Epidemic encounters

Waldemar Mordechai Haffkine

and the Acland family of Oxford

Giles Hudson traces the history of vaccine pioneer Waldemar Mordechai Haffkine’s connections to Oxford’s influential Acland family, and his 35-year friendship with groundbreaking photographer Sarah Acland.

In a recent article on BBC News, Joel Gunter and Vikas Pandey described the bacteriologist Waldemar Mordechai Haffkine as “the vaccine pioneer the world forgot”.

Haffkine created the world’s first vaccines for cholera and bubonic plague, over 26 million doses of which were produced in India between 1897 and 1925. However, the consequences of the mishandling of one vial meant that until recently his contribution to the fight against infectious diseases had been overlooked.

As well as his achievements with vaccines, Haffkine also had links to Oxford that have been forgotten; links that have led to a number of fascinating photographic and archival items surviving in the collections of the History of Science Museum and the Bodleian.

Friendship with the Acland family

Haffkine’s connection to Oxford crosses the histories of public health, photography, and one of the city’s most influential families: the Aclands.

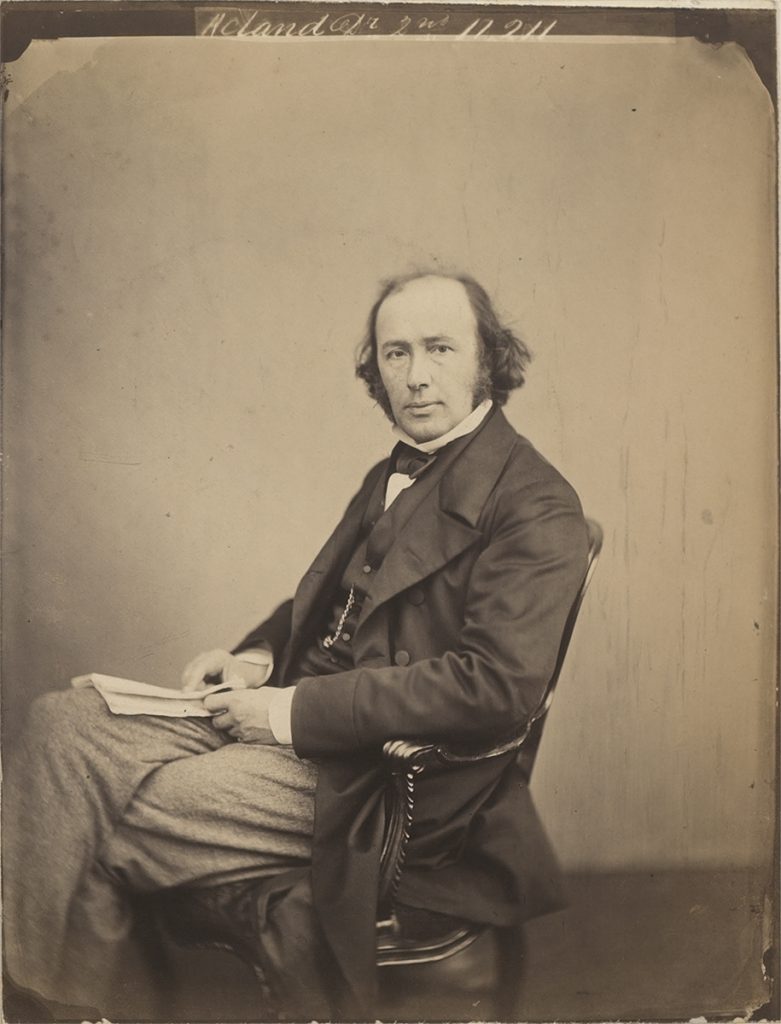

The Acland family — under the leadership of Sir Henry Wentworth Acland, Regius Professor of Medicine — played a seminal role in the academic, civic, and scientific life of Victorian Oxford. In their large house on Broad Street (since demolished to make way for the Weston Library), they received many of the most eminent men and women of the day, Haffkine included.

Maull & Polyblank, “Dr Acland” (albumen print, 1860)

Bodleian Library, MS. Photogr. b. 34, f. 151

The friendship between Haffkine and Sir Henry Acland originated in their common interest in the treatment of epidemic diseases. But it also outlived Acland himself, extending to his daughter, the pioneer colour photographer Sarah Angelina Acland.

Haffkine’s relationship with the family can be traced through Miss Acland’s letters and photographs, which provide additional insights into her family’s contribution to the progress of public health, at home and abroad, and the effect — all too often tragic — that some of the most prevalent infectious diseases of the age had on their lives.

Sir Henry Acland and the fight against cholera

Sir Henry Acland’s reputation as a physician and administrator was first cemented by his work during one of Oxford’s worst public health crises of the 19th century: the 1854 cholera epidemic. In his role as Physician to the Radcliffe Infirmary, Acland took control of organising the city’s response to the outbreak, at a time when the microbial vector of the disease had still to be identified, and uncertainty surrounded effective clinical treatments.

