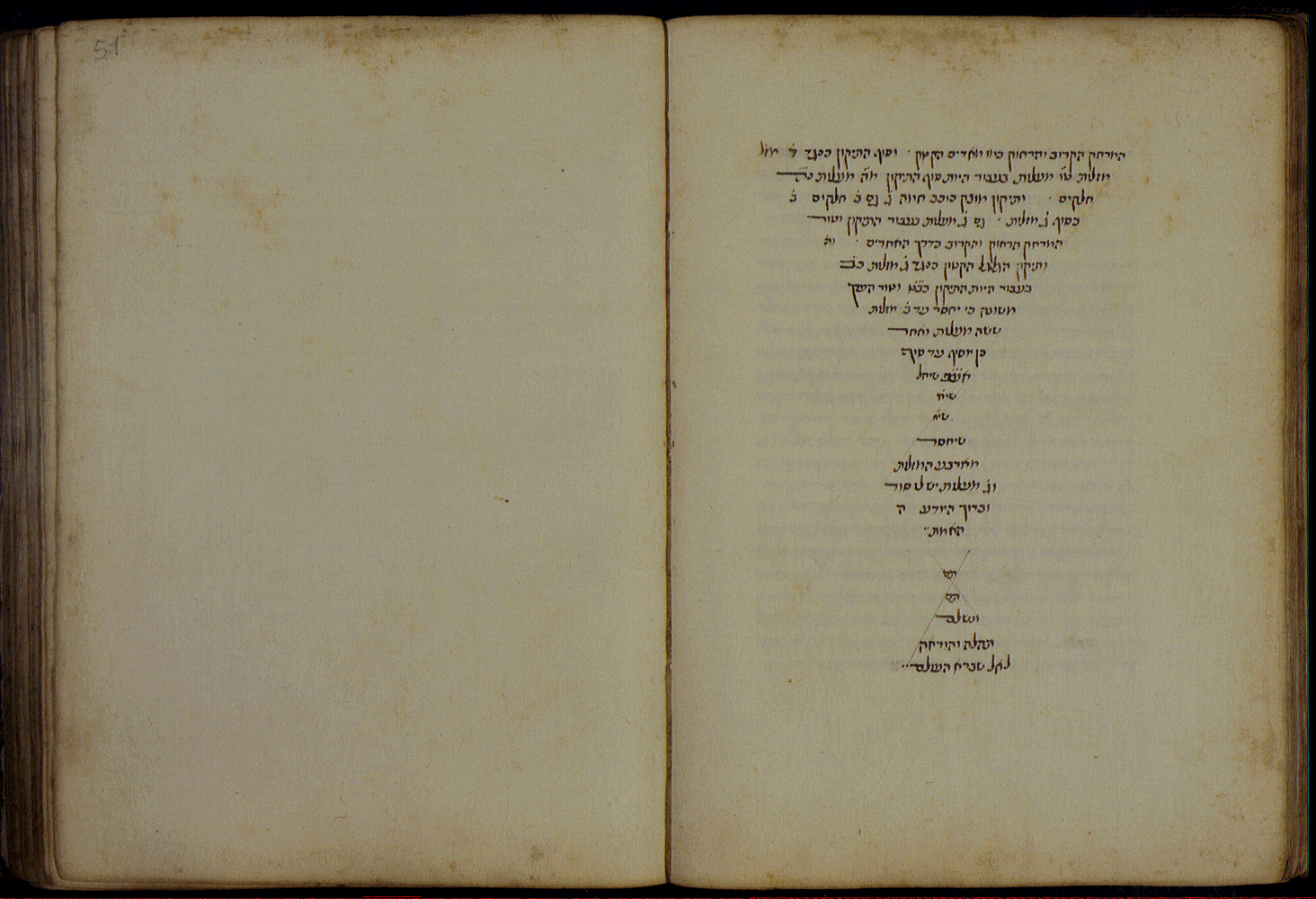

Ma’aseh kli ha-habatah, attributed to Ptolemy, Comunità ebraica di Mantova, 15th century.

Ma’aseh kli ha-habatah, attributed to Ptolemy, Comunità ebraica di Mantova, 15th century.

