By Tony Simcock, Museum archivist

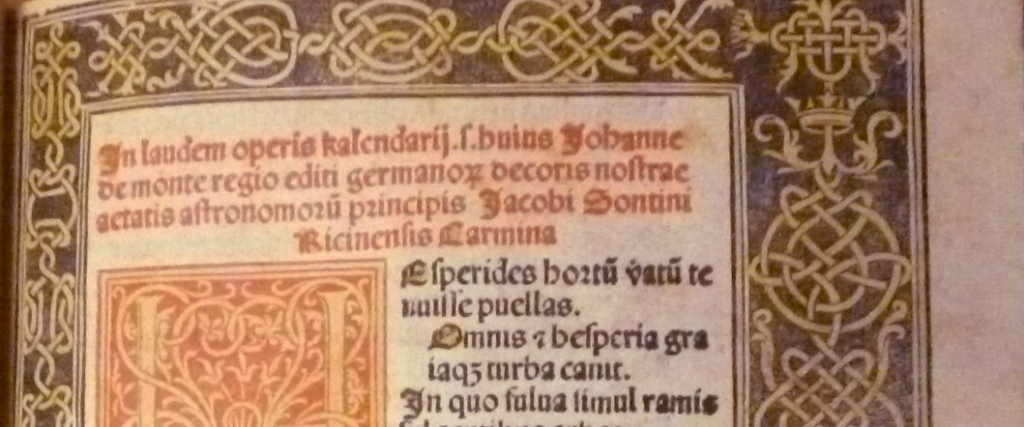

Here is one of the Museum’s oldest books. Indeed, it is one of the first and most influential scientific books ever printed. It is the 1482 astronomical calendar compiled by Johannes de Monte Regio – his name can be seen at the end of the first and beginning of the second lines of the title-page (if it can be called that – title-pages hadn’t really been invented yet). Posterity knows  the author as Regiomontanus, and honours him as one of the founders of the scientific renaissance – the dramatic revival of scientific learning and curiosity at the end of the Middle Ages.

the author as Regiomontanus, and honours him as one of the founders of the scientific renaissance – the dramatic revival of scientific learning and curiosity at the end of the Middle Ages.

We tend to think of the ‘Man in the Moon’ as a face occupying the Moon’s disc, though in earlier folklore he was imagined as a full-length figure, perhaps a little hunched and chilly, accompanied by a dog and a bush, or bunch of twigs. He is ‘yonder peasant’ whom King Wenceslas noticed gathering firewood in the snow. Shakespeare describes him similarly in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (about 1595):

This man, with lanthorn, dog, and bush of thorn, Presenteth Moonshine.

That’s what people gazing at the full Moon at that period made of the various dark shapes.

