, on the table before us.

Curator Dr Sophie Waring framed by Benjamin Martin’s Grand Universal microscope.

Another lesson was that science spread in several directions at once. Martin’s two-foot Grand Universal microscope, with its intricate brass feet and infinite adjustments, was not meant for the same customers as the more modest instrument that Stephen took out of a little wooden box. And Martin’s General Magazine of the Arts and Sciences, packed with mathematical puzzles and outlandish inventions, did not do the same work in the 18th century as the tedious table of numbers inside the Nautical Almanac—even if advertisements for both of these publications appeared on the classified pages of 18th-century newspapers, as we found out when Sophie gave us a short tutorial on the use of the British Library’s online database of early newspapers. Handily, the database is available from the University of Warwick library—a good starting-point for student essays.

Demonstrating history through telescopes

The Nautical Almanac led us to astronomy, and in turn to the Board of Longitude, the lunar distance method and the story of how an emerging group of professional astronomers fought for control over the Almanac and its endless numbers at the turn of the 19th century. By now it was 4:15, and according to the programme we were 15 minutes late for afternoon tea. But no-one seemed in need of refreshment—on the contrary—so instead of going to the café across the road we looked at it, through the four replica Galileo telescopes that the curators had laid out for us on the top floor. This exercise was at once surprisingly easy (I can read the words on that guy’s mug!) and impressively difficult (how did Galileo map the moon with this thing—it’s so shaky and squinty—let alone discover the moons of Jupiter?).

More instruments provided a hands-on exploration of the connections between navigation and astronomy, and we also moved from sea to land with a large-scale observatory quadrant attached to the wall. This mural quadrant reminded us why we were there. It’s one thing to sit in a lecture hall and look at a picture on a screen, it’s another thing to see the instrument in the flesh, to look closely at the divisions on the scale, to puzzle over the fact that there are two slightly different scales, and to be told that the divisions were considered so precise that no-one was allowed to enter the room when the engraver was marking the divisions off, for fear that extra body heat would mess up future measurements by causing the metal to expand.

We finished off the tour at 5:30pm in front of a William Herschel telescope (pictured) with Stephen telling the story of this 18th-century musician and composer who discovered an entire branch of astronomy in his spare time. Science was not complete in 1800: there were still new publics to attract, new instruments to build, new questions to ask—and much to look forward to in Warwick, where the 20-lecture course continues next week. The final word goes to the students. On my way home I bumped into one who, without the least amount of prompting, told me that the visit and the curators were ‘cool’. Coming from a discerning 19-year-old, this is very high praise.