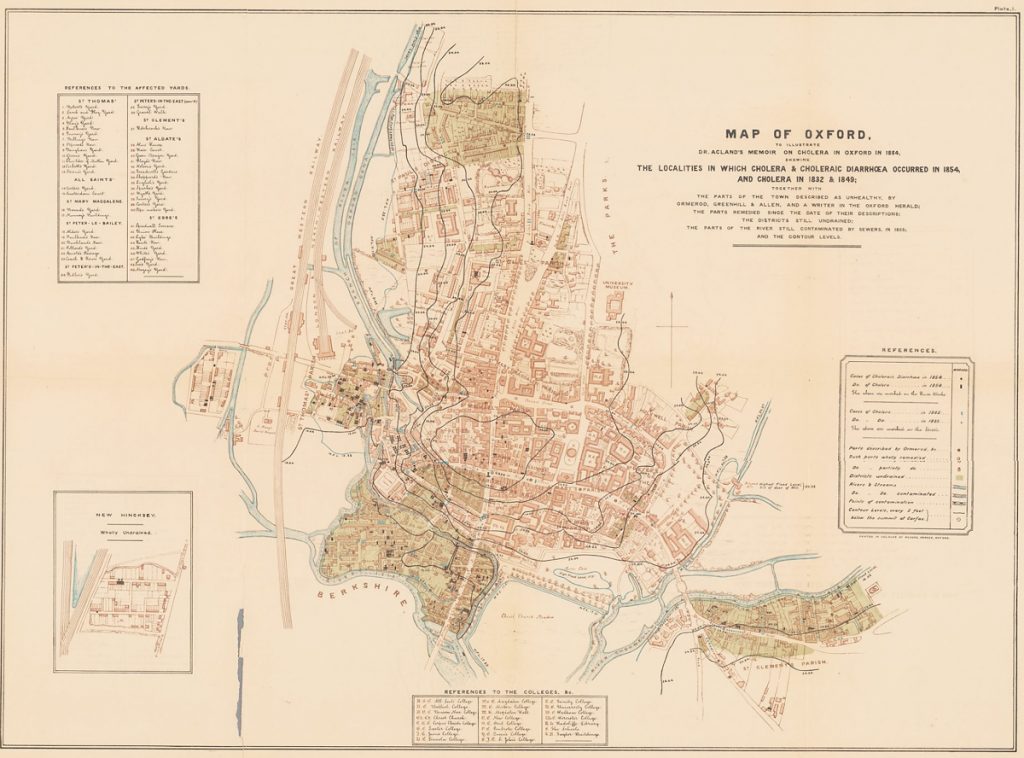

Acland’s Map of the Cholera in Oxford, 1854

Henry Wentworth Acland, Memoir on the Cholera at Oxford, in the Year 1854 (J. H. & J. Parker, Oxford, etc., 1856, plate 1)

https://exhibits.stanford.edu/blrcc/catalog/rt260gd2393

Acland was obsessive in his organization of measures to control the cholera. Under his direction a system was implemented for treating people at home, rather than in the stigma of a cholera hospital (or ‘pest house’, as it was known).

He also set up a ‘Field of Observation’ north of Jericho, to monitor people who had been in contact with the infected, established a system of messengers to distribute food and medicine, and documented the epidemiology of the outbreak in minute detail in his Memoir on the Cholera at Oxford.

Due to these efforts, the Oxford cholera was limited to 129 deaths from 317 cases, albeit in the face of no small difficulties. In Acland’s biography, J. B. Atlay reflected on the challenge encountered, in eerily familiar terms:

The history of one ‘plague’ is very like that of another … There is the same mixture of panic and recklessness, of utter selfishness and of super-human devotion, the same hideous agony in the midst of callous debauchery … There is always the same picture of over-worked doctors with their heroic followers, men and women, clerical and lay, striving to make up for the sins of neglect and commission which have rendered such a visitation possible.

Growing up in the shadow of disease

Sarah Angelina was five years old when the cholera broke out and was quickly dispatched to the countryside to escape the contagion. After her return, public health issues became the major preoccupation of her father and an ever-present subject of discussion in the house.

