Vaccine trials in Science and Art

In conversation with

portrait artist Fran Monks

Portrait artist and photographer Fran Monks sat down over Zoom with Izzy Treyvaud — one of our Gallery supervisors — to explore photography as a gateway to celebrating the extraordinary stories of ‘ordinary’ people.

Why did you choose photography as a career – and why portraiture in particular?

That’s starting with a really big question!

It kind of happened by accident.

For five years, I worked as an environmentalist for Shell, the oil company. I found it really hard, because it’s very difficult to change such a big organization. So I came out of that wanting to find out more about how people change the world around them.

At that point, photography was just a hobby.

Then, because of my husband’s job, I had the opportunity to live in Washington DC. Sometimes being overseas helps you do something that you might be scared to do in your own country.

As I got more work as a photographer, I started to explore how you make a difference by talking to — and photographing — people who are themselves making a difference.

Photography really works as a kind of gateway into having those conversations. I just like the opportunity to tell a story through a picture of a person.

We’re all fascinated by people, but certain types of stories are told more than others. And I found it really engaging and enjoyable to tell stories that weren’t being told so much, but also were quite positive.

I enjoy all the techy stuff, but I think if I didn’t have at the core of it that connection with another person — that’s what completes it for me.

How much do you plan in advance?

I’ve had to learn over the years that if you go in with a very clear idea of an image — and you’re only focused on that — you won’t necessarily get the bigger picture and the connection with the person.

If you’re really well prepared, it does allow you to relax more in the moment, and then do the chatting and the connecting and the finding out.

But you can’t always be prepared!

So when I’m doing Zoom portraiture, there are so many elements where I don’t know what I’m going to find:

What’s the bandwidth going to be like?

What’s the house going to be like?

It’s the same when you visit someone on location for a one-off portrait — I won’t necessarily know what I’m going to find.

Sometimes the things that you hadn’t planned are what make the portrait interesting.

Photographers often say to me about the Zoom portrait, “How do you take it? You can’t control the light!”.

You have to let go of that control — but sometimes the results are fantastic.

Your Zoom portraits combine image and words to tell the story — was that always your plan?

It’s evolved over time.

The most rewarding thing about my work is when you’re getting people to think about different types of stories.

