Making science the hero

Celebrating International Women and Girls in Science

Tina Eyre, Curator of the Collecting Covid Project at the History of Science Museum, shares contributions from women and girls to the Covid-19 pandemic response

Every year on 11 February we celebrate International Women and Girls in Science Day.

The United Nations (UN) launched it in 2015 because — despite progress — women and girls are significantly underrepresented in science.

The UN sees full participation in science as an important step towards complete gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls.

Meeting successful women in science

I’m proud to be the Curator on a project which every day reveals that empowerment in action.

I started work as Curator of the Collecting Covid Project in November 2021.

Since then, I’ve met many strong successful women with ambitions in the field of science.

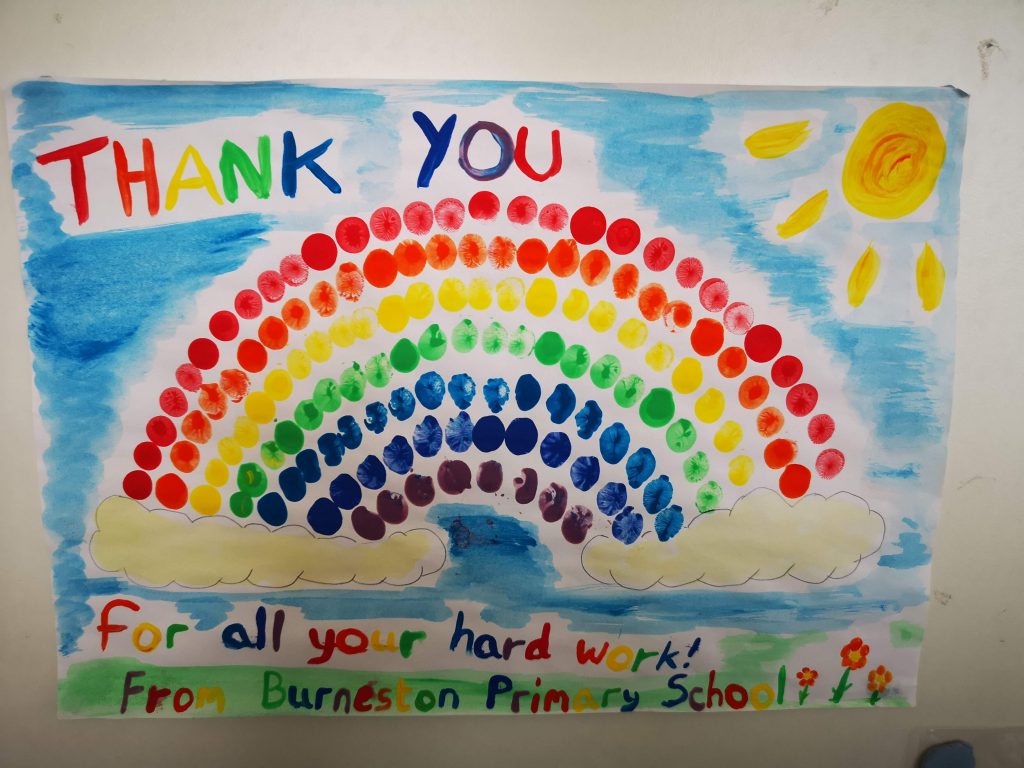

They include internationally recognised names like Professor Dame Sarah Gilbert — and young girls sending thank you letters to the vaccine team.

What is Collecting Covid?

Collecting Covid is a joint project between the History of Science Museum and the Bodleian Libraries to capture Oxford University’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Both institutions also have long-standing collections featuring notable women scientists, including Dorothy Hodgkin and Louise Johnson.

Professor Sarah Gilbert & the Covid-19 vaccine team

Professor Sarah Gilbert recently donated the first part of her archives to the project.

Made a Dame for services to medicine and public health, Sarah is the leader of the Oxford ChadOx1 Covid-19 vaccine team at the Jenner Institute.

Professor Gilbert has said:

[I’m] passionate about inspiring the next generation of girls into STEM careers and hope that children who see my Barbie will realise how vital careers in science are to help the world around us.

Professor Dame Sarah Gilbert

She’s received many honours. Maybe the most unusual was from toy company Mattel, who produced a Barbie doll in her likeness.

Making science the hero

This is all brilliant coverage. It has inspired many girls from around the world to write to Sarah and thank her.

But some might ask whether it gets the right message across to girls from and from all backgrounds across the globe.

By making a hero of a single, brilliant (white) scientist, don’t we make the career seem elitist? Is science out of reach for the average girl?

Professor Gilbert herself has always acknowledged and thanked her team.

She sees the science — and not herself — as the role model.

We did not have time to think about how dangerous this virus was, we just did our job.

I could see how hard and devotedly our scientists worked, doing day and night shifts.

The atmosphere was nice and friendly.I think, we all were getting closer, like one big family.

Mariya Mykhaylyk, Lab Assistant at the Jenner Institute

So this singling out of the team’s leader is a media invention.

A ‘hero genius’ makes for a good story: a long hard slog by a team of hardworking scientists doesn’t.

Shouldn’t we instead celebrate the role of the whole vaccine team with its many women? Wouldn’t that better showcase the range of opportunities and variety of people involved?

Knitting the stories together

At the Collecting Covid Project, we see a surprisingly wide range of pandemic-related work.

So far, we’ve tracked down equipment, stories, beer bottles — even virus-themed knitting!

And that means celebrating the very many staff involved at all levels.

Here’s just one example from Marion Watson, Head of Operations at CCVTM where the clinical aspects of the Covid-19 vaccine trials took place.

Marion told us:

I did my degree and PhD at Imperial College London when there were only 8% women there (1976-1982).

Sometimes the men treated us as a commodity rather than peers.

The UK is so much better than it was (but still not equitable), let alone the wider world.

Marion Watson, Head of Operations at CCVTM

More on Collecting Covid

Keep an eye out for more news as the Collecting Covid project develops.

These are the first contributions from strong, ambitious, capable women.

I’m confident they won’t be the last.

Tina Eyre is Curator of the Collecting Covid Project at the History of Science Museum.