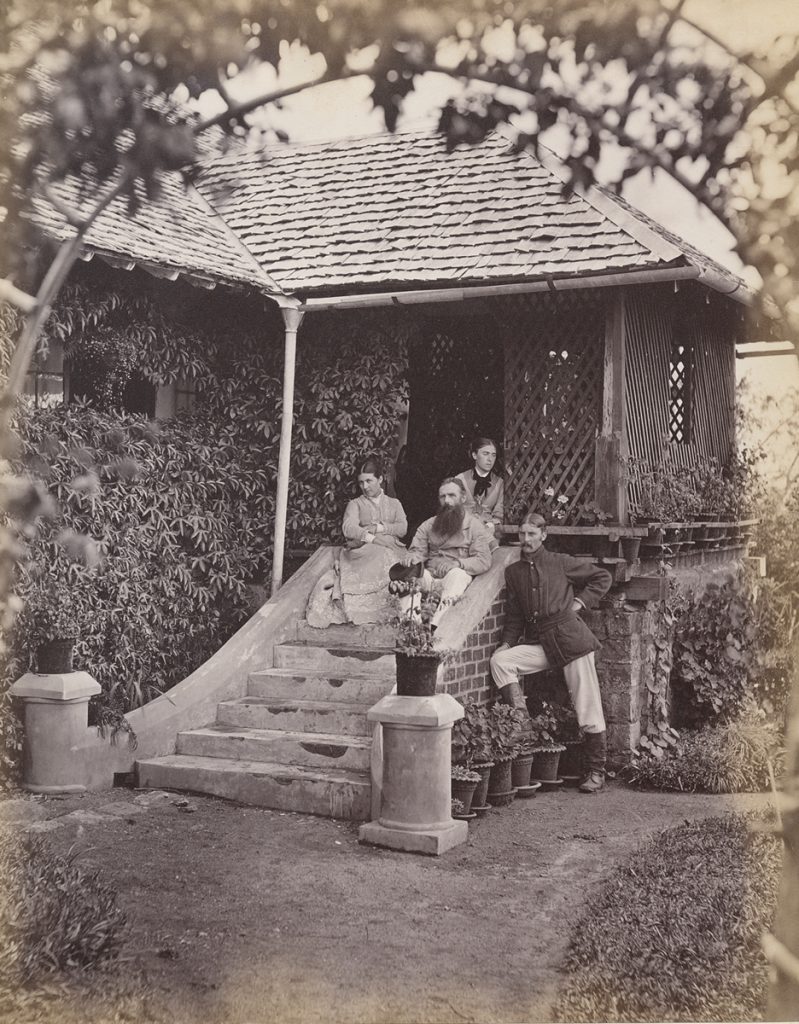

Unknown photographer, “Father, Mother and Children” (albumen print, c. 1876)

The Aclands of Oxford: from left to right, Alfred, Theodore, Sarah, Harry, Willie, Angelina, Frank, Herbert, Reginald, and Henry Acland

Bodleian Library, Ms. Photogr. c. 175, f. 152

On one occasion, for example, her mother would write to her eldest son that the previous night’s dinner had been

rendered more piquant by the presence of the Sanitary Commissioner

adding that

you may imagine that we did not lack for discourse on sewage.

Although cholera would not return to Oxford, the danger of other infections was never far away during Miss Acland’s childhood. One of the most regularly recurring was scarlet fever. Mrs Acland’s letters mention numerous cases in Oxford, many of which proved fatal.

In the early 1850s, for example, scarlet fever struck the Acland’s closest Oxford allies: the family of Henry George Liddell, Dean of Christ Church. The Liddell’s second son, Arthur, died from the infection, aged only three.

Later Mrs Liddell would also catch the disease, with the result that her three youngest children had to be quarantined in the Acland house. Her daughters Ina, Edith, and Alice (of Wonderland fame), on the other hand, were able to stick it out in Christ Church, as they had already gained immunity.

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, Alice Donkin, Sarah Angelina Acland, and Lorina Liddell (albumen print, 1860) Bodleian Library, MS. Photogr. b. 34, f. 137

In 1870 Miss Acland’s brother Herbert came down with scarlet fever, necessitating his withdrawal from Charterhouse, where he was at school with photographer-to-be, Henry Herschel Hay Cameron, “son of Mrs. Cameron (who photographs)” (as Mrs Acland put it).

Herbert’s quarantine lasted nine weeks, during which he chose to amuse himself with a ‘photographic apparatus’ given to him by his uncle — a gift no doubt partly influenced by his photographic schoolmate.

As fate would have it, Herbert would follow in the footsteps of Julia Margaret Cameron and her sons in more than photography. In 1876 he emigrated to Sri Lanka to become a coffee planter, as they had done. Tragically, he then contracted another often-fatal disease of the 19th century: typhoid. A year after arriving on the island he was dead, two years before Cameron also passed away there.

Taken or collected by Herbert Acland, Mrs and Mrs Richard J. Wylie, and Captain Collins, Pita Ratmalle Coffee Estate, Sri Lanka (albumen print, 1876 or 1877)

Bodleian Library, Ms. Photogr. c. 175

For Mrs Acland, the loss of Herbert proved a terminal blow, hastening her own death in 1878 from consumption (tuberculosis). As an only daughter, this left Sarah Angelina with the responsibility of managing her father’s busy house; a challenge all the greater because of her own struggle with ill-health, mental and physical.

However, it brought other opportunities, not least to be at the centre of a network of learned acquaintances, many of whom she would go on to photograph.

Theodore Acland: fighting cholera in Egypt

Before Miss Acland and her father met Haffkine, another family member would make a mark on the field of infectious diseases: Theodore Acland. The third of Miss Acland’s seven brothers, Theodore was the only one to go into medicine. His opportunity to contribute to his father’s former specialty arose in 1883, when cholera broke out, this time not in Oxford, but 2,200 miles away.

Theodore’s experience was gained in his capacity as Medical Superintendent to the Egyptian Military Cholera Hospital and Principal Medical Officer of the Egyptian Army. The Egyptian cholera epidemic of 1883 arose a year after the British conquest of Egypt. It threatened not just the health of the people, but also the stability of the new Anglo-Egyptian regime and British trade with India, due to the suspension of shipping at Egyptian ports.

Theodore was given responsibility for treating Egyptian troops in Cairo, for which he drew on the administrative example of his father, setting up a quarantine camp, obligating hand washing in ‘carbolic water’ (phenol), and implementing a system of detailed record keeping. In his own “Sketches of an Egyptian Cholera Hospital: A Personal Narrative” he describes the scenes in Cairo, lamentably familiar today.

There was an air of desolation about the place, the shops were shut, and the streets were almost deserted by their inhabitants … the general gloom found no relief in the universal topic of conversation, which was of cholera and of nothing but cholera.

The 1883 cholera killed more than 55,000 in Egypt, a number some attributed to the primitive state of the living conditions and health structures. Theodore, however, counselled against such ‘orientalist’ conclusions.

It may be said that the native sanitary conditions have been held up to unmerited ridicule

he wrote,

and that the organization of the Medical Department did not deserve such reproaches as have been cast at it.

Arab villages were more sanitary than many British slums, he argued, despite the greater challenge of the tropical heat:

we live in a glass house and can ill afford to throw stones.