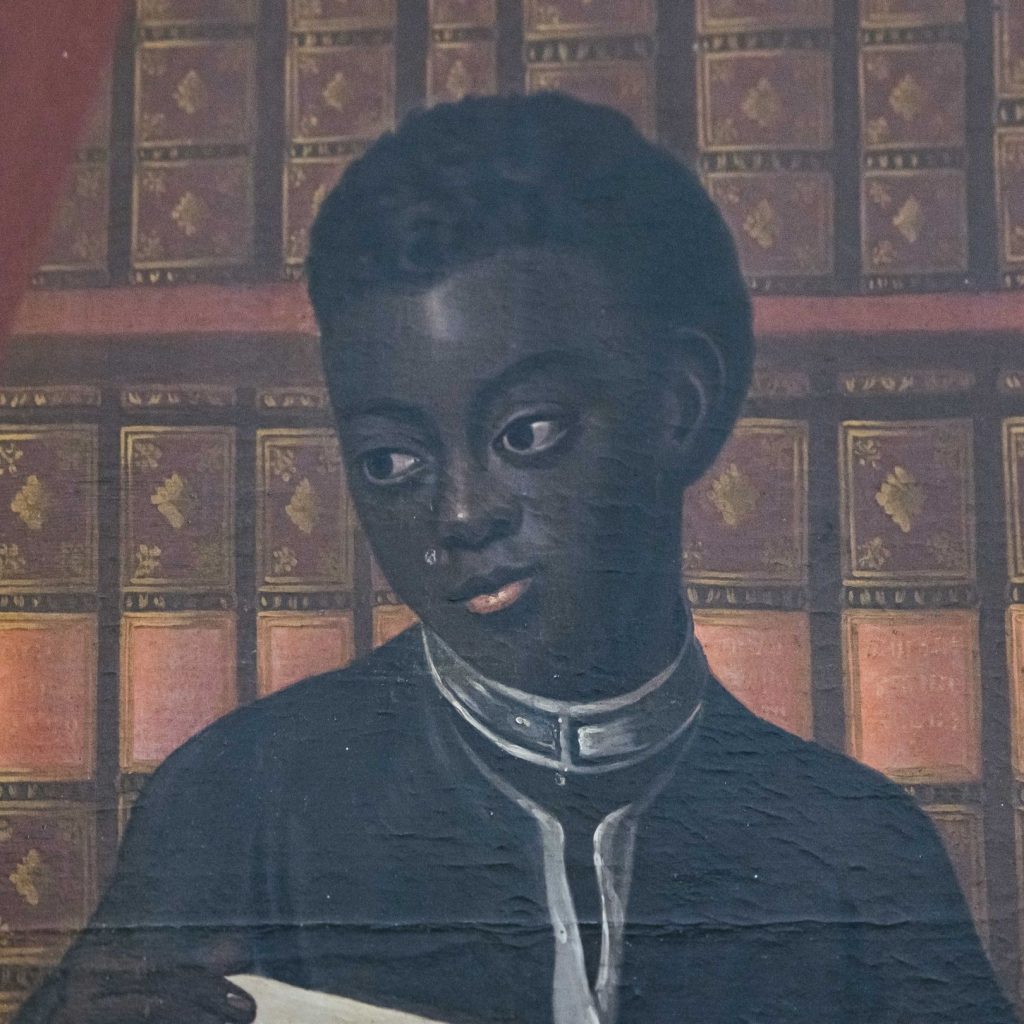

Part of that probably crystallized when I was working for some of the Oxford colleges.

A lot of them are thinking now about who’s on their walls and trying to make it more representative of the current student community.

Not all diversity is visible, so as a photographer you can’t always show that people are different.

I appreciated how much it meant to some of those people who otherwise would not have been represented in that kind of space. It really made me appreciate — re-appreciate — the power of that.

And it made me want to do it as much as possible: really respectful portraiture of people who wouldn’t normally be up there.

I’ve realized over time that for me, you can never tell the whole story with a still image. It needs text — a short story — as well.

I feel you’re really getting something more out of the image that way.

And it’s just more fun for me!

What’s the impact of working over Zoom for you — and the people you’re photographing?

In some ways, Zoom has opened up the world.

One of the first people I photographed was a lady in Melbourne who has been bed-bound for 20 years. She said to me:

You know, it’s amazing that I can participate in things now. Before I felt much more excluded; now everyone’s online, so now I can really feel part of it.

The interesting stories are the people like a woman I spoke to by the roadside in Malawi. She was trying to get back to her home village, so she gave her phone to some guy who was walking by. He held it and we took a picture.

That was her reality, but at least she was able to participate. Before she might have been completely excluded.

I want to carry on doing Zoom photography because I can access people who normally wouldn’t be able to get their story out there.

Part of me doesn’t want to let that go.

Why did you turn your attention to Covid-19 and the pandemic?

At the start, I was just photographing people who were in lockdown, because I realized we were living through an historic time.

And increasingly I began thinking that this is also about celebrating the under-celebrated.

If you make good images, then in 100 years, 200 years, this is what people are going to look back at.

So you’re thinking:

What stories do I want people in the future to be telling about now?

I realized there were lots of great pictures of the doctors and scientists, but just staying at home is harder to capture — because everyone was at home!

So I wanted to make those images and tell that story. And the vaccine trail participants just came to mind for me.

That’s a huge project – how did you get started?

I started with a friend who was one of the first 20 participants.

Once I had that picture, I could post it on Twitter and say, “Does anyone else want to be part of this?”.

And it just snowballed from there.

