By Dr Elizabeth Bruton

Military communications in World War One evolved to meet new battlefield and military challenges during this period. Battles were won and lost on the strength of an army’s ability to communicate on the battlefield. New and old systems of communications were used side-by-side and interchangeably.

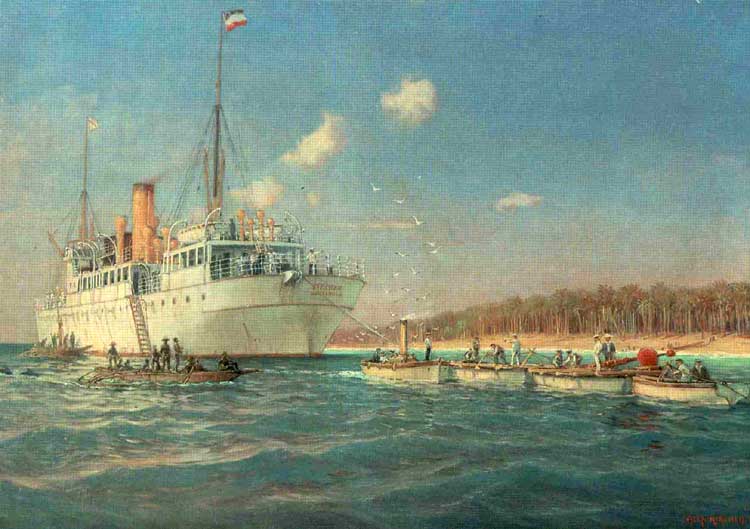

This was as much true of early battles on what became known as the Western Front as well as later battle such as the Battle of Passchendaele (also known as the Third Battle of Ypres) which took place from 31 July through to 1o November 1917. The Allied plan was for French, Belgium, and British troops as well as those from the British empire including Australians, Canadians, Indians, New Zealanders, and South Africans to take the high ground (ridge) south and east of the city of Ypres. The Battle of Passchendaele is of particular interest not because it was the site of any particular telecommunications innovations but rather because signalling failures contributed to the ultimate failure of the Allied attack and secondly because the battle is representative of signalling practice and operations at this stage of the war.

IWM Q 6050 Battle of Poelcappelle. Royal Engineers taking drums of telephone wire along a duckboard path up to the front between Pilckem and Langemarck, 10 October 1917. Image available in the public domain via IWM.

Communications failures occurred at both the First and Second Battle of Passchendaele. During the early stages of the First Battle of Passchendaele on 12 October 1917, the two lead British commanders Douglas Haig and Herbert Plumer believed – due to delays in communication and misleading information – that the advance had been successful and were unaware that the German counter-attack in the afternoon had wiped almost all of the Allied advance. Of particular problem was terrain in the area around Passchendaele as well as Ypres and Messines which was unsuitable terrain for laying cables. Furthermore, the ground had been heavily bombarded by German artillery as well as intense rainfall in the weeks leading up to the attack. At the Second Battle of Passchendaele which took place between 26 October and 10 November 1917, the retreat of the 4th Canadian Division from Decline Copse was due to communication failures between the Canadian and Australian units to the south as well as German counterattacks.