Haffkine meets the Aclands

One of the outcomes of the Egyptian epidemic was that it led Robert Koch, who Theodore had met in Cairo, to identify the ‘comma bacteria’ as the causative agent of cholera. An attenuated form of this bacillus was the basis of Haffkine’s cholera vaccine, which he first deployed in field trials in the slums of Kolkata in 1894, inoculating over 42,000 people. The earliest record of Haffkine’s entry into the lives of the Acland family is found a year after these trials, during his brief return to England to recover from malaria.

Towards the end of her life, Miss Acland would explain the circumstances of her first meeting with Haffkine. In 1895, however, all her correspondence reveals is that she had written a short biographical memoir about him for Sir William Hunter, author of The Imperial Gazetteer of India. This achievement seems even to have surprised Haffkine, who later admitted

I cannot explain now how it was that you assimilated to that extent so many details of a career which had come so suddenly and accidentally your way.

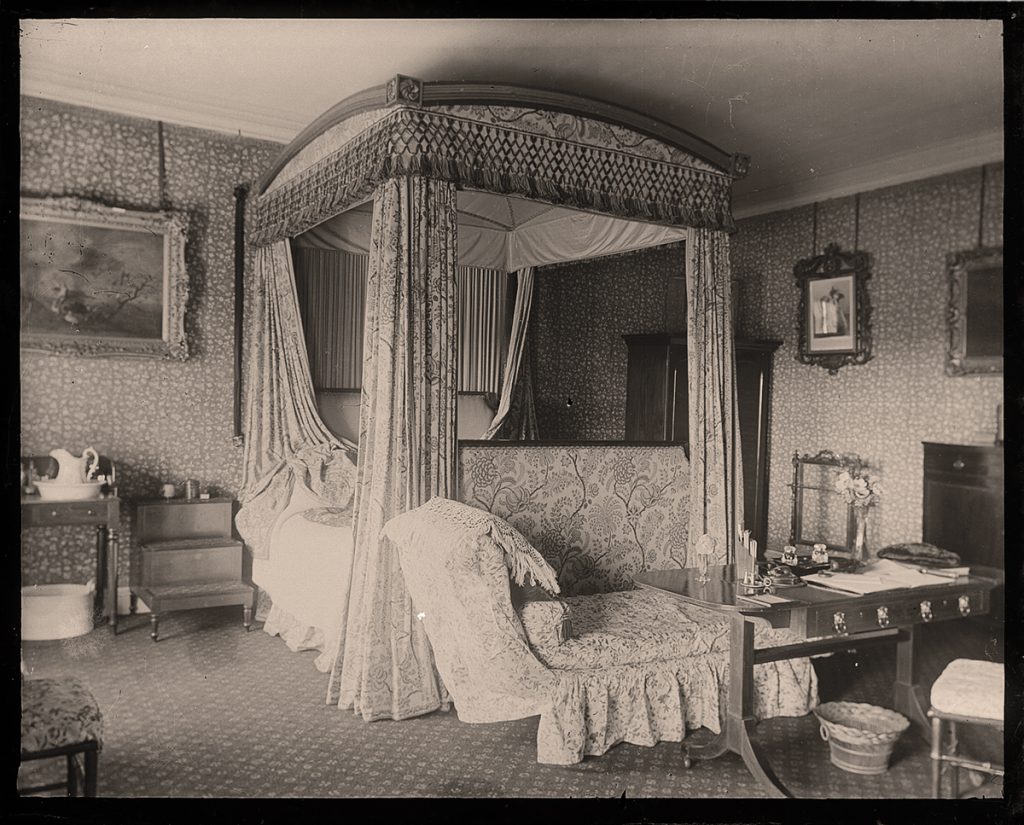

Miss Acland’s memoir was written in December 1895. In January more details emerge of Haffkine’s friendship with her father, after he was invited to stay at Killerton House, the Acland ancestral seat in Devon (now a National Trust property). At Killerton, Haffkine was introduced to the great and good of Devonshire politics and society, on whom he made an excellent impression.

He has won golden opinion from everyone here”

Acland wrote to Sarah Angelina, before adding his own assessment that Haffkine was

a man active in more good works of Science, Art, and sound duties, than any man I have ever known.

Sarah Angelina Acland, “Bedroom at Killerton” (digital positive from 5×4 negative, 1899)

Bodleian Library, Minn Collection Negative 199/9

In mid January 1896 Haffkine left Devon for India again, where he would start work on his new vaccine for bubonic plague (first tested, as was his habit, on himself). Three years would pass before he reappears in the lives of the Acland family, when, in May 1899, Miss Acland reported that he was back from his work amongst the plague and

is coming again to see us after he comes back from the Continent & I hope to be able to photograph him.

Sarah Acland: photographing friendship

Portraiture was the genre in which Miss Acland first established her reputation as a photographer. Most of her portraits were made in a daylight studio overlooking her garden in Broad Street. There many celebrities from art, science and politics sat for her, among them Prime Ministers Gladstone and Lord Salisbury, in portraits that would be exhibited at the Royal Photographic Society and published widely in the press.

