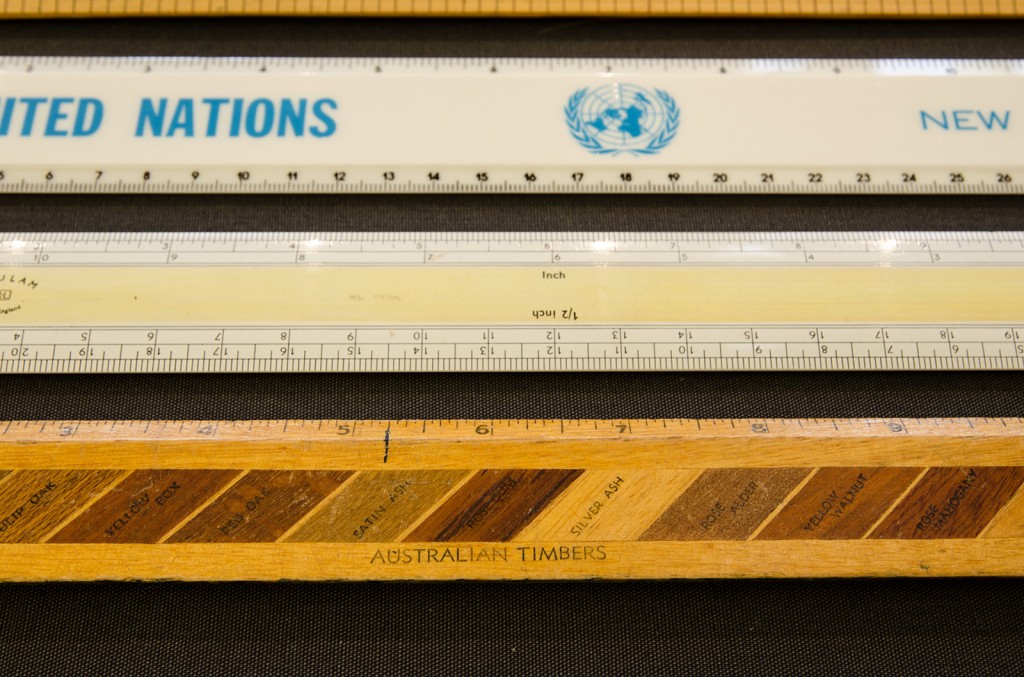

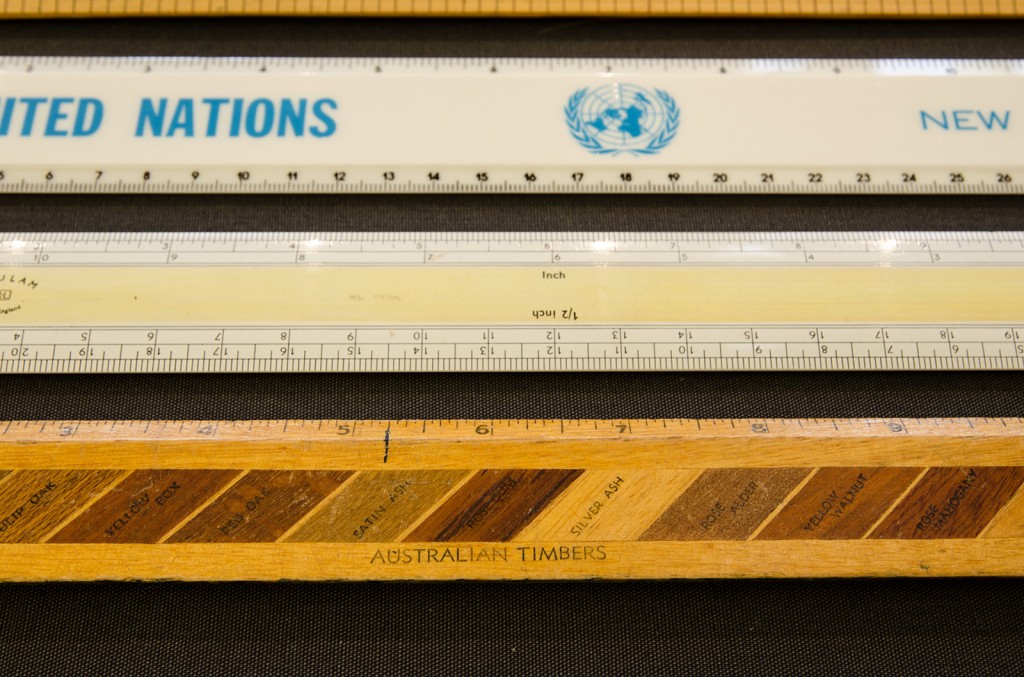

Rulers from the collection of Arthur Whillock (1912-2006), inv. 13436

Many of us are hoarders. We collect objects with a common theme, scoop up shiny trinkets that catch our eye, or just plain refuse to throw old stuff away. As the years pass, all these things accrue, on shelves, or tucked into nooks, crannies and cupboards.

