Charles Boyle’s Story

Orrery, by Thomas Wright, c. 1731 (Inv. 35757) It is thought that this orrery was owned by Charles Boyle. It is kept in the basement of the Museum, come see it when you next visit!

Name: Charles Boyle, Fourth Earl of Orrery

Dates: 1674-1731

Occupation: Politician

Object: Orrery, by Thomas Wright, London, c. 1731 (Inv. 35757)

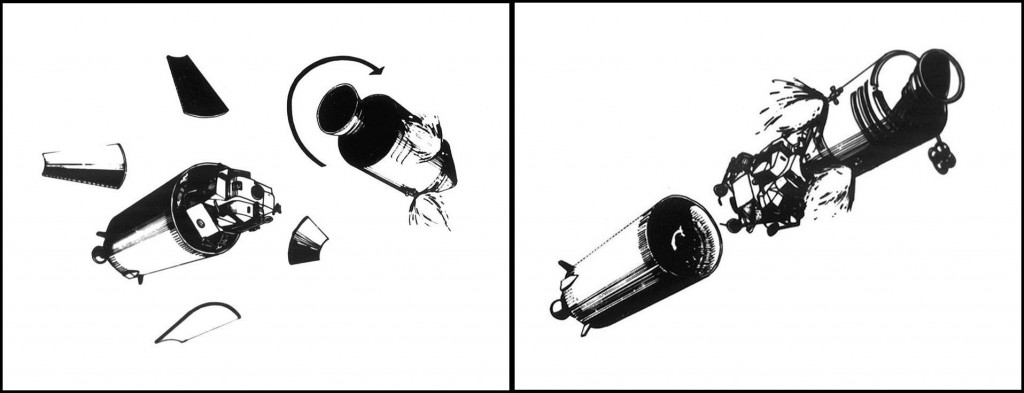

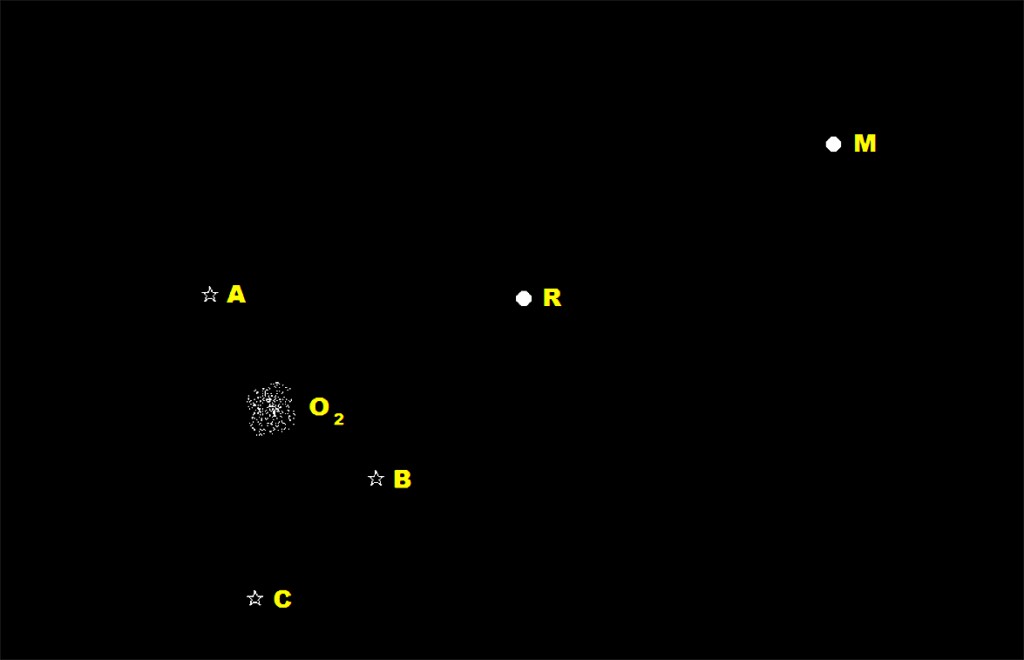

Story: The importance of Charles Boyle, Fourth Earl of Orrery, in the history of science is perhaps most simply captured by his name and his title. His surname – Boyle – points to his relation to the esteemed seventeenth-century natural philosopher Robert Boyle, who is associated with the air pump. His title – Earl of Orrery – points to his own contributions to science and natural philosophy, which were so widely recognised that the orrery, an astronomical device used to model the solar system and pictured above, was named after him.

Born to nobility in 1674, Charles Boyle was raised in a household that valued science and learning. He graduated from Christ Church, Oxford in 1694, before launching his career in the army and as a statesman. Until 1699 he served as a representative in the Irish Parliament and later became a M.P. for Huntingdon.

Gregorian Reflecting Telescope with Stand, c. 1710 (Inv. 20020). This object is one of many within the Orrery Collection at the Museum.

Professionally, Boyle was firmly a statesman: he performed no seminal experiments, and he has no scientific discoveries to his name. What made Boyle an amateur scientist, therefore, had less to do with the things he did and more to do with the things he had – his collection of scientific instruments ranked among the finest in England. The collection included everything from glass specimens for use with a microscope to Gregorian reflecting telescopes, and Boyle, driven by a deep personal interest in the sciences, went great lengths in amassing and tending to the collection. As a result of his success as an amateur collector, Boyle was named a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1706.

Along with science, Boyle also pursued writing and even published a play called As You Find It. During his eventful life Boyle was, for a short time, imprisoned in the Tower of London in 1722 as he was suspected of treason and being apart of the Jacobite Atterbury Plot. However, no evidence was found and he was released on bail before being discharged.

Boyle is highly representative of scientific amateurs of his time, most of whom came from backgrounds of wealth and nobility, only dabbling in science and natural philosophy of out of personal interest. Even among amateurs, scientific activities during this time were predominantly confined to those with ample time and resources at their disposal. Boyle serves as a good starting point for understanding how the status of the amateur scientist became available to wider segments of the population over the following centuries.

By Andrew Lea