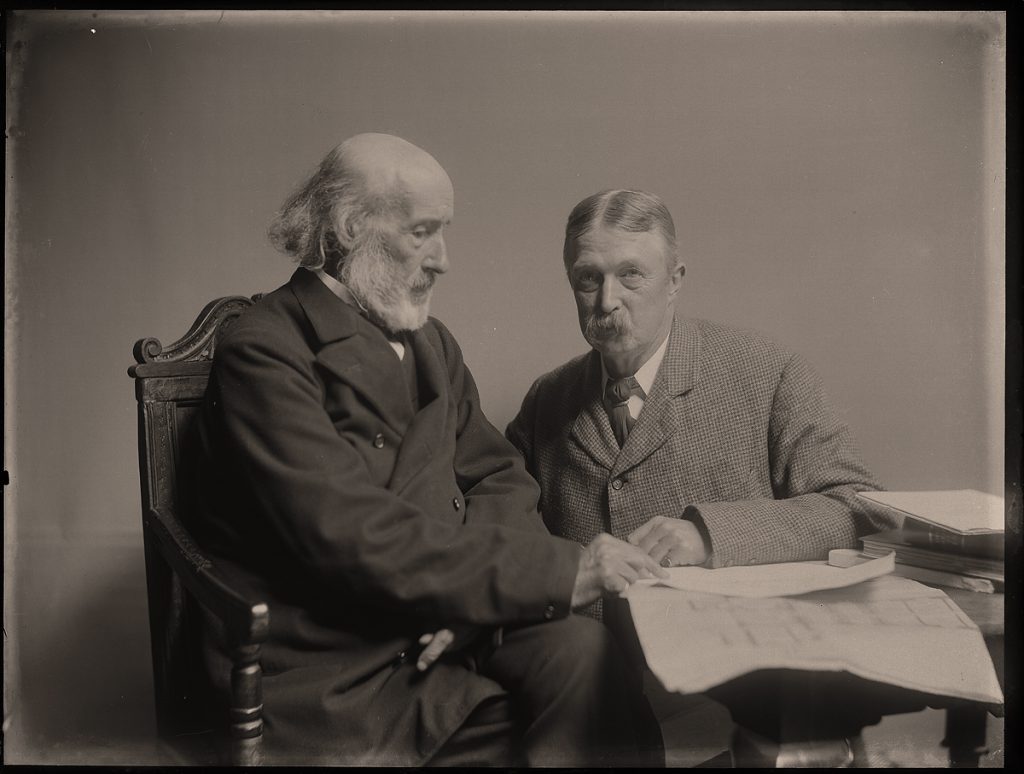

Unusually, Miss Acland’s portraits of Haffkine were made not in Broad Street, but at Boars Hill, outside Oxford, in a house she rented in summer 1899 to get out of the city. Three glass negatives of Haffkine survive, all half-plate in size, taken between 13 and 17 June 1899.

In the portraits, Haffkine, then aged 39, is seen dressed in wing collar, double-breasted jacket and trench coat. One image depicts him in profile, his striking features perfectly modelled against a dark background.

Sarah Angelina Acland, “Mr Mordecai Wolfgang Haffkine” (digital positive from half-plate negative, 1899) Bodleian Library, Minn Collection Negative 169/4

The others show him in conversation with the then aged Acland, holding a book and papers that presumably relate to cholera vaccines.

Sarah Angelina Acland, “Sir Henry Acland & Mr. M. W. Haffkine”

(digital positive from half-plate negative, 1899) Bodleian Library, Minn Collection Negative 202/9

Double portraits of this type were unusual in photography of the period, but were an approach Miss Acland favoured for her father’s closest friends.

Among her other ‘conversation pieces’ are studies of Acland with Friedrich Max Müller, who had assisted him during the Oxford cholera by obtaining intelligence about drainage systems in China;

Eleanor Smith, who organised the district nurses in Oxford for many years;

Sarah Angelina Acland, “Sir Henry Acland & Miss Smith” (digital positive from half-plate negative, c. 1895) Bodleian Library, Minn Collection Negative 202/6

and John Shaw Billings, first director of the New York Public Library, driving force behind the new Johns Hopkins Hospital building, and mastermind of the response to an epidemic of yellow fever that broke out in Tennessee in 1879.

Sarah Angelina Acland, Henry Acland and John Shaw Billings inspecting plans for the New York Public Library (digital positive from half-plate negative, 1898) Bodleian Library, Minn Collection Negative 138/2