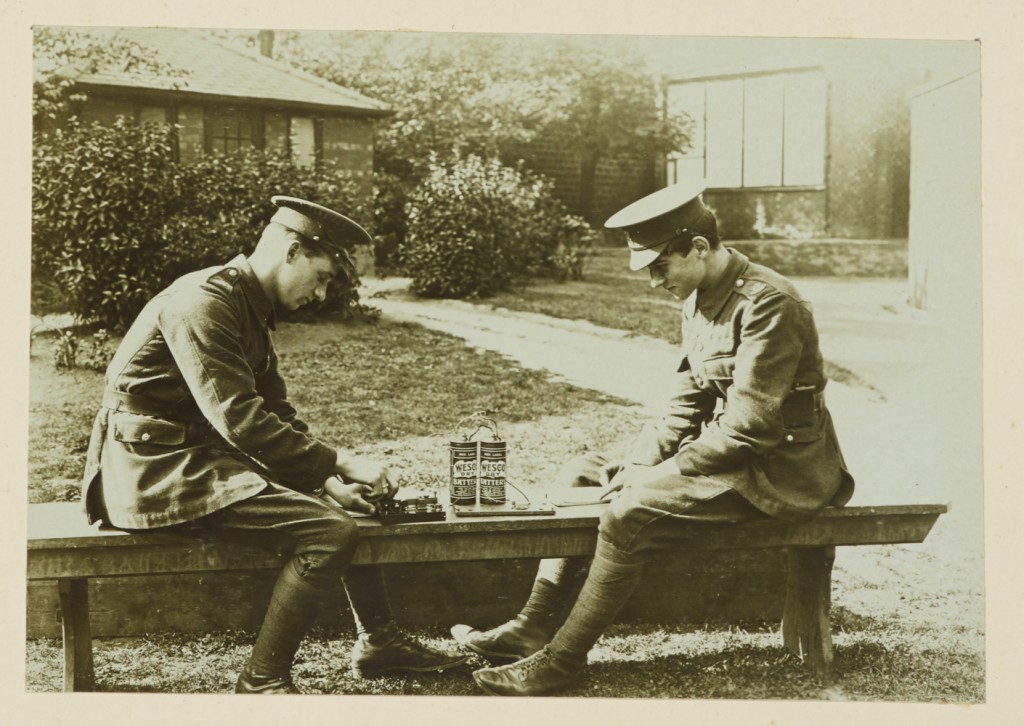

The British Army commonly used telegraph cables and telephones on the Western Front to communicate between the front line soldiers and commanders. But heavy artillery (gun) bombardment meant these lines of communications were easily broken. These lines of communications were also easily intercepted by the German army, as were the very basic wireless telegraph sets used by the British Army. Despite this, the speed of telephone and telegraph communication meant they were the most commonly used telecommunications systems used by the British Army.

Ruins as telephone posts by Le Section Photographique de L’Armee Francaise, n.d. Image available in the public domain.

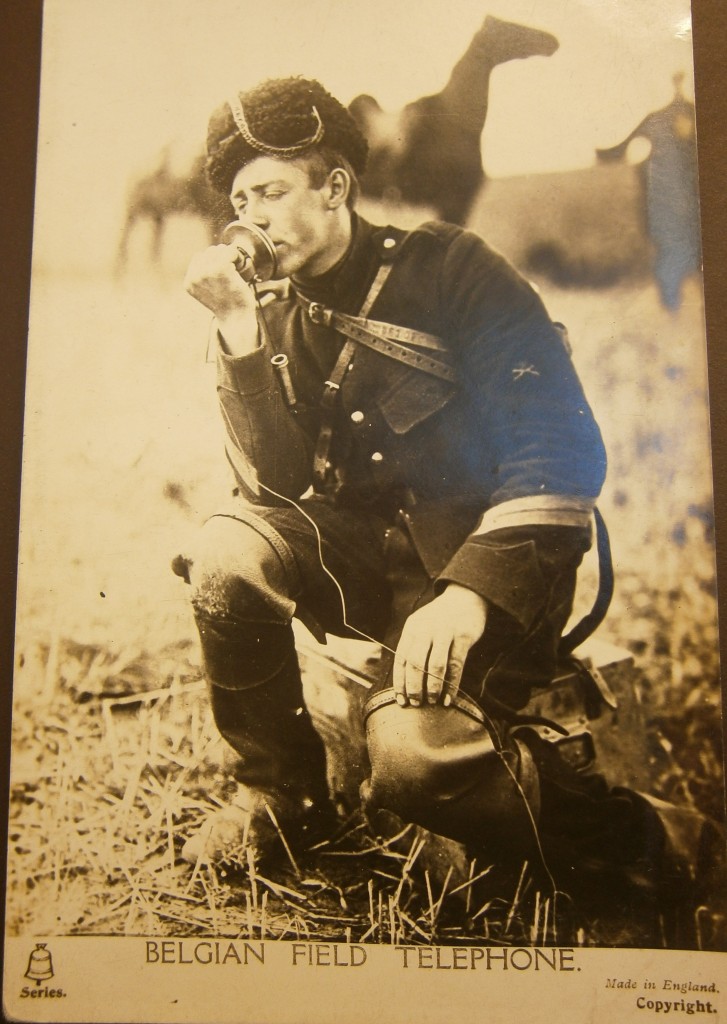

As a brief aside, these two evocative of photographs of field telephony in the war representing life more generally on the front were reproduced in various publications including printed periodicals such as War Illustrated News as well as postcards. These two particular photographs were kindly provided Dr Kate MacDonald from Postcards box GB9 – WW1: Postcards of life at the Front in the John Johnson Collection of Printed Ephemera held by the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. The former postcard of Ruins as telephone posts was produced by Newspaper Illustrations in England and credited as an official photograph of Le Section Photographique de L’Armee Francaise.

