The Museum is famous for its collection of astrolabes, the largest and most significant in the world and particularly strong in Islamic instruments. An astrolabe is a brilliant astronomical device used, very roughly speaking, for timekeeping. But as researcher Taha Yasin Arslan explains, timekeeping in the medieval Muslim world involved many different things…

by Taha Yasin Arslan

Perhaps the most fundamental definition of timekeeping is the reading of the position of the Sun or stars. But in the medieval Muslim world it had a much broader meaning. Knowledge of timekeeping or ilm al-mīqāt covered the finding of instantaneous time; the times of the five daily prayers; the direction of Mecca; as well as making instruments and writing manuals for observational devices. People who worked on timekeeping were called muwaqqīt or mīqātī, which means ‘timekeeper’.

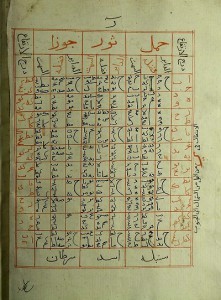

Arabic tables for timekeeping

Timekeeping in the medieval Muslim world started in Baghdad in the 9th century, but it was the Mamluk-era (1250-1517 CE) astronomers who lived in Egypt, Syria and Palestine who were the real deal. They studied all branches of astronomy but specialised in timekeeping. They prepared tables and invented practical instruments for observation and calculations. In fact, they were excellent instrument makers who made some of the best astrolabes, astrolabe quadrants and sundials in the history of astronomy. Several of these instruments are here in the Museum’s collections.

I am particularly interested in how these instruments were made and used, and how the meticulous and complex tables were drawn up. The astrolabes have many parts, markings and scales and are not easy to understand at first glance. So I have decided to study timekeeping in detail; and the more I studied it the clearer it became that these tables aren’t so hard to understand after all. In fact, the astronomers prepared the tables for timekeeping so that the less initiated would be able to find the time without making extensive observations or calculations.

The same idea was applied to instruments. Astronomers made the instruments user-friendly, even for beginners. Once you learn basic and simple principles, you would know how to use any astrolabe or any other similar instrument.

Replica of Ibn al-Sarraj’s Universal Astrolabe by Taha Yasin Arslan

Preparing tables and making instruments demands an extensive knowledge of spherical trigonometry and astronomy, but using them doesn’t. As a student of the history of astronomy, the best way for me to understand how they work has been to prepare the tables and construct the instruments myself. So, that’s what I did.

First, I have learned the formulas for the markings (altitude, azimuth, hour-lines…) on the instruments. Then I drew various instruments on the computer. Finally, I was ready to make the instruments. With my brother’s help for the 3D modelling, and the pursuit of at least five different artisans for every instrument, I have managed to make my own devices. Some are replicas of medieval instruments, but some are my own adaptations in the same tradition.

When you take an instrument made with your own hands, understanding how it works becomes so easy and it feels amazing. When you appreciate how hard it is to make an instrument, even in these modern times, it’s a wonder how people a thousand years ago managed to make the beautiful objects that you can see in the Museum now.

Building time machines like this is a noble and beautiful endeavour indeed!

Replica of Bayezid Astrolabe by Taha Yasin Arslan