Death at The Farm – (Re-)visiting Harry on Gallipoli

Our current special exhibition, ‘Dear Harry…‘, presents an intimate portrait of Henry Moseley, a brilliant British physicist who was killed, aged 27, in World War I in Gallipoli, Turkey on 10 August 1915. To mark the exhibition and the centenary of the Dardanelles campaign, our director Dr Silke Ackermann embarked on a pilgrimage to Gallipoli and retraced some of Harry’s final steps.

By Silke Ackermann

View from Chunuk Bair across the gullies towards the landing beaches in the distance

The first thing that strikes you is the serene beauty of the place. Turquoise waters, shady woods, and the flowers – so many flowers, blood-red poppies amongst them. And then it strikes you that Harry, who loved his cottage garden so much, would never have seen it like this. When he first landed at Helles at the southern-most tip of Gallipoli the landscape already showed the brutal scars of months of heavy fighting. When he returned as part of the infamous August offensive, the last few days of his life were spent in chaos and turmoil.

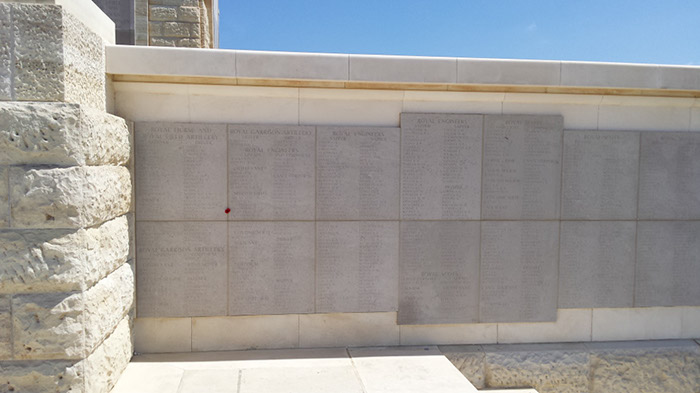

Following the opening of our exhibition I have come to Gallipoli to find Harry, or at least trace his last footsteps. Like so many others, his body was never identified and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website states that his name is on Helles Memorial, one of the countless memorials for soldiers of all sides. ‘Panels 23 to 25 or 325 to 328’, the website states somewhat enigmatically. What on earth does that mean? Don’t they know exactly?

When I get there in the midday heat (and it is only late May, what must it have been like in August?!) I start looking for Harry. With a jolt his name suddenly jumps out to me, in the middle of panel 24, looking out into the calm waters. The panels are organised by division, then by rank, not by name. So Harry is amongst the Second Lieutenants of the Royal Engineers, name upon name over seven panels in two different positions on the vast memorial.

Helles memorial, panels 23 to 25. Harry’s name on panel 24 is marked by a poppy.

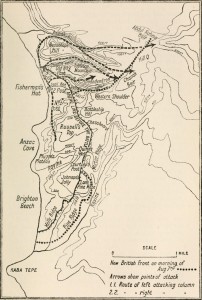

But he didn’t die here, that we know for sure. So I retrace my steps and with the help of my excellent guide Seyhan return to the landing beaches on the western side of the peninsula. We get out of the car at every possible point. ‘Embarkation Pier’? Or ‘Anzac Cove’? Or maybe ‘Suvla Point, the most northerly of the possible spots? The available information is patchy, so we stop at every one of them and look up across the shrubbery to the point Harry and his comrades were meant to take: Hill Q, near the much better known Chunuk Bair.

I had intended to climb up through the gullies as Harry would have done, but the snakes prevent that. So we drive up to Chunuk Bair and walk down the steep 400 metres or so to an area known as ‘The Farm’. ‘The Farm’ is the least visited of the many cemeteries on Gallipoli, Seyhan tells me, and I soon understand why. We slip several times on the pine needles, and soon we sweat profusely. Unfamiliar sounds all around us. What must it have been like in the August heat, where every crack could have meant death?

When we finally get to the cemetery I am struck by how peaceful it seems. There is a surprisingly small number, just seven gravestones, all of rather senior officers, all ‘believed to be buried’ here. But in this small area of about 30×60 metres there lie 652 British soldiers, 634 of whom remained unidentified. It is to here that Harry and his men retreated after the failed attempt to take Hill Q on 9 August; it is here that heavy hand-to-hand fighting ensued on the following morning; and it is likely here, or close by, that Harry died. He may well be one of those lying here, never identified.

The Farm cemetery

And it is here that the thought hits you full on – what a loss to humanity, all those young men from both sides, all those mothers and sisters, not just Harry’s, mourning the loss of a loved one, with nothing gained whatsoever.

On the way back up the hill Seyhan bends down and hands me a small grey marble-like object. It is a piece of shrapnel. Even after 100 years the area is still littered with it.

Around these oddball figures, we weaved the legend of the homunculus. This artificially-made miniature man was said to have been created by the alchemist Paracelsus, and appeared in various guises in alchemical texts – sometimes he was thought of as a spiritual being, who would reveal some secret knowledge to its maker. Perhaps the putti in the painting are themselves homunculi?

Around these oddball figures, we weaved the legend of the homunculus. This artificially-made miniature man was said to have been created by the alchemist Paracelsus, and appeared in various guises in alchemical texts – sometimes he was thought of as a spiritual being, who would reveal some secret knowledge to its maker. Perhaps the putti in the painting are themselves homunculi?