Young Producers Curating Prayer: A display in the Islamic World collection

Over the last year the Young Producers voluntary group at the History of Science Museum, made up of Ellie Martin and Sam Hudson, has been working with the collection of scientific instruments from the Islamic World display in the top gallery creating new designs based upon feedback from an earlier public consultation project Curate, run by the learning team, which enabled us to identify specific objectives needed for the improvement of the interpretation of the Islamic World collection.

This collection contains many unique instruments including astrolabes. The History of Science Museum holds the largest collection of astrolabes in the world, so we thought it important that these beautifully crafted scientific instruments were highlighted in a more modern and accessible way.

The current display had remained largely the same for at least 20 years and desperately needed a revamp to make it more vibrant and engaging. Previous interventions by our group had added new information cards and a map, but this time we hoped to do something more ambitious.

As a group the Young Producers narrowed down some core themes that we wanted to reinterpret with our new displays; craftsmanship, religion and science, cosmology, diversity and knowledge exchange. In groups of two or three we split our work. Our group consisted of Sam Hudson, Ellie Martin and Phoebe Homer, and together we chose to develop an intervention on the functional aspects of the instruments; specifically, how they would be used when performing daily prayer within Islam.

In the cabinet, there already existed a small section that dealt with this theme (figure 2). However, we saw a few problems with it. Firstly, despite mentioning how some astrolabes contained prayer lines and gazetteers that would help you find the times for prayer and the direction of Mecca (qibla), neither were visible. This was because the front (rete) and plates (tympans) of the astrolabes had not been removed and so obscured the visitors’ view of both. Also, as the astrolabes were fairly small, any close study of them was difficult. We also felt that the current display lacked a fundamental human element, which made it hard for the viewer to connect to the objects. For instruments that were so crucial for facilitating Islamic beliefs, we decided that this was something that needed to be altered. Lastly, we agreed that the current labels were too complicated making them inaccessible, and that the whole display needed to be more eye-catching. Our section of the case is located right next to the gallery door and we wanted to utilise this location, providing a vibrant, engaging display that will draw the visitors’ attention.

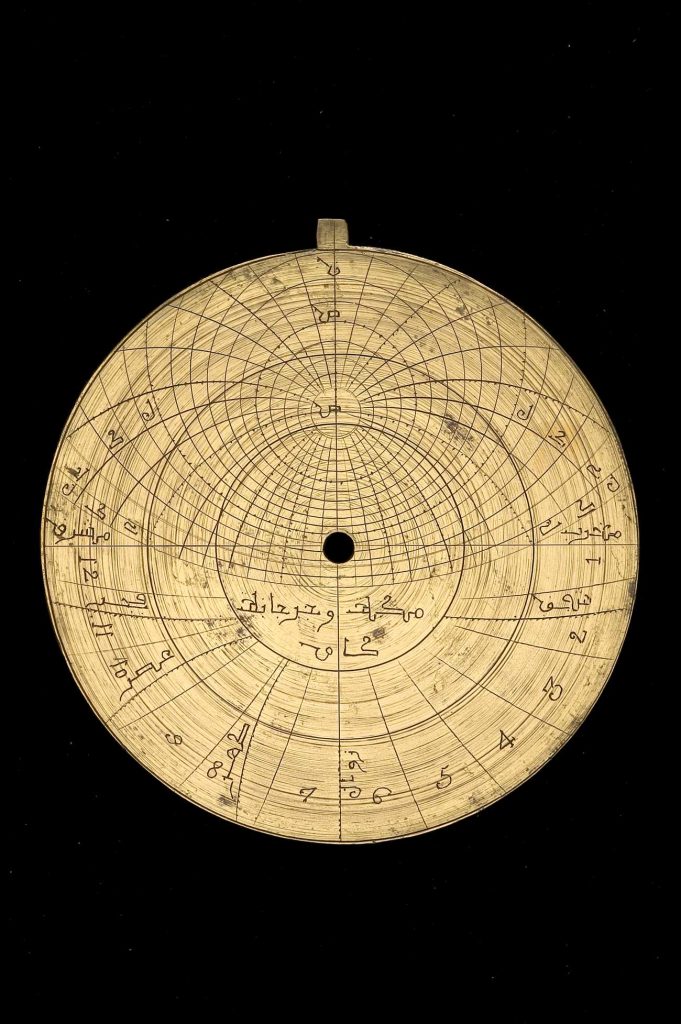

To solve the first problem, we chose two new astrolabes to add to the display. The first – astrolabe 47714 (figure 3) – could be displayed with its rete removed so that the clear prayer lines for the 5 daily prayers could be seen. The second – astrolabe 35313 (figure 4) – had a beautiful gazetteer listing the direction of Mecca for 46 locations. This could be displayed with both its rete and its tympans removed so that the gazetteer was visible on the back. Additionally, an enlarged image of 35313 was planned so that visitors could clearly see the cities marked on the gazetteer with translations of their Arabic names. For the translations we sought support from the Multaka Project, a mixed group of Syrian and other forced migrants volunteering with the History of Science Museum. They were incredibly helpful in helping with all aspects of the display and Rana Ibrahim, Collections Officer for the project, was really supportive offering advice and translation. These initial changes helped to make the display more accessible and easily understood.

Figure 3: The plate from astrolabe 47714 showing prayer lines for the five daily prayers.

Figure 4: Astrolabe 35313 displayed without its’ rete and plates so the gazetteer is visible on the mater.

To give the display a more human touch we decided to include not only historical artefacts, but some contemporary objects. This included a modern prayer mat, prayer beads, a Qur’an and a contemporary Qibla indicator (figure 5). A Qibla indicator is a modified compass (figure 6) that points the user in the direction of Mecca. By adding a contemporary version we aimed to demonstrate the continuity of Islamic practice over time.

Finally, we re-designed the back panel, on which we planned to incorporate Islamic geometric designs (which involved many failed sketching attempts!). Thanks to the creativity of the Museum’s in-house designer, Keiko Ikeuchi, we included not only patterns, but an image that demonstrates Islamic prayer. The prayer mat was our last addition to the case. In order for it to be included, conservation required it to be frozen for two weeks to kill off any insect contaminants. Once it was in, it added an aspect to the display that catches your attention immediately and worked well with the prayer beads and Qur’an placed on top.

Figure 5: A contemporary plastic Qibla indicator

Figure 6: A Qibla indicator from the collection used in the display

After around six months’ work, we installed the display on the 30th August (figure 7). We hope that you agree that the space appears more vibrant and eye-catching than before. The contemporary objects were placed upon the prayer mat, along with two Qibla indicators, to give that section of the display a more casual, personal appearance. All of the labels were rewritten so that they were engaging and informative but accessible, with an enlarged and more modern font. Islamic patterns were included on the base panel and, a last-minute addition, we included a standing label about the first Muslim astronaut in space provoking the visitor to imagine how a Muslim might pray in space! We felt that this extra, fun bit of information would make a contemporary link with the new display helping visitors to engage with the content.

After such a long process, we are so happy to see our ideas become a reality. As a group we agree that the end result far exceeds what we imagined in our minds (and pages and pages of rough drawings!). Depending upon time and resources, we are hoping to add more new displays to the cabinet inspired by other groups from the Young Producers. The combined effect should bring a completely fresh interpretation to the objects, and we are all really excited to see how this project evolves. We would like to thank all of those at HSM who helped us along with way, particularly Chris Parkin (organiser of the Young Producers programme), Rana Ibrahim (Multaka Project) and Keiko Ikeuchi for the beautiful graphic designwork.