The research project ‘Astrolabes in medieval Jewish society’ has now been running for more than two years and has already proved to be a ground breaking and exciting research with active presence in several international scientific meetings and several publications on their way. The strength of this project was and is to approach two kinds of fascinating and complex medieval objects: Jewish astrolabes and Jewish manuscripts on astrolabes. For any outsider these two objects look materially disparate, but they are clearly approachable in several aspects. First of all they are the product of the medieval mind in the fields of astronomy, cosmology, and metal work. Astrolabes are scientific instruments and medieval manuscripts describe how to make and how to use them, so the strategy of the project is to compare the extant Jewish astrolabes to what is said about these astronomical instruments in the extant Hebrew manuscripts. This comparison should provide us with information about both astronomical knowledge and metal craftsmanship among Jews, the two skills that were essential to make functional astrolabes. Our second (but by no means secondary) task is to use all the data we can extract from manuscripts and instruments to build a general picture of how and why medieval Jews became interested in astrolabes and the contexts in which they used them and wrote about them.

There are about twenty astrolabes with Hebrew script written on them, a clear sign that Jews used them at some point. These instruments are all western astrolabes, i.e. they were made in Europe and northern Africa. Some of them are European (Latin script with additions in Hebrew), some are Islamic astrolabes from Islamic Spain and Sicily (Arabic script with Hebrew additions), and just a few are completely Jewish (Hebrew and Judaeo-Arabic scripts). They are multicultural and, often, bilingual, or even trilingual, as medieval Jews frequently were. None of these instruments has a clear history (they are mostly unsigned and undated). It seems that a few of them were made by Jews, but all of them were in the hands of Jews at some moment and their Jewish owners or users wanted to leave in the object a clear indication of its Jewish relation. Frequently, the Jewish input is confined to the names of the months and the signs of the zodiac engraved on the back of the astrolabe and on the rete, or the names of some city and the number of latitude inscribed in Hebrew on some of the plates. The oldest astrolabe in our research is a western Islamic astrolabe from the twelfth century that was made in al-Andalus. However, the Hebrew script was engraved later, we do not know when or where. The same applies to most of the Jewish extant astrolabes.

From the mixture of scripts, geographical backgrounds, and disparate owners and makers a question arises regarding these objects: on what basis can we label these instruments as Jewish? We are dealing with scientific knowledge, local art, cultural traditions (which are also religious traditions), and ultimately with national cultures and identities. The definition of Jewish was as complex in Middle Ages as it can be today. Jewish astrolabes raise questions amongst historians of art and science concerning the interface of the three major cultures of Middle Ages (Judaism, Christendom, and Islam) and the customary role of medieval Jews as merely intermediaries between the East and the West. If we look at the manuscripts (about one hundred in Hebrew and a few in Judaeo-Arabic, Castilian, and Judaeo-Spanish) the information they provide is richer and broader. Here we have names, but also descriptions, signatures, sources, and dates. We read manuscripts written and copied by Jews and for Jews throughout eight centuries and find ourselves in the heart of a living culture that was Jewish and felt Jewish. These hand-written texts somehow disambiguate the puzzlement that the instruments display in relation to their identification as Jewish cultural objects.

The oldest manuscript is mid-thirteenth century, but the history of the astrolabe in Hebrew literature starts earlier, in the twelfth century in Provence, in connection with the emigration of Jews from the Iberian Peninsula, and maybe earlier: a Judaeo-Arabic fragment from the Cairo Genizah might be the oldest testimony of the use of astrolabes in Jewish culture. There are original texts and translations into Hebrew of treatises on the astrolabe written in Arabic and Latin. The manuscripts come from all around the world, for they were copied from the twelfth century until the nineteenth in Benevento, Mantua, Syracuse, Vienna, Central Europe, Istanbul, Baghdad, Egypt, and Yemen, among many other places. The treatises have been copied not only with astronomical texts but also with astrological handbooks, monographs on geomancy, medical treatises, and books on talismans, which suggest that astrolabes were used not only in astronomical contexts, but also for astrology, medicine, and magic. The culture around the astrolabe was multilingual, multicultural, and multifaceted, and still Jewish.

Sometimes the researcher cannot avoid thinking in terms of a detective story. For instance: why would twelfth-century Jewish scientists care about astrolabes for the southern hemisphere when it was commonly accepted that the inhabited lands were all placed in the northern hemisphere? Why would an unknown hand have crossed out the names of the zodiac inscribed in Hebrew in the back on an Andalusian astrolabe in such a precise and specific way that the Hebrew characters could not be read? Jewish astrolabes certainly deserve a good novel, but for the moment they are the object of devoted and careful research at the Warburg Institute.