Gathering collections for museums is not always dissimilar; museum collections tend, over time, to expand much more than they contract. Naturally, people who work in museums are, on the whole, the sort of people who like to collect and store objects. It can be hard to resist a new addition to the collection when something becomes available, either at an auction or through a donation.

Items can come from a variety of sources, including dealers and auctions. Sometimes individual objects are received, but often a group or collection is offered as a whole. What’s New?, the temporary exhibition in our Entrance Gallery (11 June – 22 September 2013), shows a selection of objects from three collections that were recently donated as gifts to the Museum’s collection.

Trotter Pattern Portable Photometer, by Everett Edgcumbe, c.1910; inv. 13422

Unlike hoarding at home, there is a formality to the process of accepting items into a museum’s collection. This process is called accessioning, and every object that becomes part of a collection must be accessioned. The process may vary across institutions but generally involves checking an item’s suitability for the collection, its provenance (including legality), its condition, and any safety concerns from a materials point of view. If accepted, this information is entered with the object’s record into the collection database and it is assigned a unique inventory number.

Once accessioned, an object falls under the museum’s duty of care in perpetuity. For this reason, the acceptance of new material has to be considered seriously – sadly we have neither the space nor the money to take everything we fancy!

So, what’s new?

Large Dial Ammeter, by Electric Construction Company, Wolverhampton, ?1960s; inv. 13408

The exhibition includes a selection of science equipment used for teaching in the mid-20th century, donated by Headington School, an independent school for girls in Oxford. Two large electrical meters – an ammeter and voltmeter – were evidently used to display the effects of experiments to the class. The meters were produced by the Electric Construction Company, a major British electric supplier for much of the 20th century. The school’s collection also includes a thermopile – a brass cone-shaped device that can detect heat at a distance – and a Geissler tube, which lights up when a high voltage is applied to the electrodes at each end.

Gyroscope by Newton & Co, London, c. 1905; inv. 13293

Another collection represented in the exhibition was donated by the University of Oxford’s Department of Engineering Science. It features a handsome brass gyroscope, dating from around 1905, and a photometer from around 1910, designed by Alexander Trotter, then a leading practitioner in the measurement of illumination.