IWM Q6230 Carrier pigeons: A bus converted into a mobile pigeon loft on the Western Front, July 1916. Image available in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons and IWM.

Hence alternative methods of communication were required until (so the plan went) the higher ground was taken where cables could be used. Problems with these alternative methods of communications including carrier pigeons being hindered by high wind and messenger dog handlers becoming casualties were in part the cause for the misplaced belief by Haig and Plumer that the initial stages of the attack were successful.

More generally from 1915 onwards, non-telecommunications systems of signalling were used in parallel with and as a backup to telegraph and telephones. The British Army was forced to adapt, using older forms of communication such as carrier pigeons and written messages delivered by runners and messenger dogs to keep the lines of communications open. Messenger runners had one of the most dangerous jobs in the war having to run across open ground and risk being shot by snipers in order to make sure a message was delivered. Signalling flags were also used but could be only used in the daytime but were easily visible to the enemy.

Tactically, it was around the time of the Battle of Passchendaele that the German Army switched tactics and began to use “defence in depth”, that is delaying rather than preventing an enemy attack with the hope that the enemy would lose momentum as they cover an increasingly larger area. This had an impact upon signalling: Allied forward signal parties frequently became involved in the fighting and the larger areas covered by the Allies as a result of this tactic required artillery stations to be moved necessitating the improvisation of a fresh series of artillery signal communications.

Art.IWM ART 2920 BE2c aircraft of the Royal Flying Corps fly above the clouds amidst the small puffs of artillery fire. A small section of the landscape is visible far below the cloud line (1920). Image available in the public domain via the IWM.

During the war, aeroplanes developed rapidly from kite-like aeroplanes where pilots shot at each other with small guns to bombers and fighter planes. As the aeroplanes developed during the war, so did their means of communications. At the start of the war, pilots communicated using visual signalling such as rocking their wings and flags. By the time of the Battle of Passchendaele in late 1917, aircraft were commonly used for reconnaissance and long-range artillery spotting. Indeed by this stage of the war, most artillery spotting was done by aircraft using wireless communications: pilots communicating wirelessly with artillery stations on the ground, correcting the aims of British guns firing beyond the “line of sight” (what they could see) to German targets. Wireless communication was achieved using a mixture of radio telephony (voice over wireless) and wireless telegraphy (Morse code over wireless).

For example, on 12 October 1917 – the day of the First Battle of Passchendaele – there were one hundred and twenty-four zone (ranging) calls to the artillery for fire on active batteries, troops, transport, and machine-gun posts. Source: Jones, H. A. The War in the Air, Being the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force Volume 4 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1934), 206. By the end of the war, pilots were equipped with radio telephony (voice over radio) and were able to communicate over short distances with other aeroplanes and over longer distances with ground wireless stations.

National Library of New Zealand 1/2-012945-G Unidentified New Zealand World War 1 signaller on a German dug-out, Gallipoli Farm, Belgium, 12 October 1917. Photograph taken by Henry Armytage Sanders. Image available in the public domain via the National Library of New Zealand.

To conclude, the Battle of Passchendaele was not the site of any particular telecommunications innovation and indeed the lack of British success was in part due to communications problem. The landscape did cause some limitations in terms of problems laying cables but otherwise it was representative of telecommunications operations at the time: old and new signalling systems being used adjacent and interchangeably. By late 1917, wireless communication in aircraft was commonly used for co-ordinating artillery and this was very much the case at the Battle of Passchendaele in mid- to late-1917.

Sources and Further Reading

BBC iPlayer – The Great War Interviews – 8. John Willis Palmer (recommended by Graeme Gooday)

http://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/p01td2np/the-great-war-interviews-8-john-willis-palmer#group=p01tbj6p

John Willis Palmer, a Signaller with the Royal Field Artillery, recalls how the mud and fatigue at Passchendaele broke his spirit.

IWM Podcast 31: Passchendaele by Kate Clements

http://www.iwm.org.uk/history/podcasts/voices-of-the-first-world-war/podcast-31-passchendaele

Jones, H. A. The War in the Air, Being the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force Volume 4 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1934).

Internet archive: https://archive.org/stream/warinairbeingsto04rale

Priestley, R.E. The Signal Service in the European War of 1914-1918 (France) (Chatham: W. & J. Mackay & Co. Limited, 1921).

Internet Archive: https://archive.org/stream/signalserviceine00prie

Wikipedia: Battle of Passchendaele

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Passchendaele

About the author: Dr Elizabeth Bruton is a historian of science specialising in history of communications and former postdoctoral researcher for “Innovating in Combat”. See her Academia.edu profile for further details.