‘Women and Science’ Series – From burnt toast to the Big Bang: How galaxies at the beginning of time affect your breakfast

Dr Rebecca Bowler is a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Oxford. Rebecca’s research involves studying some of the early galaxies that formed within the first billion years in the life of the Universe. In this blog post, Rebecca talks about the thing that inspired her to pursue a career in astrophysics. Burnt toast, and her mum.

My mum always burns her toast. Always. It used to drive me crazy as a teenager.

It was about that time, at the end of secondary school, that I started to get interested in astronomy. I fell upon a book called The Magic Furnace by Marcus Chown. It explains how those Carbon atoms that make up the burnt layer on my mum’s toast were created in the cores of stars. I was hooked.

As I studied more physics, I learnt that there was a time before a single Carbon atom was formed. After the Big Bang, the Universe was a vast, hot, empty* and somewhat boring place. Nothing as exciting as Carbon existed, because no stars had yet formed. It took a few hundred million years for things to start to get interesting again, with the formation of the first generation of stars and with this, the first illumination of the Universe with starlight. These stars were nothing like those we see in the night sky. Because of their different chemical composition they were monsters, with a single star containing hundreds or even thousands of times the mass of our Sun.

*empty of “stuff”, no planets, no stars, just some Hydrogen and Helium atoms drifting around. Plus dark matter.

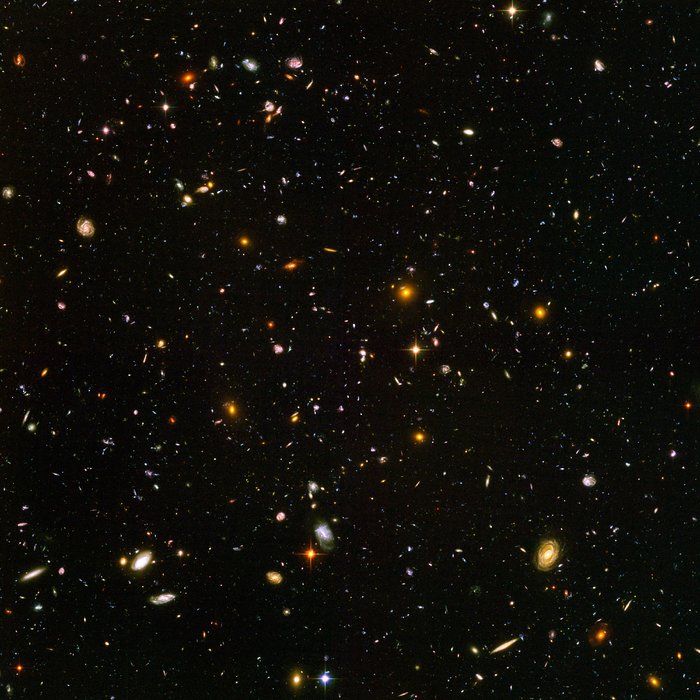

Today I research the formation of the first generation of stars and galaxies that formed after the Big Bang. Using telescopes, it is possible to capture the light from incredibly distant galaxies. Because of the vast scales involved, the light from some of these galaxies has travelled for over 13 billion years to reach our telescopes. This means that by looking at an image of a galaxy, we are seeing into the past, glimpsing how that galaxy was many billions of years ago. Images like the Hubble Ultra Deep Field is therefore like a time capsule for astronomers, with each point of light pinpointing a galaxy at a different distance and hence time within the Universe.

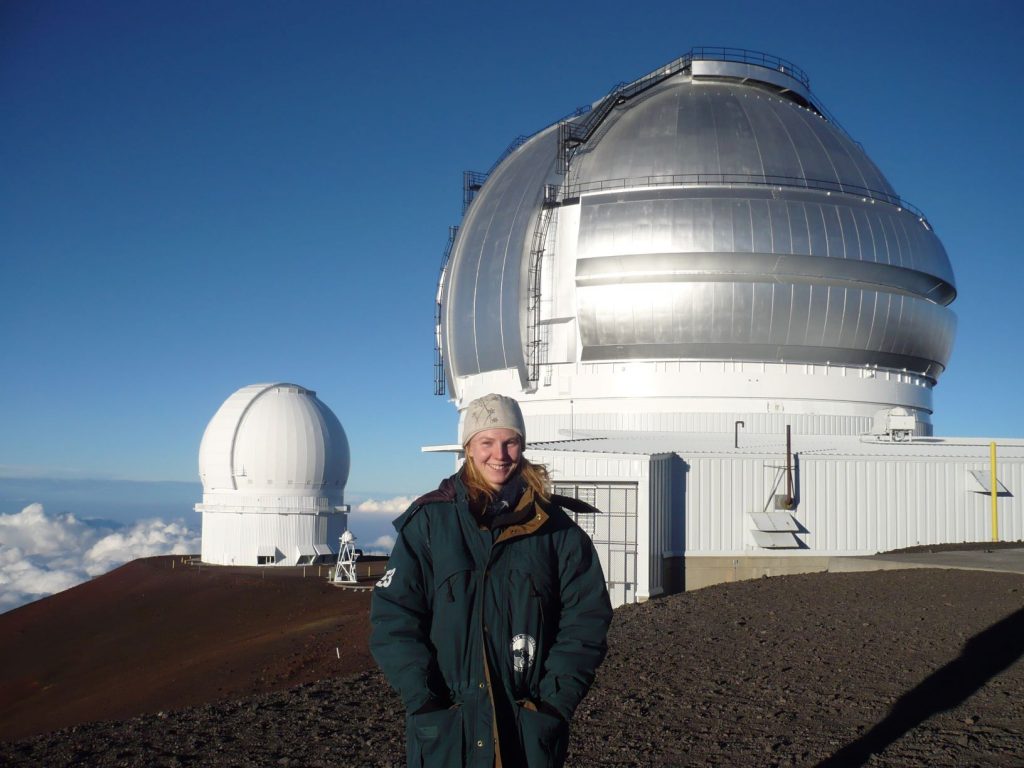

With these observations of galaxies, it is possible to find out what the Universe was like back in the first billion years. The chemical composition of the stars is imprinted onto the light we observe. I work with telescopes around the world, including the Hubble Space Telescope, to discover early galaxies and search for the fingerprints of the first stars. Back in 2012 I visited the Gemini North Telescope in Hawaii to make observations.

Standing on the summit of the mountain, surrounded by all the humongous telescopes, I was reminded of how far I’d come since opening The Magic Furnace ten years previously. When I burnt my toast that morning after 14 hours observing through the night, I was one step closer to understanding how those Carbon atoms came to be. But I was still no closer to understanding why my mum always burns her toast.