By Elizabeth Bruton

On Monday 10 February 2014, I attended the Historypin and Putting Art on the Map event at the British Postal Museum and Archive at Mount Pleasant in London. The aim of the event was to “crowdsource” expertise and knowledge in order to improve catalogue information about First World War art held by the Imperial War Museum, London. The particular theme of the event was Postal communications and Telecommunications in the First World War and further information about the event is available on the HistoryPin blog as well as the British Postal Museum & Archive blog.

All of the participants were given physical and online copies of a selection of art relating to World War One telecommunication and postal communications from the IWM collection and asked to discuss and contribute further details. While it was possible to contribute research and knowledge to multiple images (and this was something which happened more in the discussion at the tail end of the event), I choose to research a single image: Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps Signallers, Base Hill, Rouen : Telephones. Forewoman Milnes and Captain Pope.

Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps Signallers, Base Hill, Rouen : Telephones. Forewoman Milnes and Captain Pope. Art.IWM ART 2900. Copyright IWM.

The existing information in the catalogue was the title (above); the name of the painter, Beatrice Lithiby (OBE); and the description: view of a military telephone exchange, with four women operators seated at their telephone sets, a seated male officer and a soldier using a handset.

I began with the location, Rouen, France, and was able to discover the following information:

Rouen was one of the major Infantry Base Depots (IBD) and was in use for the duration of the war. Rouen in particular was a supply base and also home to a number of hospitals. As a result, it is home to a number of World War One cemeteries for the soldiers who died at the nearby hospitals. An IBD was one of the British Army holding camps which were situated within easy distance of one the Channel ports. IBDs received men on arrival from England and kept them in training while they awaiting posting to a unit at the front; they were also used supply bases.

Source: The Long, Long Tail: The British Army in the Great War of 1914-1918 – The Infantry Base Depots.

Information about Rouen base is available via the War Diaries held by the National Archives, in particular WO 95/4043 – Rouen Base: Commandant, August 1914 to December 1918. Unfortunately, none of these diaries have been digitised as of now (February 2014) in the National Archives Unit War Diaries.

Update from David Underdown at National Archives: At present [February 2014] only war diaries of divisions and subordinate formations have been digitised. GHQ, Army, Corps and Lines of Communication units have not yet been done (and nothing outside France and Flanders).

Next, I moved onto information about the artist, Beatrice Ethel Lithiby.

Beatrice Ethel Lithiby (1889-1966) Lithiby was a painter and designer born in Richmond, Surrey in 1889, the daughter of a barrister. She studied at the Royal Academy Schools and served as a war artist in World War One. On the death of her father set up her studio at Wantage.

Source: Suffolk Painters: LITHIBY, Beatrice Ethel (1889 – 1966).

Five of her paintings (none from World War One) are available at BBC Your Paintings: Beatrice Ethel Lithiby Lithiby also served in World War Two, in the Auxiliary Territorial Service and was awarded an OBE/MBE in 1944.

Next, I moved onto information about Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps.

Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps (QMAAC) was the successor (renamed) to the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC) and was given this title in April 1918 although it took a while for the title to be put to use. If the title is correct, then this painting is from late in the war, mid-1918 or afterwards. After a German air raid in September 1940, most of the service records of the QMAAC were destroyed. Surviving records have recently been digitised by the National Archives and are searchable online via the National Archives

The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was formed following Lieutenant General H M Lawson’s report of 16 January 1917 which recommended employing women in the army in France. Mrs Chalmers Watson became Chief Controller of the new organisation and recruiting began in March 1917, although the Army Council Instruction no 1069 of 1917 which formally established the WAAC was not issued until 7 July 1917.

Although it was a uniformed service, there were no military ranks in the WAAC; instead of officers and other ranks, it was made up of ‘officials’ and ‘members’. Officials were divided into ‘controllers’ and ‘administrators’, members were ‘subordinate officials’, ‘forewomen’ and ‘workers’. The WAAC was organised in four sections: Cookery, Mechanical, Clerical and Miscellaneous; nursing services were discharged by the separate Voluntary Aid Detachments, although eventually an auxiliary corps of the Royal Army Medical Corps was set up to provide medical services for the WAAC.

In appreciation of its good services, it was announced on 9 April 1918 that the WAAC was to be re-named ‘Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps’ (QMAAC), with Her Majesty as Commander-in-Chief of the Corps. At its height in November 1918, the strength of the QMAAC was more than 40,000 women, although nearly 10,000 women employed on Royal Flying Corps air stations had transferred to the Women’s Royal Air Force on its formation in April 1918. Approximately, a total of 57,000 women served with the WAAC and QMAAC during the First World War. Demobilisation commenced following the Armistice in November 1918 and on 1 May 1920 the QMAAC ceased to exist, although a small unit remained with the Graves Registrations Commission at St Pol until September 1921.

Further information on the WAAC can be found in Arthur Marwick, Women at War, 1914-1918 (London, 1977).

