Astrolabes, iPhones and Fakery

Tom with the genuine article, an astrolabe made by Abd al A’imma. Inv. 48701

Tom, from the Museum’s Young Producers group, talks about astrolabes and the craftsman Abd al A’imma.

**

It is easy to forget the past.

This is perhaps most true of technology. We have no reason to think about it, but every day we do something utterly radical. We reach for a smartphone, and we’ve harnessed the power to combine communication with unbounded access to knowledge.

Our devices do lots besides connecting us. On mine I have one of several free apps that lets me point it at the sky and find the names and positions of whatever stars and planets I’m facing. If you install something similar, in seconds you’ll have in your pocket a tool far better than anything owned by your stargazing predecessors in Persia.

The Age of the Astrolabe

With such information so easily to hand, one could be forgiven for forgetting about the age before computers: the age of the astrolabe. In fact, there’s already a superb article about the parallels between these two handheld devices [1].

One need only look at any of the astrolabes here at the Museum to know that their value extends far beyond their function. The finery and creativity of their decoration says more than words could about the astrolabes’ other purpose: status symbols.

The rete of an 18th century astrolabe made by Abd al A’imma. Inv. 48701

A modern analogy could be an expensive wristwatch. It seems the basic idea is the same today as it was in eighteenth-century Isfahan, even though they didn’t actually have wristwatches.

Everyone needs to tell the time, but if you have the means, you may be tempted to tell it with something flashy. In Persia (and in Europe amid the Scientific Revolution) people also needed to predict sunsets and sunrises, chart the stars, and measure latitude. An astrolabe could do it all and more.

Despite newer and better instruments, its versatility and portability maintained it as the must-have motif for an era when science was in vogue.

Naturally some astrolabes were nicer than others. The ultimate state of the art was around 1720, just before the fall of the Persian Safavid dynasty, and it involved a craftsman named Abd al A’imma. His skill as one of history’s finest astrolabe-makers is evident in his work held at the Museum. Other museums have pieces bearing his name, and some of them are wonderful for quite a different reason: they’re fake.

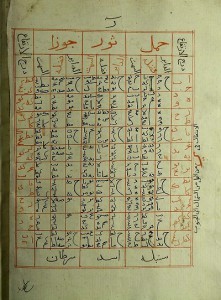

The umm of an astrolabe, engraved with a gazetteer. Inv. 48701

Fakery and Brand Names

Their existence confirms al A’imma’s prowess not just as a craftsman, but as a brand name. They reveal themselves in much the same way as would a fake Rolex or a knockoff Gucci bag. The details are off; the fit and finish aren’t up to standard – there are even misspelled engravings, an artefact of the Persian forgers’ poor grasp of Arabic [2].

Perhaps we should take a cynical view of all this. Materialism and fakery are as old as can be. Amazing technologies are doomed to start out as an art practised by experts, then become an exclusive pursuit, then end up as a commodity. Even precise timekeeping, once the domain of astronomers, has long become a forgettable feature of our ubiquitous smartphones.

We can think better. Why might something be imitated? The obvious answer is that it has a value deeper than the sum of its materials. And when that value is associated with something so scientific, so insightful, so ingenious as an astrolabe, surely we owe our respect to the culture that made it worth faking. The Abd al A’imma forgeries, by existing, demonstrate a reverence for science, and a desire to practise it.

Astrolabe plate by by Abd al-A’imma marked as a tablet of horizons. Inv. 48701

Does the same desire exist today? Our answers depend on individual belief, yet many of our most pressing global issues depend desperately on a collective belief that scientists and experts must be listened to, and trusted. Maybe this culture existed more in 1720 than it did today, which would mean the advancement of time does not guarantee the advancement of thinking.

So when we take a moment to consider the phoney astrolabe, the fake Rolex, or the 5G Samsung, we remember the history of science that connects them – science which, just like them, exists for a reason.

[1] Jane Louise Kandur, Astrolabe: the 13th Century iPhone, Daily Sabah, 2015.

[2] Gingerich, King, and Saliba, The Abd al A’imma Astrolabe Forgeries, Journal for the History of Astronomy, vol 3, pp. 188-198, 1972.

**

Tom Franklyn Gammage is a science writer for the upcoming film ‘My Flatmates and Me’, a documentary about modern “flat-earth” belief. He also writes for Macat International to promote the teaching of critical thinking in schools. He has been involved with the Young Producers group since May 2017.