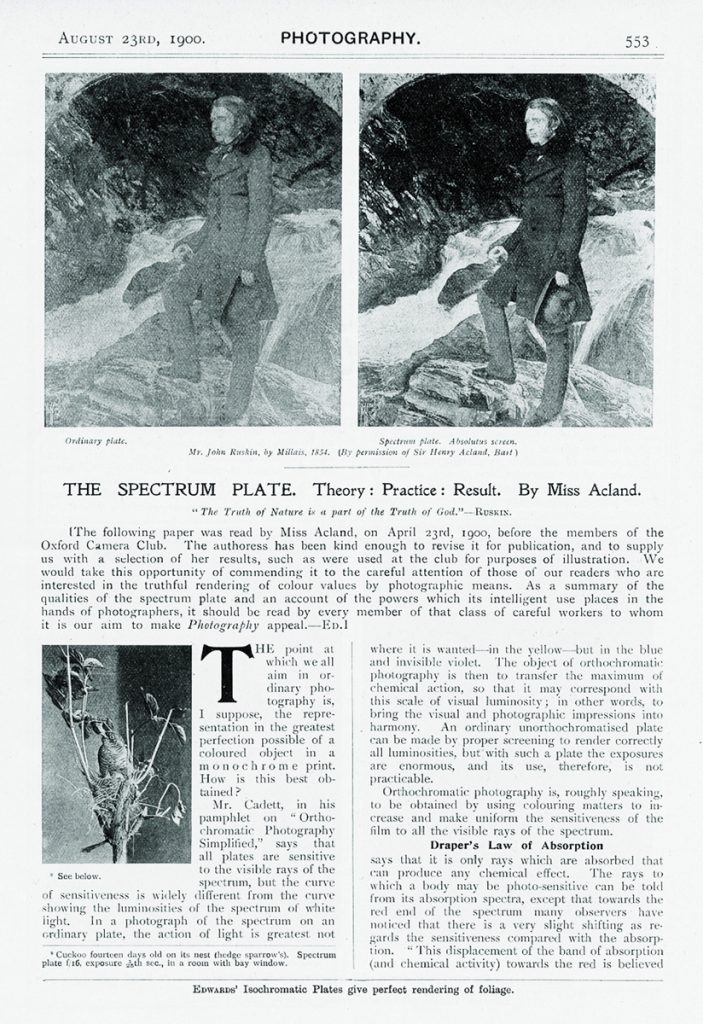

As well as a commemoration of friendship, Miss Acland’s portraits of Haffkine were part of a programme of experiments she conducted at Boars Hill on the capabilities of orthochromatic photographic plates — monochrome plates sensitive to the full range of colours, not just blue. This programme culminated in her giving a lecture (her second) to the Oxford Camera Club in April 1900. Entitled “The Spectrum Plate. Theory: Practice: Result”, it was also published as a paper in the journal Photography and as a stand-alone pamphlet.

Miss Acland, “The Spectrum Plate. Theory: Practice: Result”, Photography, no. 615, vol. 12 (23 Aug 1900), pp. 553 – 560, p. 553

After 1899, thirty years would pass before Miss Acland had Haffkine’s portraits printed for the copies that survive in the Museum’s collections. In the meantime both she and her subject experienced significant changes in their lives.

Sea change in a new century

In 1900 Sir Henry Acland died. The change was a huge upheaval for Miss Acland, requiring her to move out of her family home of 50 years, with the loss and freedom from the duty of supporting him that this entailed.

Haffkine, meanwhile, was faced with the fallout from the infected vial of his plague vaccine, which led to the death of 19 people in 1902. The cause of the infection was initially attributed to the use of heat rather than carbolic acid in the sterilization process for the vaccine, for which Haffkine, now denied Acland’s advocacy in government and the medical establishment, was officially blamed, until his eventual, albeit pyrrhic, exoneration in 1907.

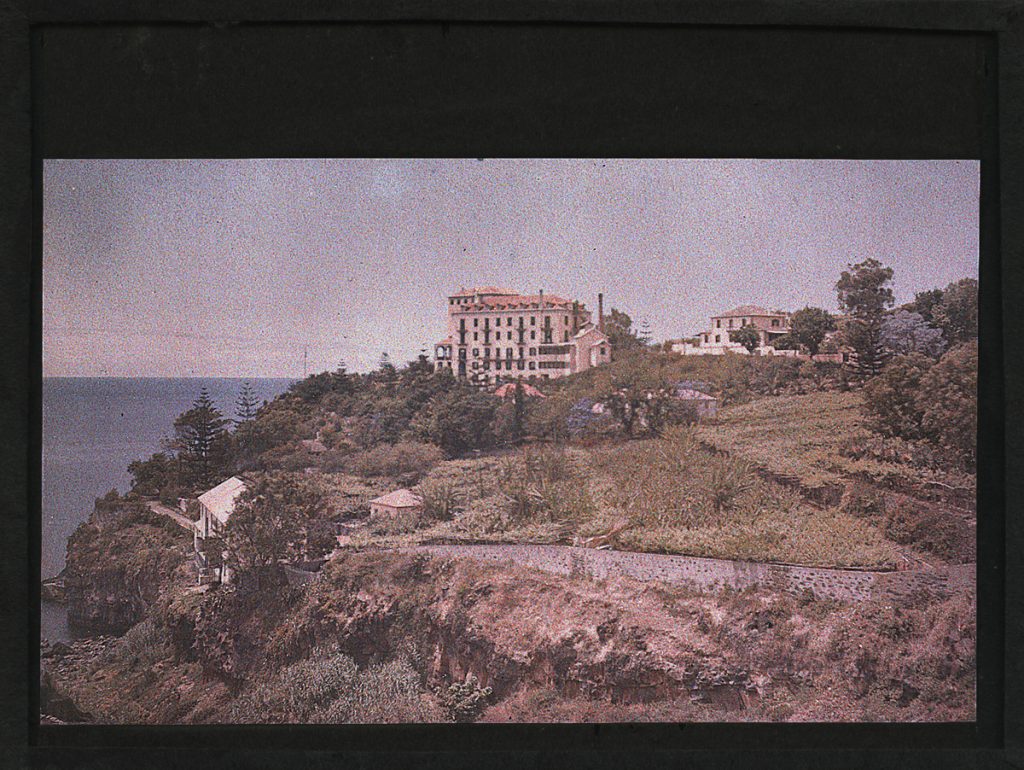

One of changes Miss Acland made after her father’s death was to spend winters away from Oxford in Madeira. From 1908 to 1915, she stayed in the luxury of Reid’s Palace in the capital Funchal, enjoying the warmth, luxurious gardens, and good light for colour photography that the Atlantic island provided.

Sarah Angelina Acland, Reid’s Palace Hotel, Funchal (autochrome, 1908?)