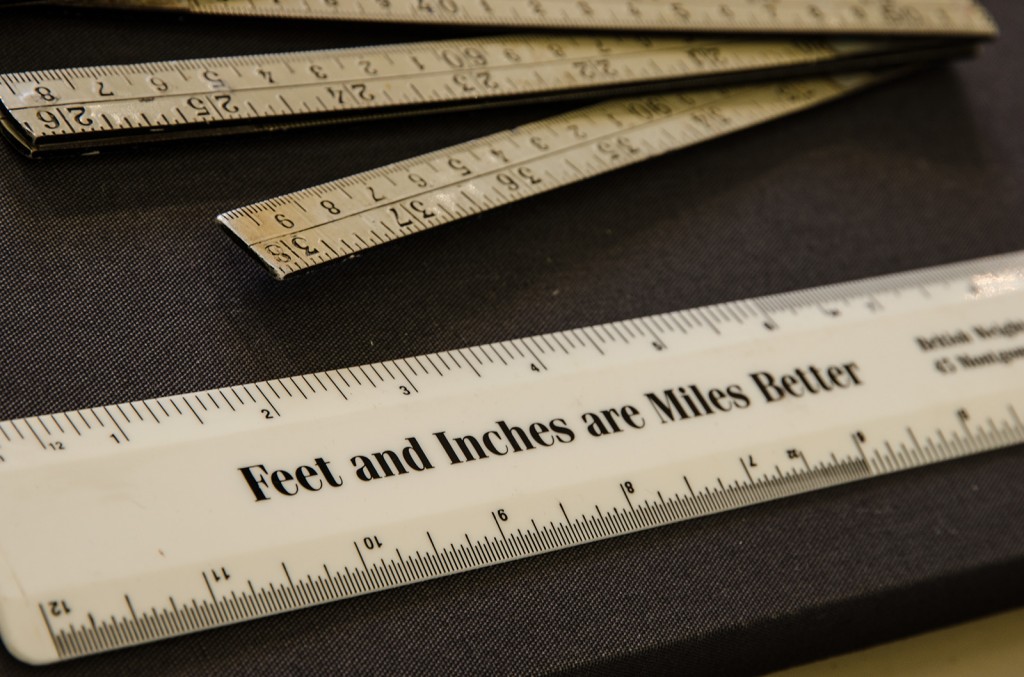

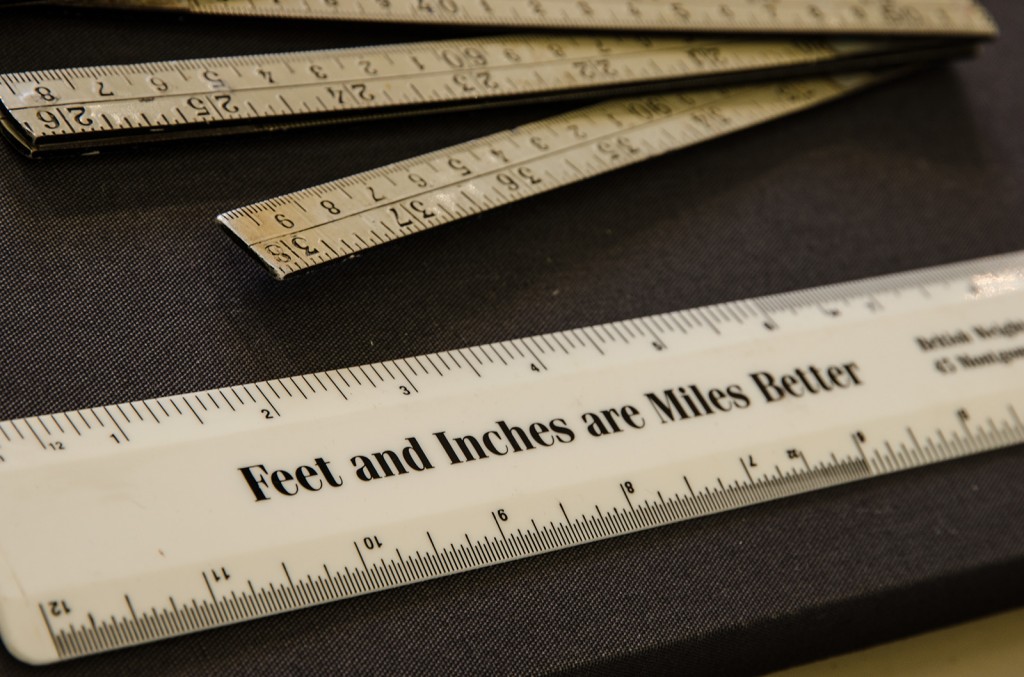

The final collection on show is a curiously pleasing one. It is a selection of rulers, measures and slide rules drawn from a larger set collected by Arthur Whillock (1912-2006), a hydraulics engineer at the Government’s Hydraulics Research Station near Oxford.

Mr Whillock was a founder of the British Weights and Measurements Association, which promotes the value of imperial measures and campaigns against compulsory metrication. He was also an officer of the Dozenal Society of Great Britain, which advocates the use of a base twelve number system over decimal’s base ten.

The collection was used by Mr Whillock in public displays to illustrate the view that “All naturally developed systems from ancient Crete to modern Japan have a spacing of about one foot as a basic unit […] Divisibility by twelve allows a wide range of proportions to be selected.” Now that is hoarding with intent.

Rulers from the collection of Arthur Whillock (1912-2006), inv. 13436

Complete object list

Presented by Mrs Christine Rhodes in 2011

Collection of Rulers and Measures, Mostly 19th and 20th Centuries, inv. 13436

Presented by Headington School, Oxford, in 2011

Large Dial Ammeter, by Electric Construction Company, Wolverhampton, ?1960s, inv. 13408

Large Dial Voltmeter, by Electric Construction Company, Wolverhampton, ?1960s, inv. 13409

Standard Cell, with Certificate, by Muirhead & Co., Beckenham, 1963, inv. 13421

Thermopile Heat Detector, by Philip Harris & Co., Birmingham, ?Mid 20th Century, inv. 13407

Geissler Tube with Yellow Residue, ?20th Century, inv. 13410

Transferred from the Department of Engineering Science, Oxford, in 2010

Recording Micro-Barograph, by Short & Mason for E. R. Watts, London, c.1902, inv. 13423

Gyroscope, by Newton & Co., London, c.1905, inv. 13293

Trotter Pattern Portable Photometer, by Everett Edgcumbe, c.1910, inv. 13422

On Sunday 18 August we had the pleasure of hosting professional freelance taxidermist Derek Frampton at the Museum. Derek delivered a very popular illustrated Table Talk on the Art and Science of Taxidermy.

On Sunday 18 August we had the pleasure of hosting professional freelance taxidermist Derek Frampton at the Museum. Derek delivered a very popular illustrated Table Talk on the Art and Science of Taxidermy.