Christmas has come early for MHS!

We have written before about the different ways that new items come into the Museum’s permanent collection – through auctions, donations and other routes. An important source of new material is that given by private donors, and the Museum has been fortunate to receive two recent donations in this way.

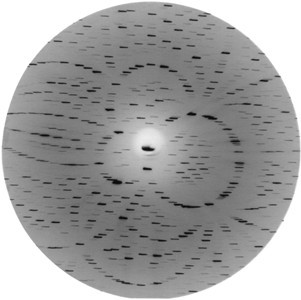

Single Plate Universal Astrolabe, European, 15th Century with Later Additions (inv. 14645)

A medieval European astrolabe, pictured above and to the right, was given anonymously and will be added to the existing collection of astrolabes which is already the largest and most important in the world. So why add yet another astrolabe to the collection? Is it just a specialist desire to complete the set?

Astrolabes are fascinating ancient devices which capture the apparent movements of the sun and stars in the sky. They were used in astronomy, time-telling, astrology and religion across cultures, time and places. But the latest arrival is an unusual design which the Museum does not have. It includes a universal plate for use anywhere on Earth, providing important new evidence of the transmission of advanced Islamic innovations to 15th-century Europe.

More than that, this new acquisition is an example of a medieval device that has been adapted and reworked in the 16th century: it tells a story of the Renaissance recycling rather than rejecting the Middle Ages. So yes, there is something of the completing-the-set mentality in our excitement at its arrival.

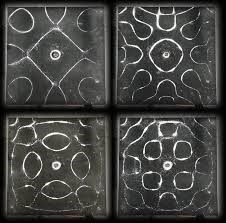

A second recent donation helps tell the story of the development of Elliott Brothers, an innovative British firm founded in the mid-19th century, and with origins in the late 18th century. The company produced instruments for navigation, surveying, calculating, telegraphy, optics, and mechanical and electrical engineering, for clients including the British Admiralty and War Office and the East India Company.

Material from the early production at Elliott Brothers has been painstakingly assembled over a number of years by Mr Ron Bristow, a retired engineer and manager with the business. Although the Museum already holds material from the company in its Elliott Collection, Ron Bristow’s items complement this by revealing more about the early stages of the business, as he explains:

The Elliott Brothers company collection, now in the Museum, had no items from before about 1850, even though the business began in about 1804. So I wondered what they did and what they made in those years.

Mr Ron Bristow with Museum director Dr Silke Ackermann

Using addresses traced by Dr Gloria Clifton in the Directory of British Scientific Instrument Makers, 1550-1851, Ron Bristow began to seek out early Elliott Brothers material, acquiring items from antiques fairs, friendly dealers, and auctions. After collecting objects from most of the early company addresses identified in the Directory, Ron decided that the material should remain together as a collection in its own right:

I always had in mind that the examples I had found should remain as a single collection and I am very pleased that the Museum of the History of Science is able to accept it in a safe and accessible way, where it will complement the company collection of later material.

Although many of the mathematical and drawing instruments in the Bristow Collection are quite standard, they offer examples of instruments made by several generations of a single craft dynasty. This illustrates developments in design and manufacturing style or technique, as well as the transmission of skills, first from craftsman to craftsman, and then to the skilled workforce of the larger company.

Both the astrolabe and the 28 items in the Bristow Collection will be accessioned to the Museum’s permanent collection, which continues to grow year by year. Excitingly, the Museum is also in the process of organising a new exhibition in the entrance gallery opening on 19 January 2016. This will allow for the display of these wonderful new acquisitions, and demonstrate the continued vitality of collecting in the modern museum, and the donations, grants and benefactors that make it possible.

There will also be two evening events in February and March to celebrate these objects. On Tuesday 9 February we will be hosting, Beyond the Archive, a conversation illuminating the back story the Bristow Collection with the donor, Ron Bristow. On Tuesday 8 March Dr Stephen Johnston will present the first research results on the European astrolabe, and its relationship to Renaissance recycling in Recycling the Astrolabe. You can book a free ticket to these events through our Eventbrite page here.