HSM, Inventory no. 19122

Experimentation and disease in Madeira

By 1908 Miss Acland was already famous in photographic circles as a pioneer of colour photography, having been one of the few amateurs to master the three-colour process. In Madeira she experimented with the newly-released Autochrome colour plates, as well as, as they became available, other ‘screen plate’ processes, such as Omnicolore and Paget plates.

In her first years on Madeira, Miss Acland achieved excellent results with the new colour systems, exhibiting such works as In a Madeira Garden and Study of Crimson Bougainvillaea, Madeira at the Royal Photographic Society. In 1910, however, on her third visit to Madeira, the first of two serious medical emergencies hit the island and set back her ability to progress photography significantly.

The emergency in question was an outbreak of typhoid at Reid’s Hotel.

The panic is intense and people are flying off at a tangent everywhere

she wrote to her brother. The disease hit visitors and staff badly, including Miss Acland’s own maid Mabel.

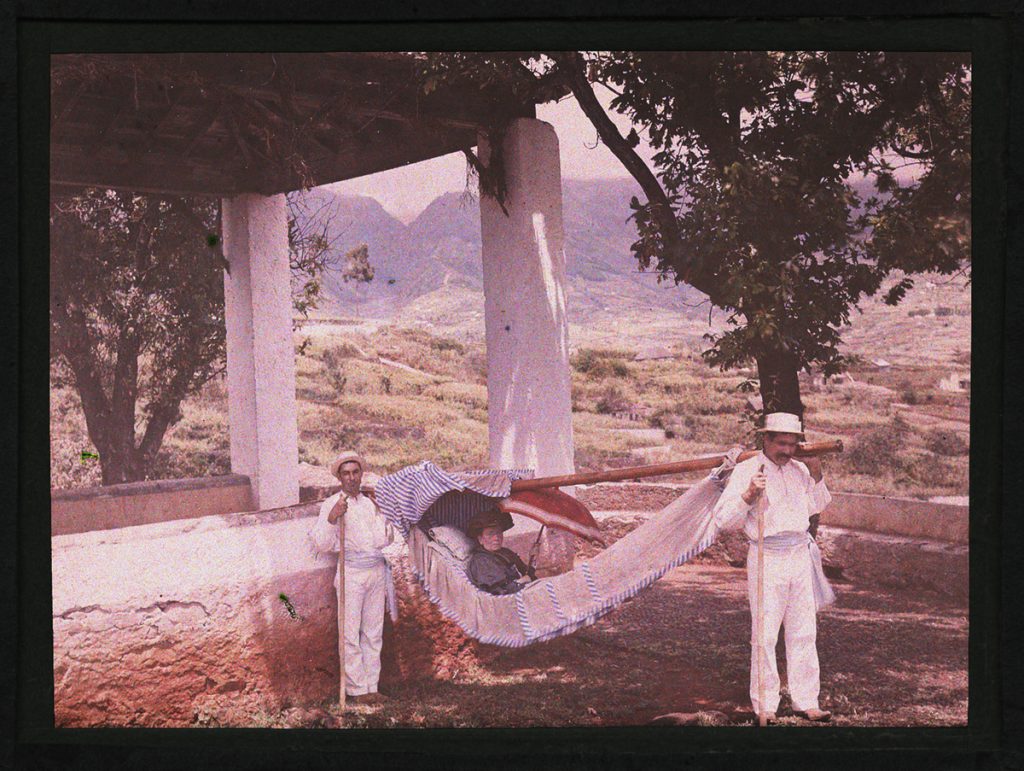

A maid or companion of Sarah Angelina Acland, Miss Acland in her hammock at the Capela da Nazaré, Funchal, Madiera (autochrome, 1912)

The hammock was a common mode of transport in Madeira. During the typhoid outbreak at Reid’s Hotel in 1910, Miss Acland’s hammock was used to ferry the sick to a temporary hospital in the Villa Victoria.

HSM, Inventory no. 17810

Mabel would recover after five weeks of high fever, as did Alice Wilson, the maid of the Spedden family, who a year later would also survive the sinking of the Titanic. Others were not so lucky, despite a vaccine against the Salmonella bacterium that caused typhoid already being available by the 1900s.

Emmeline Crocker, a horticulturalist out collecting specimens for Kew Gardens, for example, fell ill and died. So did the maid of a Mrs Cleveland Thomas, who, according to Miss Acland,

must have been a very bad woman

as she

would not allow the maid to see a doctor as she said that she brought her out to work & not to be ill.

During the typhoid Miss Acland sought advice from her two on-tap experts on infectious diseases, Theodore and Haffkine.

Haffkine counselled that

an outbreak in an Hotel of 50 to 60 typhoid cases, in 2000 residents, is a frightful incident, & should put the whole island on the black list.

He also suggested she consider Greece, Corfu or Tangiers for future years. Yet return to Madiera Miss Acland did — the wisdom of which was not without question given what then transpired.

No sooner had Miss Acland arrived back in Madiera in autumn 1910 than an epidemic of cholera broke out on the island. This time the contagioin spread throughout Funchal. Travel bans were put in place for the whole island, preventing steamers stopping.

We are rather like Napoleon on St. Helena

she commented, also reporting rioting in the streets against the sanitary measures.

While sitting out the cholera in Madiera one of Miss Acland’s occupations was learning to play the Portuguese guitarra.

Sarah Angelina Acland, Unknown woman playing a Portuguese guitarra (autochrome, 1911 or 1912?) HSM, Inventory no. 19113

The infection in Madeira, which represented the western extent of the 6th global cholera pandemic, raged for four months and led to 555 deaths from 1,774 cases. This time, however, Miss Acland took the challenge in her stride. She and her companions had become ‘accustomed’ to the measures in place, she wrote, including the policemen stationed at houses with infection.

