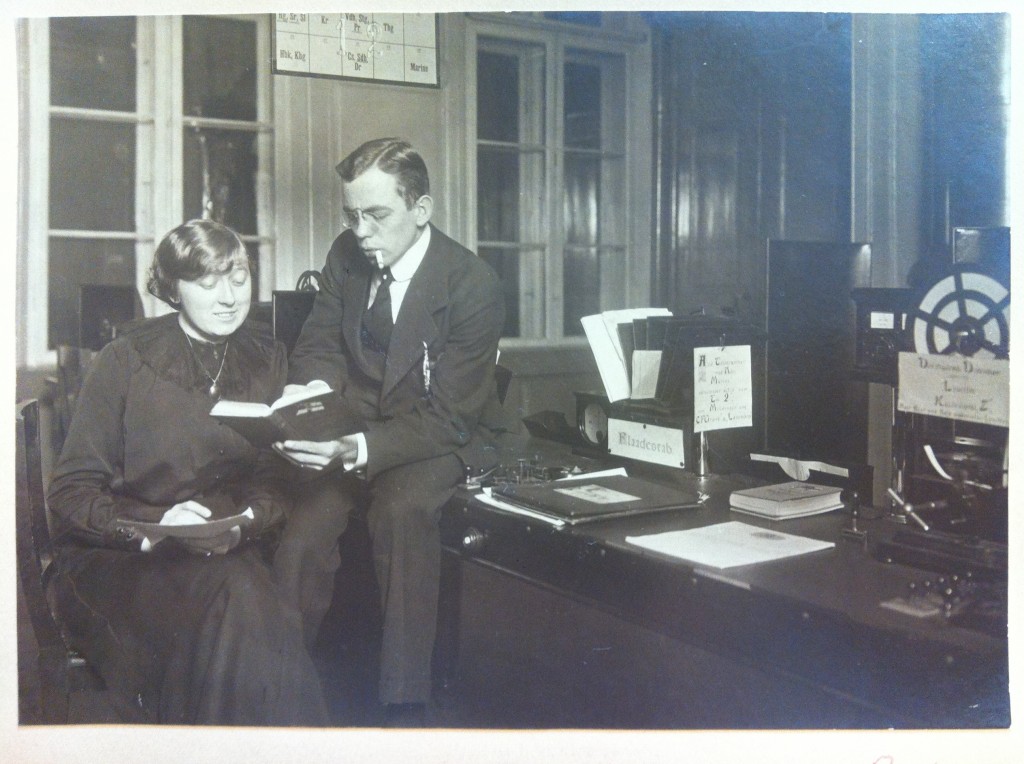

Two young telegraphers at the Main Telegraph Station in Copenhagen, Miss Galschiøtt and Mr. Henriksen, aiding a secret military intelligence unit called Kystcentralen, circa 1915. Post & Tele Museum, Copenhagen.

On June 1, 1918, ten “ladies” with “excellent language skills” had their first day of work as telegram censors at the Danish state telegraph. They had all been tested in foreign languages – German, French and English – by a professor at the University of Copenhagen, and all of them were quite literally daughters of the elite. The first two names on the list of employees are illuminating: “Miss INGER GRAM, daughter of the Supreme Court President, Dr. Jur. R.S. Gram”, followed by “Miss ASTRID HERTZ, daughter of the Medical Officer, Dr. Med. Poul Hertz.”

Inger Gram and Astrid Hertz, and their eight, equally unmarried colleagues, were employed by the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs but their office was located at the Main Telegraph Station in Copenhagen. Here, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had a unit for cable censorship, which had been in operation since November 1916. In fact, the system of censorship and secret monitoring had been up and running since August 1, 1914, when the Telegraph Directory decreed that no telegrams transmitted from Denmark should contain “sensational and false messages about Danish conditions and popular moods“. However, the system was loosely organized in the beginning of the war, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was anything but satisfied with the practical handling of censorship issues, which initially sorted under the Telegraph Directory and the so-called Ministry for Public Works. Accordingly, after a harsh debate in the Danish parliament, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs took charge of the surveillance system and established its own Censorship Office at the Main Telegraph Station, which was staffed by four external censors who had no previous connections to the Danish State Telegraph.

Yet the system remained inefficient and defective. The Ministry of Foreign Affair’s censorship director, Marinus Yde, complained in a memo to his superiors that merely 500-600 telegrams, out of the approximately 7 000 telegrams that the Danish State Telegraph transmitted on a daily basis, were handed over to his censors. Thus, there was clear lack of cooperation between the censors and the ordinary telegraph staff. In another memo, dated to 29 April 1918, Mr. Yde bemoaned this glitch in the system in a rather candid tone:

The whole mountain of telegram correspondence is thus being processed without any other control than that which is carried out by the (often very young) telegraph operators, while they are transmitting and charging the telegrams. This kind of control is of no value at all.

This is where Miss Inger Gram and her nine female colleagues entered the picture. They were definitely not the first women within the Danish telecommunications sector. The first female telegraph operator in the country, the famous author and feminist Mathilde Fibiger, had entered service as early as in 1863, and there had been women working for the Censorship Office before the summer of 1918, for instance as stenographers and record keepers. Yet the idea of employing women as cable censors was a novelty of World War One – and its origin was seemingly Swedish. In the above-mentioned 1918 memo, Mr Yde wrote about an excursion to the Main Telegraph Station in Stockholm, where female censor clerks functioned as a kind of basic control filter, by “sifting” the “whole mountain” of incoming and outgoing telegrams. And whenever they discovered a suspicious message, it was forwarded to senior (male) censors in a neighboring office.

Mr. Yde was greatly impressed by this model and recommended it with enthusiasm to his superiors. The gender aspect was explicitly highlighted: “The main work could definitely be carried out by female employees, who would be provided by the State Telegraph, thereby keeping the expenses at a minimum.” As the quotation makes clear, there was a financial dimension to the employment of female censors: qualified women with the necessary language skills were far less expensive to keep on the pay-roll than equally qualified men.

Electric transporter, anno 1917, carrying telegrams between the departments at the Main Telegraph Station in Copenhagen. In the background, busy female operators are typing on their Morse apparatuses. Post & Tele Museum, Copenhagen.

So, the Censorship Office was re-organized yet again and it assumed a bicameral structure. The original censorship unit at the Main Telegraph Station was supplemented with an extra department called the Control Office, where the staff was made up by the ten language-skilled “ladies” (damer) and one man: a young PhD in philosophy named Kort Kristian Kortsen, who was affiliated with the University of Copenhagen. As in the case of the Swedish surveillance system, the mission of this office was to “carry out the preliminary, crude assessment of the massive load of telegrams, and put all those telegrams aside, that calls for a closer inspection by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ current censors.” This kind of surveillance work was labelled “control” (kontrol), whereas the senior office dealt with something called “prohibitive censorship” (prohibitiv censur).

Both offices were managed by an Official from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs named Lauritz Larsen, who was considered to be equipped with “exactly that interest for general patterns and small details, which is necessary for the perfect overall result.” To speed up the process and reduce the number of customer complaints, the offices were connected through a logistical device called an “electric transporter”: a cart that ran on rails in the ceiling with telegrams, censorship minutes and other kinds of messages. Yet the friction between the censors and the cable station staff remained an unresolved issue, and the system continued to be haunted by delays, misunderstandings and direct conflicts, but that is another story for another day.

Andreas Marklund is Researcher and Research Coordinator at Post & Tele Museum in Copenhagen, Denmark.