The first WAACs moved to France on 31 March 1917. By early 1918, some 6,000 WAACs were there. It was officially renamed the QMAAC in April 1918 but this title was not generally adopted and the WAACs stayed WAACs. The organisation of the WAAC mirrored the military model: their officers (called Controllers and Administrators rather than Commissioned Officers, titles jealously protected) messed separately from the other ranks. The WAAC equivalent of an NCO was a Forewoman, the private a Worker. The women were largely employed on unglamorous tasks on the lines of communication: cooking and catering, storekeeping, clerical work, telephony and administration, printing, motor vehicle maintenance. A large detachment of WAACs worked for the American Expeditionary Force and was an independent body under their own Chief Controller. WAAC/QMAAC was formally under the control of the War Office and was a part of the British Army.

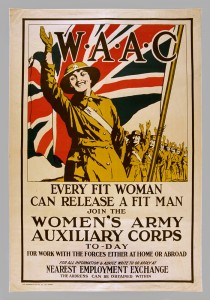

‘W.A.A.C. Every Fit Woman Can Release a Fit Man’, 1918 (c). Image courtesy of National Army Museum.

Based on recruitment posters depicting the uniforms of the WAAC and the QMAAC, it would appear that the uniform did not change when the corps name changed – see National Army Museum: ‘W.A.A.C. Every Fit Woman Can Release a Fit Man’, 1918 for an image of the WAAC and Art.IWM PST 13167: Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps, June 1918 for an image of the QMAAC uniform (thank you, Helen Glew!). Independent of the fact that this artwork does not show the front of the women’s uniforms, this lack of difference in uniform means confirming whether this artwork depicts the WAAC or the QMAAC is challenging.

Last and most definitely not least, I moved onto the image itself and was even to trace the details of one of the women depicted, Forewoman (Evelyn) Milnes.

Members of QMAAC served with Royal Engineers Signals and Postal Units and this is what this image appears to show.

The women are wearing the white and blue signallers armbands and are working as telephone operators. In civilian life up to and including World War One, most telephone operators were female. However, military telephone operators especially those in France, were generally men and Royal Engineers. For example, see the photograph below (which is also used in our header image).

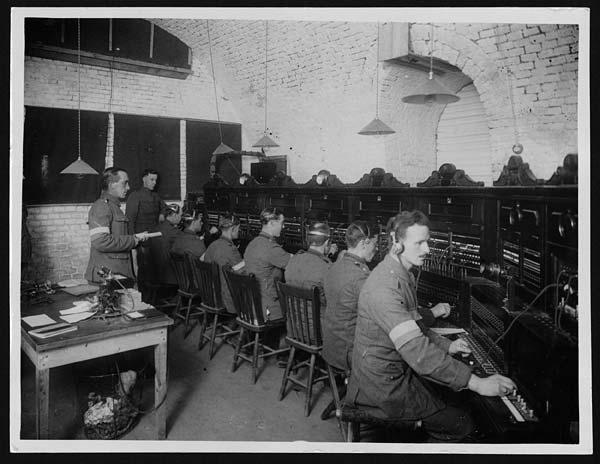

Signallers working at the headquarters of R.E.S.S. in France, during World War I. Image courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

The photographic image above entitled “Signallers working at the headquarters of the Royal Engineers Signal Service (RESS) in France during World War I” closely matches the setup and apparatus of this painting. This would suggest that military telephone exchange apparatus did not change significantly during the war, assuming the dates I have attributed are correct. Although undated, I would date the RESS HQ photograph image to c.1916 and assuming the artwork title is correct and this does depict the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps then this art can be dated to mid- to late-1918. The close match of apparatus and setup, even down to the lampshades and headsets used, also suggests that the war artist was realistically and faithfully depicting the telephone exchange and indeed may have based it on sketches taken in situ.

Later in the war, the gender of military telephone operators began to change and safer locations such as the telephone exchange at Rouen depot began to be operated by female operators. The US Army also used female telephone operators, in particular bilingual operators fluent in English and French, towards the later stages of the war. These were known, as they had been referred to at home, as “hello girls”.

The image shows Forewoman Milnes (WAAC/QMAAC equivalent of NCO), the lead female telephone operator (on the right of the image) and Captain Pope (the seated military officer). An additional second male soldier operating a telephone handset is unidentified.

Forewoman Evelyn Milnes

According to her military record held by the National Archives, Forewoman Milnes was Evelyn Milnes, born in Sheffield on 24 August 1881 and served in the WAAC and later QMAAC from 1917 to 1920. Evelyn Milnes had five years worth of experience in telephony when she joined the WAAC in 1917 having joined the Post Office as a telephonist in Sheffield in 1912. See Post Office: Staff nomination and appointment, 1831-1969. British Postal Museum and Archive POST 58 reference number 109, accessed via Ancestry.co.uk. Milnes’ appointment is referred to in Minute E23103.

Unfortunately, I’ve been unable to find information on Captain Pope (most probably Royal Engineers).

Further information about the telephone switchboards was provided by David Hay of BT Archives:

The telephone switchboards, or at least the cabinets, appear very similar to those used by the National Telephone Company seen at http://www.allposters.co.uk/-sp/The-Switchboard-of-the-National-Telephone-Company-United-Kingdom-Posters_i1874235_.htm, which is interesting as the NTC was nationalised in 1912 which would make these fairly old, presumably sourced by Royal Signals some years before. Post Office switchboards at this time were less decorative.

All in all, it was a wonderful, collaborative day and I look forward to contributing further information to the IWM art collection catalogue.

Dr Elizabeth Bruton is postdoctoral researcher for “Innovating in Combat”. See her Academia.edu profile for further details.