During the cholera, Miss Acland again benefitted from support from her expert medical network. Haffkine, for example, sent his “Notes on the methods of mitigating the death-rate from cholera”, written in Simla in 1910, for her to convey to the relevant authorities. She also took the opportunity to visit the bacteriological laboratory in Funchal to see the cholera bacillus under the microscope, at the invitation of the English physician and her close friend, Dr Michael Comport Grabham.

Honouring Haffkine with a portrait

Miss Acland managed only two colour photographs over the winter of 1910-11 due to the cholera. In later years she would revive her photography with the help of her maids — newly inoculated against typhoid — until forced to end their visits to Madeira due to the onset of WWI. Back at home in Oxford, as well as continuing with photography, she also developed new interests.

One of these interests was to learn Russian. Always a strong linguist, her interest in Russian had been piqued when she took in two refugee women from Poland during the War. As well as begging Russian texts for her birthday, she enlisted the support of Haffkine in her new passion. Several letters from him in Cyrillic survive in her correspondence, which she practiced translating.

The conclusion to Miss Acland’s photographic career, and the culmination of her portrait project, came in 1930, when she arranged for a pair of presentation albums of her best work to be printed. One of the albums was given to the Bodleian. The other is now in the History of Science Museum and contains two beautiful carbon prints from her negatives of Haffkine.

In July 1930 Miss Acland annotated the portraits in her albums with reminiscences of the sitters. In the notes to the first portrait of Haffkine she related his history:

Mr. Mordecai Wolfgang Haffkine was born in Odessa in 1860 and went to Odessa University on leaving school in 1879.

Here he greatly distinguished himself.

As a Jew he was not allowed to take a Doctor’s degree but was thought so very highly of, that a special Laboratory was built for him.

From 1889 to 1893 he was assistant to M. Pasteur in Paris. He then went to India from 1893 to 1915 for bacteriological research work, and became a naturalized British subject.

Next to the second portrait of Haffkine, Miss Acland finally explained how she first came to know the vaccine pioneer.

It was somewhere in the 90s that my Father first met Mr. Haffkine in London.

My Father had gone up to hear Mr. Haffkine, the young bacteriologist assistant to Pasteur, lecture and was so much struck by him and his unassuming ways that he invited him to come and stay with us.

Sir William Hunter then living at Oaken Holt under Wytham Hill was also anxious to meet Mr. Haffkine and came to tea.

Dr. Dixey the present Bursar of Wadham had been showing our guest Oxford, and they were all talking when I drew attention to the fact that Mr. Haffkine had fainted.

He had a sharp attack of malaria. We put him to bed and nursed him and he has been a friend ever since. I heard from him for the New Year.

Three decades of friendship

Three months after writing these words, and 35 years after it began, the friendship between Miss Acland and Haffkine finally came to an end when he passed away in Lausanne on 26 October 1930, aged 70.

Miss Acland died of old age in Oxford five weeks later, in her 82nd year, having survived, at close quarters, the threat of scarlet fever, typhoid and two cholera pandemics.

Sources

Joel Gunter and Vikas Pandey, “Waldemar Haffkine: The vaccine pioneer the world forgot”, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-55050012 (published 11 Dec 2020, accessed 29 Jan 2021)

Christopher Rose, “A Tale of Two Contagions: Science, Imperialism, and the 1883 Cholera in Egypt” https://islamiclaw.blog/2020/05/25/christopher-s-rose/ (published 25 May 2020, accessed 29 Jan 2021)

Henry Wentworth Acland, Memoir on the Cholera at Oxford, in the Year 1854 (London, 1856) (https://archive.org/details/39002086311736.med.yale.edu/page/n7/mode/2up)

Theodore Dyke Acland, “Sketches of an Egyptian Cholera Hospital: A Personal Narrative”, St. Thomas’s Hospital Reports, New Series, vol. 13 (1884), pp. 257-276 (https://archive.org/details/stthomasshospita13stth/page/257/mode/2up)

J. B. Atlay, Sir Henry Wentworth Acland, Bart. (London, 1903) (https://archive.org/details/b31355377/page/n7/mode/2up)

Bodleian Library, Ms. Acland d. 42 (Correspondence of Sarah Acland to William Allison Dyke Acland, c. 1858-75)

Bodleian Library, Ms. Acland d. 108 (Correspondence of Sarah Angelina Acland to William Allison Dyke Acland, c. 1894-1904)

Bodleian Library, Ms. Acland d. 110 (Correspondence of Sarah Angelina Acland to William Allison Dyke Acland, c. 1909-11)

Bodleian Library, Ms. Acland d. 134 (Correspondence of Henry Wentworth Acland to Sarah Angelina Acland, c. 1895-96)

Bodleian Library, Ms. Eng. Misc. d. 214 (Sarah Angelina Acland, “Memories in my 81st year” [1930])

Bodleian Library, Minn Collection negs. 169/4, 202/8 and 202/9 (half-plate glass negatives of portraits of Waldemar Mordechai Haffkine by Sarah Angelina Acland, June 1899)

History of Science Museum, Ms. Museum 417 (Sarah Angelina Acland, “Photographs taken in my old home in Broad Street Oxford, between the years, 1891-1900, with annotations made in 1930 in my 81st year”) (album of carbon prints printed by Henry Minn)