What was really special about meeting people on the vaccine trials was that they’d made this choice to do something, which I think is quite brave — and very, very important for getting us out of the pandemic.

Many said they’d been told to stay at home and do nothing and that was how they were contributing to keeping people safe. But they wanted to actually do something rather than nothing, and this is one way that they could do it.

Without them, we wouldn’t know how good these vaccines are — but a lot of them hadn’t really had the opportunity to talk about it.

I think it’s very easy with medical trials — I certainly am guilty of this — to think “Oh, that’s something that other people do”.

So it was really interesting to find out why people had taken that step.

There was one volunteer from the US who’d been a school bus driver her entire life. Then she found herself retired in a pandemic and thought, “Well, I can do something about this”.

And she just did it. She used to try drive two hours to the clinic to do all her tests.

Most of the people were very healthy themselves, apart from one young guy who was diabetic, so that was even braver, I think.

What are the main differences for you as a photographer working over Zoom compared with ‘normality’?

In ‘normal’ times, I like to photograph people on their home ground, because it’s their environment and they’re more relaxed.

What I found with Zoom is that people are still on their home ground, but I’m not actually in their space.

So they are completely in control, and I find that people are even more relaxed because of that. You have to collaborate — hold the screen and get them to show you around — and it can be quite challenging.

At the end of the day, I’m just on a screen, so I’m not imposing. And I think that changes the dynamic between the photographer and the sitter.

How did you frame the shots and choose the background when working over Zoom?

You try and find some kind of connection with people. Because it’s a collaboration, you do get to know people much better through the Zoom process than you would just by photographing them in real life.

So once we log on, we have a chat and I ask people to show me their space. Then I decide what might work.

We have to try a few things — as I say, it’s very collaborative.

Sometimes there’s someone there who can hold the computer, but more often than not people are on their own. It’s a very constrained process, which I like because it makes me take pictures that I wouldn’t normally take.

I like a very simple sort of aesthetic, and my instinct would be to cut out lots of distraction. But you can’t this way, so they’re usually much more wide-angled than I would normally go for.

After a while, I thought, “Hang on, we can move away from the camera and that makes it more interesting and more like a portrait.”.

I always chuckle, because people often say, “Oh, I haven’t tidied up!”, but I say, “This is Zoom — don’t worry. It’s all kind of blurry anyway!”.

It often surprises people that I actually photograph my screen with my camera.

I experimented a bit, and it’s just more interesting. Sometimes you get this ‘moiré’ effect which means there’s kind of a grid over the picture, or swirly lines.

I wanted to show that the picture is made with digital layer upon digital layer, rather than trying to be something that it isn’t.

But I do like the fact that, when I print them, the black border from my computer looks a little bit like an old starter in print.

When you’re working on Zoom, you’re in every image. How does that affect your work?

I love that!

Not because I love seeing my image in there, but having been a portrait photographer for a long time, I’m always thinking:

“What was the photographer saying?”

“What was the relationship between the two of them?”

Because the portrait is a reflection of the person that they’re interacting with, I think.

For me, having that little thumbnail there makes that more explicit.

So anyone who looks at the picture will remember, “Oh, yeah, there was someone making this picture as well”.

I hadn’t thought about it before, but — I’m never in the family photos!

Photographer and portrait artist Fran Monks was in conversation with Izzy Treyvaud.

The Vaccine Trials – in Science and Art display of Fran Monks’ Zoom portraits in the History of Science Museum was produced in partnership with the Photo Oxford Festival 2021

All images © Fran Monks

More to explore

Watch Fran Monks In Conversation on YouTube with Professor Sir Andrew Pollard, vaccine trial volunteer Dr Helen Salisbury, and History of Science Museum Director Dr Silke Ackermann. Chaired by economist, journalist, and broadcaster Tim Harford.

Vaccine Trials – in Science and Art online gallery

The Art of Science – online gallery displaying glass sculpture of a single nanoparticle of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine by artist Luke Jerram