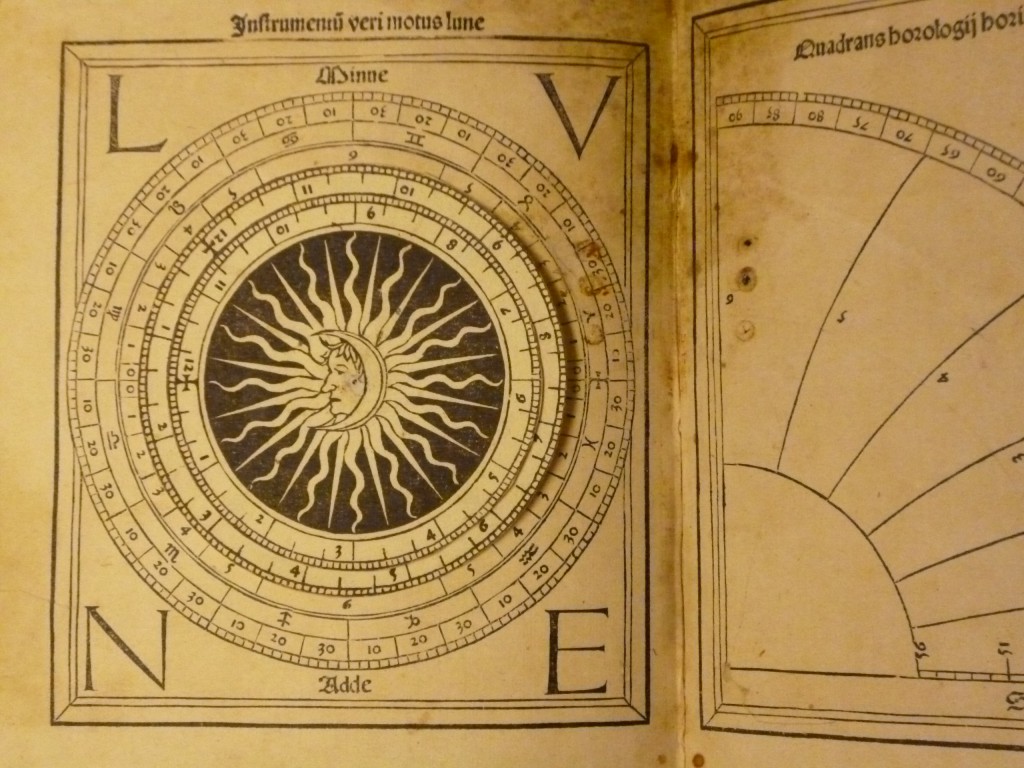

One un-typical early face in the Moon, however, represents something more than either folklore or optical illusion. Modelled into a crescent moon at the centre of a lunar volvelle in our 1482 book is a realistic profile face with distinctively rugged nose. It seems to be an authentic contemporary portrait of Regiomontanus himself, who had recently died at the early age of 40.

This posthumous edition of his astronomical calendar was printed in Venice by Erhard Ratdolt, a great admirer of Regiomontanus and himself a pioneer of scientific printing and illustration.

The Man in the Moon: Regiomontanus himself

The first edition of the work had been issued at Nuremberg where, in about 1470, Regiomontanus set up a printing and publishing business, as well as an instrument making workshop. He was the first publisher of astronomical books. His vision was not one of cloistered scholarship for a learned élite – he set out to use the recently-invented printing press to disseminate mathematical and astronomical knowledge, and to make instruments for calculation and time-telling more widely available. Four real instruments, but printed on thick paper rather than expensively engraved in metal, are included at the end of his book.

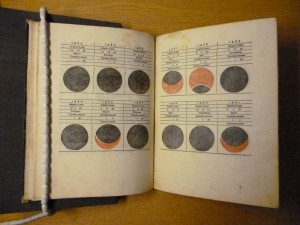

It was thus much more than just a calendar; it was a compendium of astronomical and mathematical information with an overtly practical and educational purpose. It includes charts for daylight hours, phases of the Moon, and dates of Easter, with an explanatory essay, and an innovative calendar of predicted solar and lunar eclipses down to 1530. The pages providing an at-a-glance eclipse calendar by means of diagrammatic pictures of total and partial eclipses seem an obvious idea now, but it was the first time this simple visual technique had been used.

It was thus much more than just a calendar; it was a compendium of astronomical and mathematical information with an overtly practical and educational purpose. It includes charts for daylight hours, phases of the Moon, and dates of Easter, with an explanatory essay, and an innovative calendar of predicted solar and lunar eclipses down to 1530. The pages providing an at-a-glance eclipse calendar by means of diagrammatic pictures of total and partial eclipses seem an obvious idea now, but it was the first time this simple visual technique had been used.

Study of the Moon may have had a long way still to go, but the Regiomontanus calendars were a giant leap in the direction of modern scientific knowledge. How appropriate that Ratdolt should add this touching tribute to his mentor in the 1482 reprint, and in so doing bequeath us a uniquely down-to-earth take on the Man in the Moon.